In this fantastic, sobering, and imagistic collection, Diaa Jubaili uses the folktale traditions of Iraq to reflect newly on war, country, and national history. Unlike traditional legends, where magic lives in the world as phenomenon and circumstance, the characters of these stories defy their grave realities with feats of imagination, in bold and moving demonstrations of how the mind can transcend matter. In humanizing the struggles of Iraq across its conflicts, Jubaili addresses the horrors of war with philosophical wit and metaphysical possibility.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

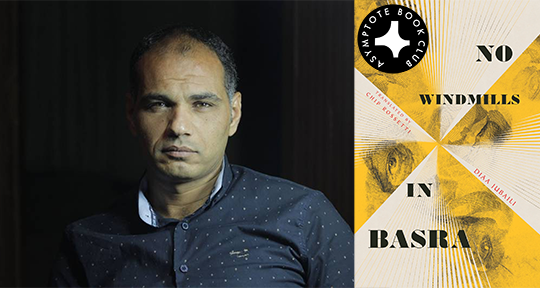

No Windmills in Basra by Diaa Jubaili, translated from the Arabic by Chip Rossetti, Deep Vellum, 2022

On the surface, fairy tales should theoretically be easy to translate (if there is a world in which translation is easy); they’re usually simplistically narrated, lexically limited, and short. But of course, texts that seem simple on the surface can often turn out to be immensely difficult, and in the case of fairy tales, perplexing questions arise almost immediately, because so much of what they impart depends on a reader’s pre-existing cultural knowledge. Can any of us remember a time when we didn’t know the story of Little Red Riding Hood?

The challenges of translation are made even more evident when the fairy tales are intended for adults, as is the case with Diaa Jubaili’s stories in No Windmills in Basra, translated from the Arabic by Chip Rossetti. In this collection of tales—some less than a page long, some ranging over several pages—Jubaili engages slantwise with the history of Iraq and Basra over the past seventy years. Rather than writing a collection of realist fiction, the author departs from reality and time to scratch at those seemingly eternal themes so often associated with fairy tales.

In the opening story of the collection, “Flying,” for example, a security guard named Mubarak thinks often of launching airborne as he guards the chickens at a poultry plant south of Basra.

. . . he flew twice—not on a plane, or by means of a hot air balloon or parachute, and not even on a giant demon’s wings or a magic carpet as happened so often in the tales from the Thousand and One Nights. Nor was he an admirer of the medieval scientist-inventor Ibn Firnas, who dreamed of flapping wings and soaring heights, since Mubarak knew that with that sort of thing, he would eventually end up a pile of broken bones on the side of the road.

There is no magic in this story—at least not the kind we associate with fairy tales—but that does not stop Mubarak from experiencing a journey from the everyday to the cosmic. In his first experience with flight, As an infantry soldier whose company is targeted by bombing, he is tossed into the air after a detonation, being sent briefly into a world where a man airborne is not shorthand for a fighter pilot honing in for the kill, but instead a miracle that allows for deferred violence and peace accords. Of course, Mubarak’s flight comes at the expense of his company, all of whom die in the explosion. Fairy tales are fantastic things, but they’re also dangerous things, and miracles usually have exacting prices. In fact, in this story, American munitions are the only means by which Mubarak can again take flight. The djinns and magicians of the Thousand and One Nights have been replaced by the darker realities of modern warfare.

Jubaili’s tales are not, however, merely a vessel with which to pan American aggression in the Middle East. That implies a far more simplistic approach, with clear-cut villains and protagonists, and often bloody endings. Instead, the collection opens with a brief poetic verse: “There are no windmills in Basra./ Where do I put all these delusions?/ Who am I supposed to fight?” In the cut-and-dry world of childish understanding, the answer would clearly be the Americans; instead, Jubaili’s collection often veers into contemplation not of the righteousness of our stance, but the prices we pay—not only in international conflict but also in love, in literature, and in childhood. In a land with no windmills, Don Quixote can tilt at no one—save his own imagination, which sometimes gets the better of us.

In “The Exchange,” for example, Jubaili imagines a meeting between Gustave Flaubert and Leo Tolstoy. The two writers fight over which of their characters suffers more, Madame Bovary or Anna Karenina. Unable to come to a conclusion, they exchange the characters in order to better experience the pain of the other. While Anna succumbs to Madame Bovary’s arsenic, Emma has other ideas. Rather than meekly going to her death on the train tracks, she avoids Tolstoy at the station and instead smuggles herself into a cab for new adventures with a new lover, beyond the suffering of the modern woman. In Jubaili’s worlds, if violence can be a catalyst for entry into the fantastic of the fairy tale, so too can mischief, love, and mourning.

While many of these tales are relatively straightforward, for a reader ungrounded in Middle Eastern classics, some of them refuse easy understanding. This is where Rossetti’s translation becomes so key to the collection’s success, and he employs a few methods to let us glance around the corners of the roads we have never tread before. No Windmills in Basra opens with a foreword from Rossetti, which gives us background on Jabairi and explains some of the history and linguistic characteristics of these short tales. A few of the stories also have notes at the end, providing cultural context. But even so, I more admired moments when Rossetti refused to explain, and I was left with a sense that I was missing something. This is a difficult choice to make in translation; editors often demand clarity, and readers often respond negatively when they feel they haven’t gotten an “authentic” reading experience. But just as Jabairi’s tales view Iraq and Basra slantwise with a wry grin, so too should we readers feel occasionally off kilter.

Take for example the tale “Graveyard.” The main character Nasir enters the world of the dead through a graveyard, trailing behind him a path of “damp, reddish, sorrowful dirt.” His filth offends his fellow ghosts, who demand to know why it is that he is marked when they are not.

That’s when he told them, with a bitter expression that he nearly choked on:

“I was a soldier and this is the nation’s soil.”

The tales of No Windmills in Basra always end in stingers. They are meant to pose a riddle to the reader, and often the riddle is answered pointedly within the text—but in this case, I felt like I was hearing the answer through the curtain between life and death. Is Nasir’s soil from all of the graves he has dug for fellow soldiers—or from all of the men he has put in the grave? Is it from all of the traveling he has done, having been deployed in every part of the country? Is it the earth he has been made to carry, as Atlas is made to carry the Earth? Is Nasir’s bitterness directed at the nation? Or at his enemy? There are ways of translating this sentence that would make it clearer, that would prescribe a reading to us. “I was a soldier and this is our nation’s soil.” “I was a soldier and this is the nation’s dirt.” “I was an infantryman and this is the nation’s soil.” By tweaking one word one can add a nationalistic tone, a hint of cynicism, or a sense of distance, but Rossetti’s choice to present Nasir’s words simply and dryly exacerbates the opacity. We cannot understand precisely the tone in this last stinging moment, and I think it’s for the better that we don’t. Jubaili’s project in engaging with such brief tales is clearly not to provide moralistic parables; instead, he uses mechanisms of the fantastic to peel away the surface clutter of the daily news, engaging with deeper questions of love, war, family, and violence in a country too often painted with a simplistic black and white brush.

Laurel Taylor is a translator, writer, and scholar currently working on her Ph.D. in Japanese and comparative literature through a Fulbright at Waseda University. Her writing and translations have appeared in Mentor & Muse, The Offing, The Asia Literary Review, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Announcing Our August Book Club Selection: The Left Parenthesis by Muriel Villanueva

- Announcing Our July Book Club Selection: The Lisbon Syndrome by Eduardo Sánchez Rugeles

- Announcing Our June Book Club Selection: Alindarka’s Children by Alherd Bacharevič