This month, the Asymptote Book Club is proud to present Senka Marić’s Body Kintsugi, a moving and lyrical documentation through a woman’s interrogation of her own body as it undergoes disease, fracturing, and metamorphosis. Tracing the lineage of her physical fracturing through a fight with cancer, Marić reconstitutes the ideas of bodily fault lines and ruptures to conceive of a new wholeness, addressing the rifts and traumas of life to incorporate loss as an essential fact of survival.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

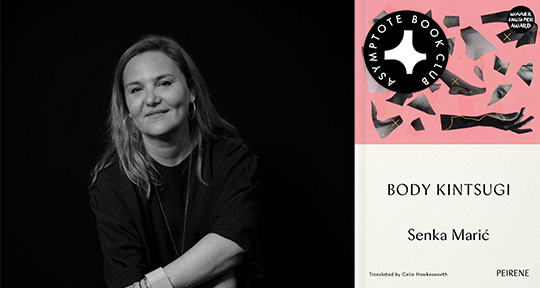

Body Kintsugi by Senka Marić, translated from the Bosnian by Celia Hawkesworth, Peirene Press, 2022

We don’t like to think of ourselves as a collection of fragments, but it is in our nature, as humans, to be cleaved into pieces by time and death—into “corpses strewn over the pages of history,” with nothing but the remnants of stories to tell of our struggles and victories.

Out of this nature of fragmentation arises Body Kintsugi by Senka Marić, a daring, visceral meditation on the female body and its reckoning with loss, fear, and mortality. A “story about the body” and “its struggle to feel whole while reality shatters it into fragments,” the book centers on Marić’s experience with breast cancer, a vehicle by which she uses to explore self-perception, self-preservation, and relationships. Although Marić begins with her singular, personal history, her discursive space gives birth to an ambiguous “you”; the narrative quickly evolves into a discourse on the collective reality of shreds and patches, enticing a metaphysical reconciliation of impermanence—our own and of those closest to us.

The protagonist’s rupture begins with the loss of her husband to adultery, followed by a more visceral loss: that of one breast, then the other, and finally her hair and life force through the traumatic process of chemotherapy. Although the protagonist loses her former self piece by piece, she comes to reassemble it through surgery, treatment, and radical acceptance, focusing not on the disease itself, but what remains in lieu of it. This theme blossoms to take hold of the entire text—that of physical and spiritual kintsugi.

Kintsugi refers to the Japanese technique of reassembling broken ceramics with liquid gold or platinum, leaving the cracks visible. With the intention of showcasing rather than hiding the object’s past, kintsugi honors the unique history of each artifact by emphasizing its damage and fracture, thereby bestowing upon it a renewed vitality and a more complex beauty. Like a delicately reconstituted piece of pottery, the human body suffers under the brutality of being taken apart and put back together, but goes on to redefine beauty in the context of its pain and brokenness. Though raised to believe that bodies are inherently flawed and that they should be fixed until they’re “good enough,” Marić iterates how wholeness and incompleteness are not antithetical. The series of autobiographical vignettes that make up Body Kintsugi explores this corporeal ceramics; for Marić, her body is a site of trauma and dismemberment, but also of healing, the ongoing nature of which she uses as a canvas to consider the relationship between the self and its surroundings. Through the lens of a personal memento mori and interludes of mythological mishmash that appear almost like the pinnacle of a postmodern conscience, Marić’s inquiries radiate inwards—the terribly painful impetus of a memoir mourning a body forever lost.

Just as the kintsugi mechanism seems to be an all-pervasive force in all the bodies of the world (islands as “remnants of the clay from which the gods formed the earth”), so have words always been “the thread with which emotion is stitched to reality.” Each chapter in Body Kintsugi, then, is carefully woven into a coherent whole, creating threads of thinking that outlast their own brevity, and leaving the reader to pour out the gold between the anecdotal pieces. In their vital account of the perpetual patching and rejection of a woman’s ever-changing body, Marić traces her years of hardship along a course of unpredictable therapies and incisions, the series of scattered alterations grinding her down to a nub—not necessarily the result of painful, toxic medication, but a consequence of her now “shattered body.” As a “woman without the body of a woman,” Marić sees herself as embodying the “darkness of blood never capable of finding peace.”

In parallel, she revisits old haunts, reflects and questions them, approaching without any reservations the mysteries in her past. In this attempt to unearth her family’s enduring narrative, the “body kintsugi” comes to equally refer to the way she renders her own life story from a harrowing girlhood and the equally tumultuous quandary that is her adulthood, building an unconscious mise-en-scène of her former selves pieced together by painful experiences—violence, disease, loss. Through the intimacies of this prose work, the reader experiences Marić’s longing for human touch, conjured up by the frequently recurring reminiscence of her grandad’s hand holding her foot or nestling into the body of a lover: “The woman in you is ready to be loved, in this body which itself chooses its shape, overcoming the borders that endeavour to reduce its perfection.” Dispensed with fiction, the writer appears to be eager to document everything: nipples, pimples, period blood, the list of body parts lost between her family members. In a dichotomy between the material and the ethereal, Marić’s writing keeps her anchored in her physical existence:

Last night you woke up writing a letter to your father who died nearly sixteen years ago. He was standing beside you, hazy and faint, out of focus, a silhouette losing its edge . . . You thought he couldn’t hear you, and that’s why you began to write. Or you began to write because it’s only when you write that you really think. Or because it’s only then you know you exist. You wrote black letters on white paper torn out of a small, lined exercise book: When I write, others really don’t exist. At best, they are functions. I write only to seize the moment. And myself in it.

The pared-down, simple style of Body Kintsugi is elegant and rich in detail, but also perfectly understated and almost clinical in its precision (and even literally clinical). Despite the simplicity of its form, Marić recognizes in this work the cathartic gravity of such issues, creating a raw, honest story without a trace of forced pathos—a story from which unfiltered life itself oozes forth in all its manifestations. Certain critics might find the homespun candor and lyricism of her corporeal experience a tad heavy, but rarely does one encounter writing that emanates from such a firm backbone of interiority as that within Body Kintsugi. The emotional turbulence through motherhood, sex, love, and loss is at times violent, yet also folds into tenderness, like an embrace from a sympathetic friend, a fellow traveler. An adept painter of vivid frustration, Marić applies a lagging, interruptive visual style to the real—and therefore perhaps anticlimactic narrative line, artfully navigating the at-times unanswerable, at-times hopeless matters of a life.

Marić’s style is also undoubtedly a translator’s dream—a captivating montage of perfectly timed comedic interludes and beautifully crafted flashback sequences, all wrapped up in short, free-flowing sentences. Celia Hawkesworth’s faithfully rendered dialogue is both gentle and powerful in equal measure, hitting the cultural nuances in all the right places and creating an accurate portrait of female adolescence and Balkan upbringing, both instantaneously evocative and poignant.

Through all that is quiet, delicate and unimposing, Marić has honored the vibrant, silent energy that the body contains, bringing it to the page in its truest form. Her strength and vitality in the face of struggle is anything but cliché: it is complicated, beautiful, and moving. Sometimes she moves to tears, sometimes to laughter, and sometimes she appalls in her descriptions of sinister violence. Her odyssey, which moves from the desire to be cured to the desire to merely persevere, comes full circle on the peninsula of Pelješac, cancer free and among the “blueness capable of singing” that swallows up the now-remembered pain, the sizzling sun gleaming off the golden crevices of a woman, who fought herself to be here.

Katarina Gadže is a writer, editor, and translator from Croatia. She studied English and French philology and translation studies at the University of Zadar and the Sorbonne, and now lives and works in the heart of Europe—Brussels.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: