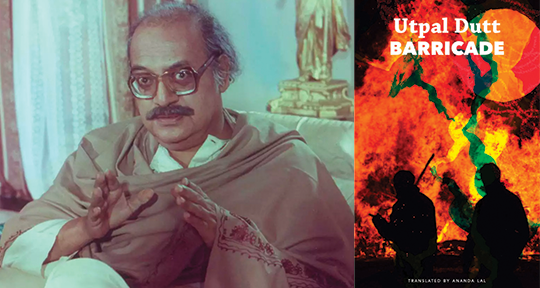

Barricade by Utpal Dutt, translated from the Bengali by Ananda Lal, Seagull Books, 2022

The Indian playwright Utpal Dutt wrote that myth is one of the most crucial forms of political storytelling because of its ability to transcend time and space, becoming relevant over and over again in new contexts. In Towards A Revolutionary Theatre, which is simultaneously a memoir of staging radical plays amidst the tense politics of his native Indian state of West Bengal in the 1960s and 1970s, and a manifesto about the necessity of leftist theatre, he cites William Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar as an example of a literary work that has “freed itself of the trappings of its own age and has become a gigantic myth,” continually reinventing itself for new political circumstances. This is seen in productions set in Benito Mussolini’s Italy, which form a critique of the tyranny, demagoguery, and mob rule that make such regimes possible.

Dutt’s play Barricade, which has been translated from the Bengali original by Indian theatre critic Ananda Lal and published by Seagull Books, is an attempt at such mythmaking. Set in the period just before the Nazi Party’s rise to power in Germany, the text is ostensibly about the party’s attempts to scapegoat their Communist rivals for the murder of an elderly political leader, but Dutt suggests throughout that the actual subject is the turbulent political situation then prevailing in West Bengal; the play was written in 1972, when the Congress-ruled government in Bengal was actively suppressing all forms of direct dissent.

However, as Lal said in a recent interview, “The fact that he set Barricade in 1933, when the Nazis rose to power in Germany, didn’t make his viewers think that it was remote from their lives. On the contrary, they connected with it viscerally, sympathised and cheered at the right moments.” This speaks to Barricade’s power as political myth, one which is increasingly relevant in the contemporary Indian context exactly fifty years after it was written, especially for its narration of how various democratic institutions such as elections, the judiciary, and the media are slowly co-opted and corrupted by the ruling party.

Dutt was highly influenced by Bertolt Brecht in his understanding of the political role of theatre, and the prologue uses a device similar to that used in The Caucasian Chalk Circle, in which a figure from the present day contextualises the play’s action for the audience, acting as a thread that weaves together two periods of time. Dutt uses the character of a Sutradhar (literally, a holder of the thread of the narrative, and of history itself) to set the story in motion by introducing the characters and interrogating them about their political views. The narrative of the play covers historically familiar terrain—the German elections of November 1932, subsequent political violence in which the Nazis attempted to blame their rivals, and the burning of books led by Joseph Goebbels outside Humboldt University in Berlin in May 1933—and is told through the perspectives of various characters who find their lives changed by these events.

Several of these characters are archetypal representations of various participants in democracy: the honest journalist who finds himself isolated in speaking truth to power; the corrupted editor who controls and twists the truth to serve the Nazi party’s needs; the Nazi official who parrots the party line; the judge who attempts to check executive powers while, in Lal’s opinion, apparently remaining politically impartial; and the politically detached intellectual whose conscience is eventually stirred by the burning of books. As a reader living in India in 2022, I found innumerable points of overlap between Barricade and recent events that have catalysed a similar political situation in India.

However, in his attempt at creating a political myth, Dutt does not lose sight of his characters’ humanity. One especially compelling portrayal, described by Lal as one of the most complex in the play, is that of the political awakening of the slain leader’s widow Ingeborg Zauritz, whose earlier belief in the sanctity of life and aversion to any form of politics are slowly eroded by her growing conviction that, with the scapegoating of enemies and numerous politically biased arrests—including that of her own son Paul—“to die standing up is better than to survive kneeling down […] the entire country’s a jailhouse.”

A fundamental part of Brecht’s idea of epic theatre was the role of the audience in Ko-fabulieren, or co-authoring the drama and bringing it to life. Dutt too saw the audience as “the link between life and theatre,” bringing their own experiences to bear on how the drama plays out. This element is apparent in the staging and linguistic style of Barricade; the contemporary cultural commentator Rustom Bharucha was “stunned” by the “memorable theatrical effects” in the play, which were deliberately expansive and detailed, and exemplified Dutt’s deliberate rejection of the minimalist and abstract ideas of the Indian avant-garde. Dutt saw such works as a “counter-revolutionary” attempt by the ruling classes to “drown the masses in a flood of abstruse books and plays,” rather than spotlighting works that spoke directly to their situation. To quote the translator’s note, Dutt “staunchly believed in the people’s idiom.”

Translating this idiom brought its own challenges, as Lal explains. In translating a play—especially one like Barricade, which was deliberately written in demotic Bengali—the spoken word needs to be valued over the written. Lal’s translation preserves the oratory element of the text; he even used a VHS tape of a production of the play as an additional source for the translation, apart from the published Bengali text.

The fact of Barricade being a play written in Bengali about people in Germany meant that Lal also had to make some specific linguistic choices. Dutt incorporated lines of German dialogue that were not always glossed on stage, contrary to the erstwhile practice, and Lal has chosen to translate these in footnotes rather than in the text. In keeping with the play’s underlying motive of commentary on the Indian political context, Lal has also preserved the use of colloquial Indian terms like sahib, baksheesh or radio-wallah in the dialogue.

While the political issues surrounding translation are more often caught up in issues of language and region than ideologies, texts such as Barricade present a specific set of challenges to the translator. Dutt himself was an atypical Communist, often deviating from the party’s line at the time. Unlike many others in the Communist Party of India (Marxist), he supported the 1967 peasant uprising in Naxalbari, and faced criticism for his supposedly reactionary work in the Bollywood film industry—where he acted in over a hundred films, including Satyajit Ray’s Agantuk and The Guru from Merchant Ivory Productions. Barricade was criticised by Communist publications for its portrayal of German party workers smoking and drinking, which went against the Indian Communists’ ideas of moral purity as heroism. A Marxist theatre weekly, amusingly missing the point of the play, exhorted Dutt to follow the Sutradhar’s instructions to “think of your own story, worry about your own homeland.”

Despite these criticisms, Barricade retains inherently Communist undertones, which inevitably complicates the question of whether a translation can remain faithful to this ideology. Lal has said in an interview that while he is not a Marxist, certain parts of Marxist ideology appeal to him, and “I believe in human values, so I will appreciate any work that offers these to me. I will not join in flying the red banner as at the end of Barricade, but that dramatic action in itself will not make me write off the play as ‘not to be translated.’ […] To me, Dutt held liberal humanist values above doctrinaire policies, and I find that stays constant in his best plays.”

This raises interesting questions about whether, in general, Dutt’s ideal political play can in fact become an auto-reinventing myth, one which is relevant in situations wherein the underlying political ideologies do not extrapolate fully. However, in the case of Barricade, its mythical quality outweighs differences in ideologies and time, and its message about the role of political apathy in the slow rise of fascism comes through clearly in the translation.

In terms of form, Barricade is not an outstanding play; there are no profound revelations other than what hindsight and an understanding of contemporary politics can give us, there are few hard-hitting or memorable dialogues, and some characters are at times so archetypal as to feel hackneyed, in spite of Dutt’s best attempts to humanise them. However, Dutt himself wrote in Towards A Revolutionary Theatre that he preferred his political plays to be critiqued for their ideas rather than their formal or aesthetic merit.

The power of the play lies in its ability to tell us what we, as readers, already know—that Adolf Hitler would come to power in Germany with devastating consequences for democracy, that the Congress party in West Bengal was similarly eroding democracy through its crackdown on civil liberties, that the present-day polity in India bears remarkable similarities to that described in the play, and that at every point in time, resistance remains the role of the intelligentsia, the media, and citizens. Lal’s translation highlights the fact that, regardless of Dutt’s own political views, his play remains relevant even fifty years on, and its prescience about the current political scenario makes its translation imperative.

Matilde Ribeiro is a law student based in Bangalore, India. She is a copyeditor at Asymptote, and has contributed to the blog.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: