Michelangelo Antonioni and Julio Cortázar form our double feature for this latest edition of Asymptote at the Movies—a perfect pairing in their own idiosyncratic way, as two auteurs who both formidably challenged the responsibilities and capacities of their mediums. Cortázar’s “Les babas del diablo” was published in 1959, and a short six years later, Antonioni’s Blow-Up hit the theatres. Both works have at their centre a photographer: Cortázar’s narrator, Michel; and Antonioni’s protagonist, Thomas. Both also see their leading men stumble across something sinister, which drastically—and perhaps irreversibly—alter their engagement with their respective realities. Cortázar and Antonioni have both declaimed any other significant crossover between their works, and indeed they seem to have little more in common besides an overarching narrative catalyst. . . but isn’t there always more to be found when two intelligences are in dialogue? In the following roundtable, Chris Tănăsescu, Thuy Dinh, Xiao Yue Shan, and Rubén López discuss these two masterpieces, their phenomenology, and how the mode of translation works between them.

Chris Tănăsescu (CT): I read Cortázar’s story only after watching the movie—actually, after watching Blow-Up multiple times over the years. But I believe this is far from being the only reason why, when I did finally read the Cortázar text, it seemed to me that the story had been written after the movie, and not the movie that was based on—or rather, “inspired by”—the story . . . The story struck me as a piece I would have expected Antonioni to write himself. “This is Antonioni,” I thought to myself . . . His cinematic poetics, the style and language (of characters in various movies of his, quite a number of them writers or artists), even his obsessive motifs (such as composition versus/and/as the machine) were all there. What’s more, Cortázar’s speaker’s moody, stylistic, grammatical, translational, topographical, and voyeuristic flaneuring seemed like the perfect illustration [and at times even (re)wording] of some of Antonioni’s most well-known statements about the art of modern filmmaking; particularly the ones in which he ponders over the director’s mission to capture a never-static flux-like reality by continuously staying in motion and incessantly gravitating towards, and away from, moments of potential crystallization. The “arriving and moving on, as a new perception.”

Thuy Dinh (TD): I prefer to think that each work—whether the film or the story—exists independently of each other, with its own unique language and attributes, yet can converse with or sustain the other like a dance, a collaboration, or an equitable marriage: where no one has, or wishes, to have the upper hand. This idea of conversation seems more inclusive, and helps us to gain a more holistic view of what we call “reality,” don’t you think—especially since both Antonioni’s Blow-Up and Cortázar’s “Las babas del diablo” squarely address the limitations of subjectivity and/or the inherent instability of any narrative approach, and in so doing invite the audience/reader to accept the fluidity of all human experiences?

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): This concept of dialogic resonance operating inside the small words “inspired by” is so discombobulating and vast, it’s a shame that we only have the linear conceit of before and after to refer to it—but before and after it is. Chris, even though as you so precisely pointed out, the film is rife with Antonioni and his inquiries (that of the despair innate in sexual elation, that “memory offers no guarantees,” and that hallucinogenic quality of modern opulence), I think at the centre of his Blow-Up is this idea that life is always interrupted with seeing, and seeing always interrupted with life, and this is, I believe, a direct carry-over from Cortázar’s mesmerising, illusive tale of what it means when the gift of sight is led through the twisted chambers of seeing. Which is to say, I agree with both of you, that at the confluence of these two works lie a similar attention to fluidity.

Rubén López (RL): As a Spanish speaker, I have an obvious inclination to read Cortázar in his original language, which is a mixture of French and Spanish. To my mind there is also something that Antonioni’s character loses by being a British local. Cortázar’s protagonist is a Chilean-Frenchman living in exile; this theme of exiled characters is quite common in Boom and mid-twentieth century literature due to Latin American dictatorships. But my perception is that his dual status is more evocative than the gaze of a local. Even his search for street images has a sense of curious exploration of the unknown, perhaps a little less imperialistic. It also seems to me that the English Blow-Up robs the original title, “Las babas del diablo,” of much of its poetic force: a potent image of a figure that represents an extremely delicate object through a demonic figuration or, on the other hand, a brutal object through a virginal metaphor.

But something in which both characters coincide, both Cortázar’s and Antonioni’s, is in the dislocation of the narrating subject. Somehow the impossibility of narrating—of being this subject who has an absolute truth about the facts—implies the death of the author, as proposed by Barthes. There is no truth, no ultimate intentions in any text: only this strange eagerness, a blind insistence on life through the verb/image.

CT: I find the notion of translation really relevant, Rubén, particularly where you discuss the Spanish nuances and the literary and political background for the story. Cortázar’s Michel was a translator, and the translation he was working on speaks ironically to the plot—as well as to Antonioni’s moral concerns. Translation is at the same time, in both cases, intermedial and machinic: between photography and hypothetically mechanic writing in Cortázar, and between photography and moving image across (spoken) text and soundscape in Antonioni.

TD: In the case of Antonioni, while we could say that his film is a translation of Cortázar’s story, it is also a translation of a translation, correct? Antonioni, an Italian, decided to make a film about a British photographer living in London, which in turn was based loosely on a story by a French-Argentinian writer living in Paris and writing in Spanish. Did Antonioni expand or accommodate Cortázar’s story in his film adaptation? If we mainly focus our discussion on Antonioni’s filmic language, would we then treat his film as superior to Cortázar’s aesthetic concerns? Or is it more accurate to say that Antonioni, in his own way, also resolves/naturalizes the ruptures raised by Cortázar’s language? Can both the film and the story, while addressing different aesthetic issues, have comparable space in the discussion, even if we are “at the movies”?

RL: In that sense, Antonioni didn’t just adapt Cortázar’s work, he dialogued with it and created a synthesis of his aesthetic concerns and the text using his unique cinematographic language. Like the artist, Antonioni fixates on some elements of the short story (camera, photograph, voyeurism, heroic delusions) but hides the rest; many layers from Cortázar’s protagonist become an afterthought, as Antonioni’s anxieties are not fixated there. The type of translation the director performed is based on something that exceeds language to become a personal logos.

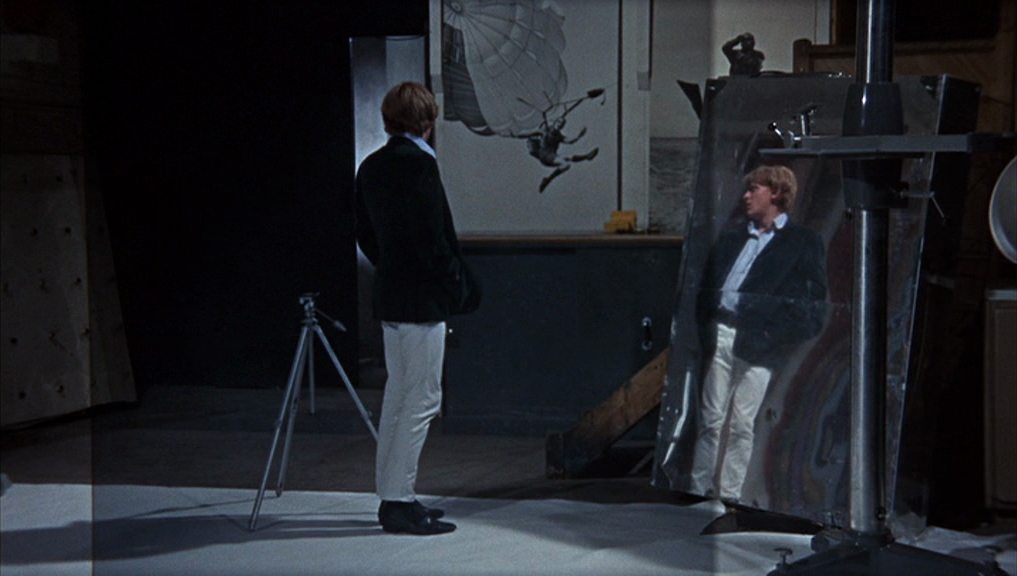

CT: I’d say Antonioni found the plot and theme of the story, and mainly the richly suggestive trope of blowing up photos, to be a serendipitous metaphor for what he was doing himself at the time. He had been in London for quite a while doing research for . . . making a movie about the age’s fervently emerging culture. He was therefore “blowing up pictures” trying to grasp the complex milieu, while still aware that he could not but remain a stranger and a foreigner. The world of photography and visual arts more generally particularly grabbed his attention as both prolific and working pervasively throughout the culture—although somewhat from behind the scenes. The movie’s degree of “reality” is therefore amazing (also tying in with Antonioni’s own background as a documentary filmmaker): Thomas’s pictures for his book project were taken by a well-known photographer of the time, Don McCullin; many of the interior scenes were shot in a real-life studio (belonging to Jon Cowan, who also offered his photographic murals to be featured in the movie); Thomas’s painter-neighbor Bill is a filmic version of painter Ian Stephenson whose paintings are featured as Bill’s and also decorating Thomas’s studio, and so on and so on.

There is huge irony in the way Antonioni keeps enlarging the image of the culture under his magnifying glass and “blowing up” his own “photographs” to ever larger proportions: in doing so, just like Thomas and Cortázar’s Michel, he keeps stumbling on black-and-white grim realities, mendacity, and injustice or corruption buried under the vividly colorful scenery. But there is huge self-irony too: again, like Thomas and Michel, he may have initially pictured himself as pointing to or uncovering something horrible (and perhaps preventing it from happening [again]). When he comes to the realization that he failed though, his failure preserves the tremendous scale of the attempt. The immensely detail-rich panorama amounts not only to ethical, but also inevitable gnoseological defeat: the closer he looks and the deeper he digs, the more he understands he cannot really understand. And then, isn’t that the viewer’s understanding, or feeling, too?

TD: Yes, I think so. To “blow up” is to enlarge an image so one can see clearer, yet this idea of enlargement can also be obliterating, being the opposite of a layered mystery. In an interview, Antonioni acknowledges his title is a misdirection, and in this sense he hews closer to Cortázar’s literary vision by defining the true image of reality as an “absolute, mysterious [nothingness],” itself being “the decomposition of any image, of any reality.”

Ultimately, both Antonioni’s cinematic approach and Cortázar’s literary vision are simply two sides of the same coin. Antonioni’s protagonist thinks he is preventing a murder from taking place, Cortázar thinks he intervenes a pedophile’s illegal solicitation of an underage boy. Both artists boldly address the limits of narrative, yet also liberate us from the shackles of tradition by showing us ways of deconstructing, and reframing/enlarging what we call reality. For example, Antonioni’s camera follows Thomas but also makes us see other realities, like the African nuns and South Asian residents of London walking on the streets, or the gay men near the antique store where Thomas buys his wood propeller. And both Antonioni and Cortázar also acknowledge that, unlike painting, photography allows the photographer subjectivity but not complete control, as unexpected background elements always threaten to disrupt his frame, like the pedophile’s car just outside of Michel’s frame in Cortázar’s story, or the hidden gun at Maryon Park in Antonioni’s film. Even objects like the propeller wing, or the smashed guitar that Thomas manages to grab from fans at the concert, don’t necessarily become meaningless outside of their “framed” contexts. These seemingly discordant notes are both essential to the film’s context and also as time-capsule objects—Antonioni, in seemingly recording the moment, wishes to project his panoramic “blow up” vision into the future, because the contemporary eye may not see everything that somehow finds its way into his frame. (In fact, Blow-Up initially bombed when it came out, and audience walked out of the film.) The fact that we are still talking about Antonioni and Cortázar means that their visions have escaped the confines of their time and space.

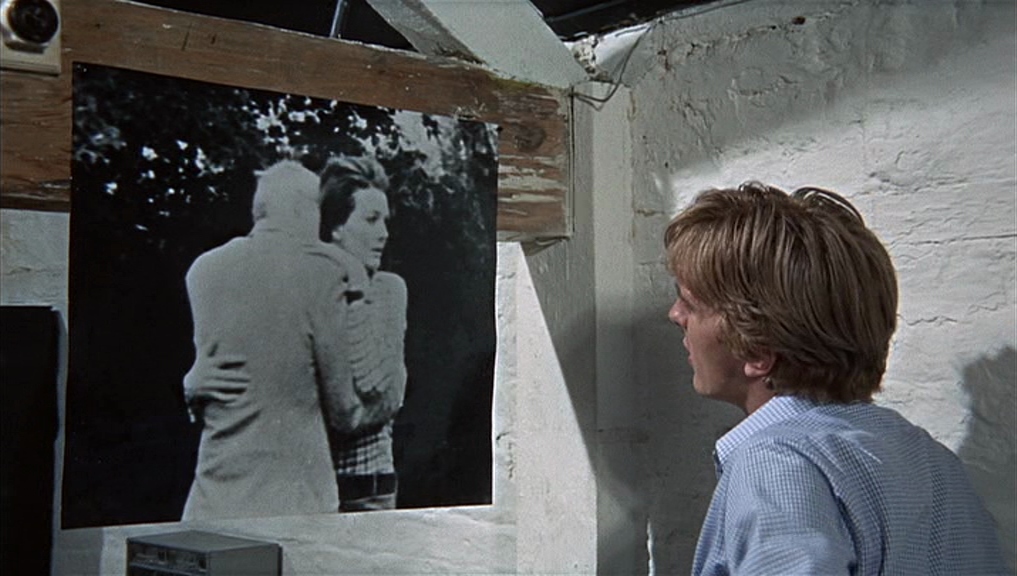

XYS: Cinema shows and text tells; the chasm between these two methods, as illustrated by these two artists, is in the negative capacities of both. When the text does not tell, it is because it is not thought. When the film does not show, it is because we are being directed to something other. Chris, you put it beautifully when you said that for Antonioni’s photographer, “his failure preserves the tremendous scale of the attempt.” I felt that same disarming sensation in Cortázar’s narrator, that his efforts to understand his photograph has somehow overwhelmed and swallowed up the true knowledge of it; he admits of himself: “I might be able to tell it in much greater detail but it’s not worth the trouble.” This carries over into Antonioni’s leading man, who is equally guilty of this indulgence. Those incredible photographs of poverty and desperation by Don McCullin represent a fascinating miscarriage of documentary responsibility, arranged and bound in a narrativization of suffering, in which its actual subjects have no agency. “The rest of [this] book is quite violent,” the photographer says, and implies that the supposedly lovely image of two lovers in a park would implant some saccharine happy ending.

It was a dream that the photorealistic image would relieve all the insidious burdens of language—that to show something as it is would somehow ameliorate that horrible dissonance (which I’m sure we’ve all felt) between language and its subject. But it just opened up a whole new world of questions, didn’t it? I loved that even though it can be said that the text has envy of the image, and the image has need of the text, both Cortázar and Antonioni’s portrayal of the photographer unloads onto photography all the discomforts of their own medium. Cortázar questions the still frame and its disembodied nature (how can a word be a representation), Antonioni questions the still frame and its predatory instincts (how to tell the truth with lies), and both question the image’s epistemology—what can it really know, what can it even tell us?

Cortázar wrote it so wonderfully when he said: “. . . a frozen memory, like any photo, where nothing is missing, not even, and especially, nothingness, the true solidifier of the scene.” We’ve talked some about the somethings present in the film and in the story; I’d like to know, what did you all think of the two works’ portrayals of nothing?

RL: For Cortázar the fantastic is so simple that it always happens in day-to-day reality. That is to say, underneath the apparent triviality there is fantasy: our reality is simply a mask that hides another layer that is neither transcendent nor philosophical, but profoundly human. I believe that the apparent nothingness is just our existential nakedness.

As much as both protagonists insist on their altruistic intentions, on a moral conviction about art as a transformative tool, their efforts turn out to be vain or ambiguous in the end. Particularly in the case of his protagonist. Ultimately, he imagines that he prevented a death with his lens in order to give meaning to his artistic exercise, so as not to lose himself in the absurdity of commercial photographs and to trust that his aesthetic conviction would have transformed the world. The same happens with Cortázar’s; he convinces himself that perhaps his art has prevented a crime against a minor, although it will probably be repeated the next day. Then, art as a tool for social transformation—something that movements like socialist realism attempted in the early twentieth century—becomes a somewhat empty object; as the piece of the broken guitar or the propeller, the art becomes merely trash or a commodity. Even the subjects become commodified for the gaze of the photographer.

CT: To me too it’s a media-based and mediated (mediating?) nothingness with, again, strong (sub)cultural and, as Xiao Yue puts it, epistemological implications: not only the photos, but photography itself looms larger and larger. By engulfing everything (and actually . . . nothing) and becoming nearly ubiquitous, photography also becomes invisible (just like the translator, in Laurence Venuti’s terms, right?) and, quite likely, pointless (“I didn’t know the reason, the reason why . . .” persists Cortázar’s speaker). The issue of time—“time-capsules,” felicitously says Thuy (isn’t any arguably relevant literary or artistic work a potential time-capsule?)—and, moreover, temporality, presents itself as a closely related concern. In Cortázar it comes along with the modern(ist) tradition of non-linear storytelling and parallel plots and chronologies while nevertheless voicing his own unique vision and style, and is, therefore, the nothingness of the “now” in which the speaker is confronted with his own failure (“I understood, if that was to understand [. . .] [that] which had not happened, but which was now going to happen, now was going to be fulfilled,” my emphasis). In Antonioni’s case, this has to do with, as he once put it, the “indivisible whole [neither just sound, not only image] that extends over a duration of its own which determines its very being” (my emphasis again).

TD: I would like to reiterate the idea of nothingness as both death and its opposite, something like possibility—anything out there in the universe that can’t be framed or controlled seems worthless or meaningless, but in reality contains meanings that escape us because we are beings trapped in our own time, and we need the future to look back at us. This also makes me think of Melville’s Moby Dick. Is the blown-up image, magnified to nothingness, similar to what Melville is saying in the chapter discussing the whiteness of the whale? Moby Dick the whale is so immense, just like the universe, that he defies meaning—not unlike a blown-up photograph that, in enlarging reality, seemingly erases it? Cortázar’s text alludes to this tension as well, in the section of the story where he mentions that we should teach children photography, so they will learn to see the world. But in the next paragraph he says by tunneling our gaze, we miss out on the wide open world, because inherent in the act of watching is appropriation:

But in all ways when one is walking about with a camera, one has almost a duty to be attentive, to not lose that abrupt and happy rebound of sun’s rays off an old stone, or the pigtails-flying run of a small girl going home with a loaf of bread or a bottle of milk.

Do you all think Antonioni’s idea of the indivisible whole also applies to the mime players who appear at the end of Blow-Up and invite Thomas to join them for a game of mime tennis? The mimes don’t talk but use movement to define objects and “translate” both image and sound. Is Antonioni saying that silence—assuming it means something close to Zen detachment, or John Cage’s theories on silence—is superior to merely watching, as one is not appropriating anything, but embracing and transporting the reality before it? The mimes, with shifting gestures and motions, make time and space cohere, as their scene can change from one minute to the next, and the object(s) of their game can also change to other things as well. Thomas at first stands on the sideline, but then one of the players asks him to throw back the invisible stray tennis ball, and suddenly the audience hears the rhythm of the game, before the film’s fadeout.

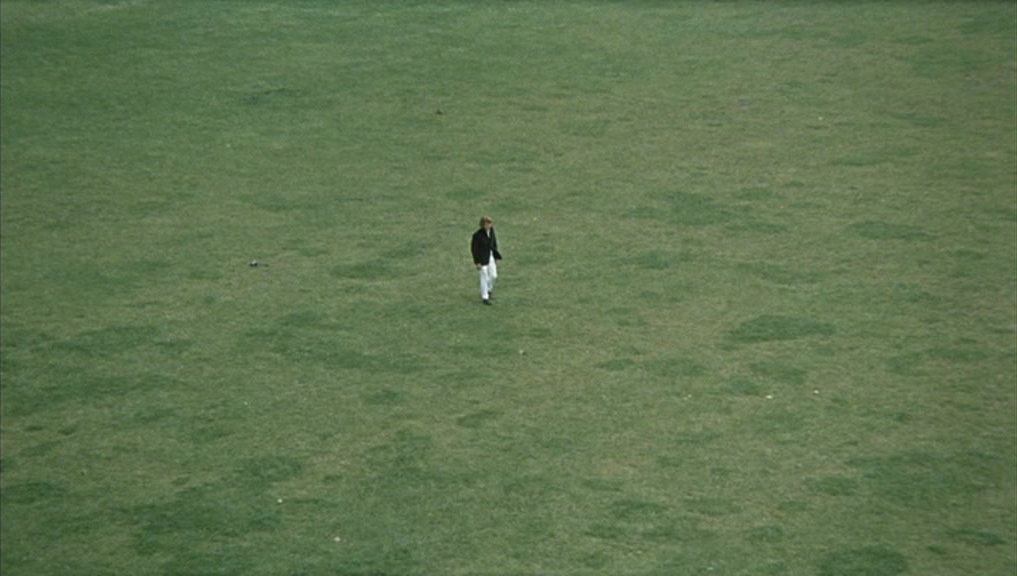

XYS: The final scene in Blow-Up with the mimes is exactly what came to mind, when I was thinking about nothingness! When I watched the film the first time through, I found it emblematic of wonder, a forceful burst of imagination conspiring with the world to change it. Hemmings is masterful here—that take on his face as it moves from mesmerised, to amused, to sorrowful. The ball is created by the flurry of human action, by the trajectory of projection. Later, however, watching it again and again, I began to see something different—a despondent, vacant trick of the mind. The ball was not beautiful because it was imagined; it was deceptive, and the sole focus of its deception removes one from the ability to move towards something better. At the back of my mind was the passage of Cortázar’s that you had quoted, “the decomposition . . . of any reality.” So much goes on in those last few minutes, the whole world splits into two factions. In the opening scenes, the mimes tore through the city in that reckless, aggressive joy, put in such bleak contrast with the orderly file of workers shuffling out of the factory. Their existence, one of frivolity and simulacra, tears into the bigger existence but does not change it, in fact rests on its bleakness; is this a moral interrogation into the escapism of the arts? I still find that scene beautiful. I go back and forth between seeing amazement and despair in creating ex nihilo.

When Cortázar speaks of nothingness, he tells it as “the true solidifier of the scene,” and I was reminded of a poem of Kenneth Rexroth: “. . . nothing. There is / Much more of it than something.”

CT: There is apparently, I agree with Xiao Yue, also hope in that nothing(ness). Where? In translation. How? Intermedially. I am grateful to both Thuy and Rubén for their insistence on the importance of translation and the way in which they tied it in with music. The ball in the final scene remains invisible in spite of Thomas’s joining in the mimes’ game. But it becomes audible, once Thomas throws it back to the player: that’s when we start hearing it bounce in the court. The visual nothing becomes the audible miraculous through intermedial translation, through intermediality.

The only thing I’d like to add is that Beck does smash his guitar (emulating in fact a Pete Townshend routine that Antonioni reportedly had in mind), but in spite of the ensuing commotion, the other guitarist—Jimmy Page shortly before becoming . . . Jimmy Page—keeps smiling and playing his instrument unperturbed. As Thomas rushes out of the hall back into the corridor and then the alley, desperately holding on to the guitar-neck trophy, the sound of Page’s guitar solo still persists in the background. Later on and towards the very end of the movie, the sound of the invisible ball is heard when not only itself, but the pantomime-players are no longer in sight either. The artist-photographer-director himself (there would be also a lot to say about Antonioni’s ever-varying distancing from, and concurrence with, his characters) vanishes into the green-grass background in the last bird’s-eye-view frame as his figure is replaced by the “the end” caption and the music suddenly starts playing again after a really long silence. Cross-artform and intermedial translation thus brings on the urgency of another implicit dimension, the existential one.

XYS: Antonioni’s use of the propeller and the guitar fragment speaks to this in a very pointed Marxian sense: that it is when something cannot function, or is separated from its function in some irreparable way, can we see the object for what it is, can we see the labour and the process innate in its matter. Something so impeccably depicted in Blow-Up is the chillingly empty faces of the crowd as they watch The Yardbirds perform; they come to life only when a splintered limb of the instrument is thrown into their midst. Value is given to the thing that makes the music instead of the music itself, and it is a fierce indictment of complacency in a world that is made to function on our subservience, our dehumanisation. When Michel talks himself into realising the extent of his powerlessness, he screams, he “bursts into tears like an idiot,” and yet right there is when the action of the story halts, and we are taken into the mechanical eye simply looking. It was interesting to me, Rubén, that you saw the clouds at the culmination of Cortázar’s story as something capable of objectivity; I read it that scene as a jarring annihilation of action. Michel has become the very thing he had feared of being—“the lens of my camera, something fixed, rigid, incapable of intervention.” He is on his back, looking at the sky, at “all these days, all this untellable time.” The future becomes a void when we are unable to make decisions, to enact change. The propellor will never fly, the mangled guitar will never again make music, and the image—insofar as it promises that something can be done about what it contains—is impotent. Unless . . .

RL: I concur with what Xiao Yue brilliantly pointed out about the shattered guitar: “value is given to the thing that makes the music instead of the music itself.” This has been the reaction of the capitalistic system towards any innovative or truly disruptive artistic movement during the second part of the twentieth century: to appropriate it and render it innocuous. This is a topic that concerned both Antonioni and Cortázar in different ways. The film insists on these metaphors to represent the frustration of an artist that believes in the transformative power of art but is dealing with an economic system that will probably absorb and commodify it. For Antonioni, someone who, early in his career, denounced class warfare and the bourgeois, it could’ve been a way to express his frustration. Likewise, for Cortázar, commitment to a revolutionary cause was fundamental: utopian thought was on his horizon. He believed in the moral obligation of a writer to unveil the injustices in society and denounce them. However, like many writers of his generation, he had to pay for his commitment to exile and try to send the message while becoming another exotic example of a third-world-country genius for readers in the global North.

Chris Tănăsescu aka MARGENTO is Asymptote‘s editor-at-large for Romania and Moldova. His latest #GraphPoem computational performance, presented at #DHSI22, was a three-hour-long community-engaging #cinemapoetry show, whose shorter version can be watched here.

Thuy Dinh is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Vietnam, Da Màu’s co-editor, freelance critic, and translator. Her works have appeared in NPR, NBC, Prairie Schooner, Rain Taxi Review, among others.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. shellyshan.com

Rubén López is a Guatemalan writer and proofreader. He is an editor-at-large for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Asymptote at the Movies: Drive My Car

- Asymptote at the Movies: Vengeance is Mine, All Others Pay Cash

- Asymptote at the Movies: Love in a Fallen City