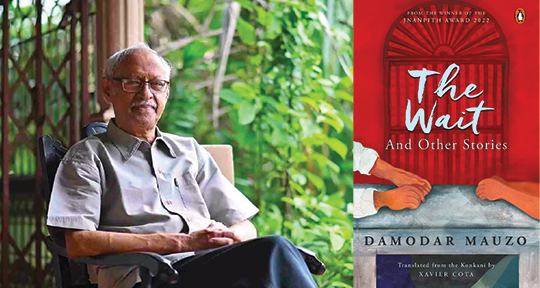

The Wait and Other Stories by Damodar Mauzo, translated from the Konkani by Xavier Cota, Penguin India, 2022

Damodar Mauzo is a short story writer, novelist, and critic hailing from the Indian state of Goa. He writes in Konkani and his works have been translated into English by Vidya Pai in addition to his long-time collaborator, Xavier Cota. The Wait and Other Stories, a short story collection, has been translated by the latter. In 2021, he was the recipient of the Jnanpith Award, India’s highest literary honour. The writer Vivek Menezes calls Mauzo “an exemplar of Goa’s fluid cultural identity, marked by an unabashed pluralistic universalism that persists despite threats and depredations.” His stories seamlessly bridge the gap between timeless and current, invoking the great short story writers of the nineteenth century—de Maupassant, O Henry, Saki—in terms of how often they take an unexpected turn at the end, but also modern practitioners of the form in post-Independence India like Anjum Hasan and Aruni Kashyap, in the way they evoke both a local and national sense of place.

Goa’s history is tumultuous much like the rest of India, but it is also unique due to its separate, and much longer, history of European colonization. In the fifteenth century, it was ruled over by the Adil Shahis of Bijapur. The Portuguese overthrew them and claimed Goa as their territory in 1510, a sovereignty that remained in place for more than four centuries. As such, Goa was never a part of the British Empire and its Indian holdings. Therefore, India’s eventual independence from British rule in 1947 did not impact its Portuguese-controlled status. When the newly established Indian government asked Portugal to cede all its territories on the subcontinent, it refused. As a result, India invaded to annex Goa, along with the Daman and Diu Islands, into the union in 1967. For two more decades, Goa remained just a union territory after a referendum but was eventually designated as the twenty-fifth state of India in 1987.

Goa’s shifting dynamic of languages and religions is a microscopic model of India. While Portuguese is no longer a widely spoken language, older speakers are still present. The official language of the state is Konkani with the highest number of speakers. Marathi is prominent as Goa shares its boundaries with Maharashtra. Hindi, Kannada, and Urdu are the other demographically less represented languages. In terms of religion, Hindus are the most populous followed by Christians and Muslims. These tensions and tussles lie under the surface of Mauzo’s stories. In “Yasin, Austin, Yatin,” a cab driver tailors his identity to every client to win them over and gain big tips: “He had learnt by experience that by making use of religion and caste card, he could win anybody’s heart.” So he switches his name, modifies his commentary, and adjusts the tour to carefully pander to the sensibilities of each customer. As Yasin, the Portuguese are cruel conquerors; as Yatin, they are forceful evangelists; and as Austin, benevolent liberators.

All of these tensions, particularly in the context of post-2014 India, become startlingly palpable in the chilling last story of the collection, “It’s Not My Business,” which follows a carefree and unemployed not-so-young man who occasionally works as a minor political functionary. Babgo is the very image of the liberal centrist who has strong opinions on nothing and who always toes the non-committal middle line. He is akin to the speaker of Martin Niemöller’s heavily quoted poem, “First they came . . .” Bagbo glides through the religious and political conflicts taking place in his village and ignores the problems faced by the villagers as long as he remains unaffected. His mantra is, “I do not interfere in anybody’s affairs. It’s not my business.” Mauzo critiques all political parties with respect to how false assurances are given and how corruption is rehabilitated but he indirectly singles out BJP, currently in power at the centre as well as in many states. He references its promises of bringing back black money to add 15 lakh to every Indian’s bank account, its disastrous decision of demonetization, and its free rein to the deadly vigilantism of gau raksha (cow protection) groups who have killed people just on the suspicion of slaughtering cows and eating beef.

It is apt that “The Wait,” the very first story, provides the title to the entire collection because it thematically cuts across most, if not all, of the stories. The protagonist, Viraj, declares that he would rather get married to Sayali who does not meet his sister’s approval, or always remain single. Sayali, on the other hand, plans to make him wait for a year to see if he remains true to his vow before resuming their relationship. There is much to be said about the anticipatory nature of the act of waiting. It becomes infinitely intolerable when we are aware of the objective of the wait and we desire the outcome. On the obverse, being unaware of the reason can be similarly debilitating, for the wait then seems pointless. For Mauzo, in a Beckettian fashion, human existence is defined by waiting, by our need to pass from one moment to the next as the past eats away at the present and the present collapses into the future, all of it limned in uncertainty and the futile wish to occupy a “now” that will always be practically uninhabitable.

This waiting takes different shapes in the various stories. Whether it is waiting for the pin to drop and for the secret to come out, or waiting to have the final word and close a chapter in one’s life. In “Burger,” Irene shares a beef burger with her best friend, Sharmila, while ignorant of the fact that Hindus do not eat beef—let us keep aside the unquestioned generalization of Hinduism implicit in such a universal claim—and dreads the moment when Sharmila will finally ask about the burger’s provenance. In “I Was Waiting For You,” Mini and Manmohan have been in a relationship until Mini is sexually assaulted and her unapologetic public fight for justice drives the latter away until they reunite after many years with the hope of finally saying to each other what they have wanted to for so long.

A few of Mauzo’s stories also have meta aspects where the protagonist is a writer figure, seemingly a stand-in for Mauzo, struggling to come up with a story and in the end, the one he ends up writing is the story we are reading. In “I Haven’t Tied My Shoelace,” the writer protagonist is waiting for some kind of inspiration to strike so he can submit a story to his editor while he muses about old romances, past flames, and the woman he eventually married. In “Gentleman Thief,” yet another writer suffering from yet another writer’s block strikes up an acquaintance with a well-mannered thief who came to burgle his house. The latter turns out to be a college lecturer who steals the writer’s manuscript to convince him to visit his class for a talk. The story seems to be a homage to Franz Kafka and it is peppered with slightly absurd elements, especially the habits and actions of the thief. Both these stories explore craft and composition, while drawing attention to the act of writing.

Unrequited romance is yet another thread that binds some of these stories. In “The Jalopy,” the first-person narrator Rajesh recounts a story from his youth of when he met a woman called Veena at a seminar. She persuades him to propose marriage to her as her father is about to finalize her match. The plan is unable to come to fruition as Rajesh gets lost and cannot find her house within the critical period. In “The Lover of Dreams,” Mukut, a migrant worker skilled at carpentry, falls for a young girl who crosses his path; class and religion separate them. He christens her “Katrina,” imagines romantic scenarios, and obsessively stalks her from a distance, even after she is married. Both these stories evince a different kind of waiting, created either by indecisiveness or plain fate. While Rajesh gives up to make a life of his own, Mukut remains trapped in the dream.

There are also stories of love soured and of infidelity. The narrator of “The Aesthete” has a taste for all things beautiful, so he carefully curates his life to maintain his persona as a man of culture. He also chose a “drop-dead beautiful” woman as his wife but when she starts to develop vitiligo, he spurns her and tries to stay away from her. In “Night Call,” a doctor feigns a work call to get away from his wife and keep his planned tryst with a hospital nurse whose doctor husband, also a colleague, is out of town. “The Next, Balakrishna” explores the intertwined nature of colourism and casteism in India, where a fair-skinned woman resents being married to a dark-skinned man even though he dotes on her and misguidedly cheats on him with a Brahmin landlord. In these stories, Mauzo highlights the failings of human nature and critiques the resort to impulse.

Xavier Cota’s presence as the translator is very unobtrusive. His translation is smooth, free-flowing, and easily readable. It is perhaps justifiable to see this as a sign of over-translation. The stories feel naturally written in English, albeit distinctly of the Indian kind. There are no wonky transliterations or calques though the words and phrases retained from the original are sparse and tellingly denoted through italics. As a translator who has worked on multiple books by Mauzo, however, a translator’s note or an afterword explaining some of his choices involved in the process of translation would have been a useful addition to the collection.

Cota calls the conferral of the Jnanpith Award on Damodar Mauzo “[a] singular achievement for a language mockingly denigrated as bolibhasha or dialect [of Marathi].” Indeed, The Wait and Other Stories frees Goa from its narrow popular perception as a glitzy tourist destination to emerge as a place beyond its seascapes and monuments, where people lead regular lives with dreams fulfilled and abandoned, succumbing or triumphing over their struggles.

Areeb Ahmad just got done with a Master’s in English and is doing his best to enjoy a short academic break. He likes to write about the intersections of gender and sexuality across texts. He enjoys exploring how the personal and the political as well as form and content interact in art. He is a Books Editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of Areeb’s writing can be found on his bookstagram, a true labour of love. His reviews and essays have appeared in Mountain Ink, Gaysi, The Chakkar, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: