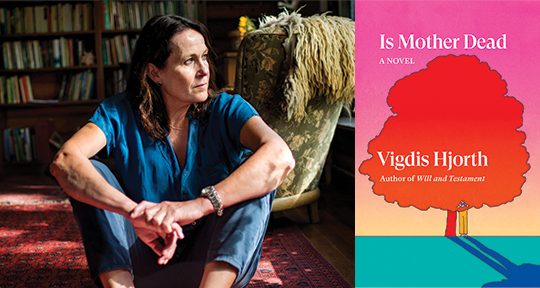

Is Mother Dead by Vigdis Hjorth, translated from the Norwegian by Charlotte Barslund, Verso Books, 2022

In a charming 2017 interview with the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art in Denmark, Norwegian writer Vigdis Hjorth sang the praises of Kierkegaard, quoting the proto-existentialist on life being a task and an adventure—the adventure just to be you, “every single day with great fervor and responsibility.” Her novels, over a dozen of them, instantiate this charge, with several following characters grappling with existential crises precipitated by a sense of alienation from their families, their past, and their own authentic selves.

Such a crisis breathes life into her latest novel, Is Mother Dead, out with Verso Books and translated by Charlotte Barslund. Joanna is the narrator and protagonist, a successful artist in her mid-sixties who is estranged from her family, which inevitably causes an estrangement from her past and—she wonders—her true self. Confronting her family—her mum and the woman’s role in affecting the formation of Joanna’s self in particular—becomes the task of Joanna’s art and her life, this adventure driving the novel.

What could cause a rift in a family so enduring that decades later, a daughter is forced to stake out her mum’s apartment just to confirm she isn’t dead? Writing with a rush of anxious interiority beautifully reproduced by Barslund’s translation, Hjorth spins out Joanna’s hopes, fears, and half-suppressed memories in obsessive and propulsive run-on sentences, full of self-reflexive questions and crushing doubt. Though Joanna’s “default setting” is feeling alone in the world, she is compelled to confront her mum to understand something deeper about herself—to consult her deepest self, because “. . . we all carry our mothers like a hole in our souls.” Her mum has no interest in such confrontations or consultations, and therein lies the conflict.

Joanna fled a conventional life and conventional husband in her early twenties, moving to America, abandoning her bourgeois parents and sister, and saddling them with what they consider unforgivable shame. When Joana fails to return home for her father’s funeral, the estrangement and bitterness set further, hardened as concrete. Aside from the occasional text from her sister about practical matters like inheritances, she hears nothing from them until she leaves Utah for Oslo. Returning to Norway after all these years out of a sense of untetheredness, with her son grown and moved away and her husband dead, something more has called for her presence. Her pretext is to produce new work for an upcoming exhibit, but Joanna—and readers of her story—quickly realize that she’s there to confront her mother. Joanna isn’t quite sure herself what she expects from her mum, but there’s a wound in her past that rankles, refusing to heal until it is exposed to air.

Her mum’s task—or perhaps the chief obstacle to what Joanna might recognize as a real task—seems to be a steadfast devotion to nursing the aforementioned slights, plus the public disgrace she felt when a local gallery showed Joanna’s work, which featured gloomy and incriminating paintings suggestively titled Child and Mother 1, Child and Mother 2. Joanna learns that her family was mortified by the work and its implications—a failing at the heart of an otherwise respectable family and a dark secret of Joanna’s work and life which, finally, upon her return to Norway, conspires to be revealed.

Will the wound heal? Joanna harbors hopes of meeting her mother:

. . . without being frightened or doubting, not proud of my success or vengeful, but completely humble and trusting, with the greatest devotion, and see Mum through the eyes of a child, a gaze that entrusts my entire destiny to her, the noise of the traffic would still, the rustling of the trees would cease, we would be surrounded by total silence and she would be unable to resist. Having the courage to do that.

Joanna is a mother and a widow; her mother is also a mother and a widow. Can’t their shared experiences and sources of grief help bring them together? Hasn’t time taken the sting out of their painful past? Doesn’t it teach us that we’re all culpable? Yet, her mother refuses to see Joanna, ignoring her calls, texts, and emails. Joanna, increasingly desperate to speak with her, increasingly either reckless or courageous or both, continues to track her mum, simultaneously investigating her own past, conjuring suppressed and heart-wrenching memories of her emotionally abusive father and confidences from her depressed, perhaps once even suicidal, mother: “The first song I ever heard was Mum crying by my cradle.”

There are two intertwined tasks at the center of Joanna’s undertaking: to confront her past by facing difficult memories, and to confront her mum in the present. The tension builds as readers wonder whether and how Joanna and her mum will face each other, as Joanna resorts to stalking her, hiding in bushes, following her to churches and graveyards, and sifting through her trash like a seedy private investigator. During this chase, more memories are revealed or resurface to intensify the stakes of the coming confrontation: a child’s drawings that came dangerously close to capturing and exhibiting some of these truths; scarred forearms; a cigar box buried in the yard under cover of night. Joanna’s compulsion to see her mother takes over, though she retains enough self-awareness to admit: “My brain isn’t in on this, my brain has abdicated.”

Similarly, she is not naïvely hopeful for some fairytale outcome, even if successful in her confrontation: “A fresh start wouldn’t be possible even if I could make her listen to and somehow acknowledge my story, we’re too old for that, but perhaps we could reach a kind of truce.”

What, then, is Joanna’s story?

Her father was verbally abusive, controlling, dismissive of her interest in art—dismissive of her. Her mum was often cold, distant. Young Joanna was starved for love and support. But this isn’t the whole story; a betrayal lurks somewhere, a trauma suppressed, glimpsed only in Joanna’s art and essential to its making, her art an extension of her project to be an authentic self. “Snatch the blindfold from your eyes,” Joanna exhorts herself, “paint your eyes open, paint their eyes open, it’s in your power!”

Perhaps this is the real reason Joanna’s mother refuses to see her: a fear of what Joanna will dig up, and what she’ll in turn be forced to face. On the surface, she has no desire to revisit the past or to aid Joanna’s quest to become whole, but there’s a thread connecting them beyond blood, a precious memory that only Joanna is privy to, wherein her mum was struggling, in pain, in touch with anxiety in a way that made her raw and real to Joanna: the “desperate Mum of my past,” the “. . . mute Mum whose silent screams I hear all the time.” This is the mother Joanna wants to, needs to, see. Joanna thinks that woman is still there, needing to be freed, and that in doing so Joanna will free her own deepest self. Armed with this conviction, she will not be stopped:

I can’t forget Mum because I suspect that her early ambiguous love for me and her current obstinate refusal to engage with me reflect her own unresolved conflicts, and I want to know more about them. Mum’s mystery is my mystery, it’s the enigma of my life, and it feels as if it’s only by getting closer to it that I can reach some kind of existential resolution.

Earlier in the aforementioned interview, Hjorth quotes another bit of Kierkegaard from memory: “So many people live in their own cellars, although the top floor is vacant with a spacious view and infinite perspective.” She ponders: “it makes you want to climb up there,” and that after reading the philosopher’s works, one feels a deeper sense of mattering. If we read the basement as suppressed memories, buried by pain and time, and the top floor as the land of fervent, authentic living, Joanna performs this double movement throughout the novel, the descent a prerequisite to the ascent. Is Mother Dead both pulls readers into Joanna’s adventure and calls on them to become more alive to their own task, their arms stretching upward for the next wrung.

Kent Kosack is a writer, editor, and educator based in Pittsburgh, PA. He serves as the director of the educational arm at Asymptote and his stories, essays, and reviews have been published in Tin House (Flash Fidelity), the Cincinnati Review, the Normal School, Full Stop, and elsewhere. See more at: www.kentkosack.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: