The O, Miami Poetry Festival is a month-long celebration of verse in Florida’s capital, with the mission of establishing a series of events, performances, and public exhibitions, so that “every single person in Miami-Dade County [can] encounter a poem.” The festival’s programming included a translation workshop held by Layla Benitez-James and Jorge Vessel, consisting of two intensive sessions dedicated to studying, discussing, and building upon the complex art of poetry translation. In the following dispatch, Benitez-James gives us a behind-the-scenes look at the going-ons of the workshop, and presents the fruits of the translators’ labour: a poem by Colombian poet María Gómez Lara.

At the end of April, across two continents and various time zones, a group of translators met virtually to discuss, translate, and workshop the poem “palabras piel” by Colombian poet María Gómez Lara. Organized by O, Miami in partnership with the Unamuno Author Series (UAS), the creative task was set as part of a translation workshop lead by two members of the UAS team: award-winning Venezuelan writer, translator, and engineer, Jorge Vessel (pseudonym for Jorge Garcia) and myself, a writer and recent winner of an NEA in translation. Over two sessions in consecutive weekends, we discussed translation theory, inspiration, and collaborated on a wonderfully challenging poem.

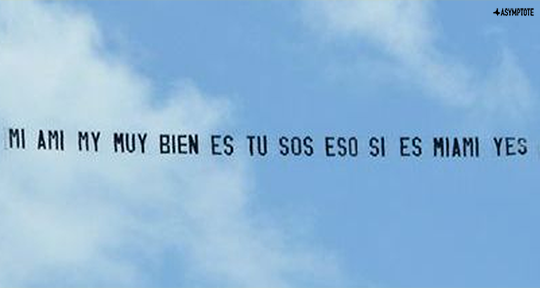

The translation workshop was hosted by O, Miami Poetry Festival Founder and Executive & Artistic Director P. Scott Cunningham, who took part in the inaugural Unamuno Poetry Festival in Madrid—the city’s very first anglophone literary festival (Scott’s poem “Miami” from his collection Ya Te Veo was translated into Spanish by Jorge for The Unamuno Author Series Festival Anthology). While the aim of the O, Miami festival is to help each and every person in Miami encounter a poem throughout the month of April, our personal goal in 2019 was to introduce over eighty poets and academics to Madrid’s literary community; as such, translation between Spanish and English has become an important part of both organizations.

Our objective for the workshop was to inspire and embolden participants to take up a translation project of their own, as well as to broaden their ideas of what those projects might entail. While we would open up a discussion about basic elements of translation, we also wanted to expand upon how these writers and translators thought about the overlaps and symbiosis of their creative processes—how the act of translation itself can be the spark or jumping-off point for inspiration.

In the first session, we took a look at “36 Metaphors for Translation”—gathered by Jessie Chaffee for Words Without Borders—and thought about how we might describe and understand the process by comparison. The group had diverse individual motivations behind their translation practices but were unanimous in wanting to amplify voices through making their works available in English. Many were already proponents of collaboration, believing in the importance of having more than one person participate in a translation in order to think through different possibilities and interpretations. In the end, the translator must be the best reader of the text to bring it into a new language and context, but they can always have help.

After presenting some techniques and tactics for translating literature, with an emphasis on the subjective and evolving nature of the practice, we compared translations of the opening lines of Dante’s Inferno—compiled in artist Caroline Bergvall’s VIA: 48 Dante Variations. I’m especially fond of listening to Bergvall read the piece aloud, as her accent has a wonderful mix of influences; she’s mostly lived in the UK, but she was born in Germany with a Norwegian father and a French mother. In addition to hearing the compiled text live, we listened to a few minutes of this opening of Dante’s Inferno in Italian (Allen Mandelbaum’s translation is used for the captions). I like this recording because it provides the Italian text in addition to the English translation, so one can both hear and see these rhymes, then return to the English translations with our ears more attuned to the music.

Dante’s Inferno and these opening lines have held a special place in my creative imagination, but reading and hearing the versions tumble out one after the other also reminded me of how many infinite possibilities there are in translation, and how we are often just moving towards the best version we know how to make. Bergvall composed her found poem in 2004 after reading through the nearly two hundred English translations at the time, but I was introduced to the project after poet Mary Jo Bang translated her own version in 2012 for Graywolf Press, and I’ve since obtained a 2018 version by the late Scottish writer and illustrator Alasdair Gray. Aside from what comparing different versions of the same text could teach us about our smallest choices, looking at this experimental text got us fired up about the infinite lives of literary texts, even after they are translated hundreds of times.

In our second session, we got down to business! Our plan was to have participants put their new skills to use in collaboratively translating a poem, and Jorge had the brilliant suggestion of María Gómez Lara, who had given an electric virtual reading for the Unamuno Authors Series on June 26, 2020—when all of Spain was still locked in a strict mandatory period of confinement. Not only could we work together to collaboratively arrive at a translation, María herself would join us after we finished our first draft to answer questions and provide additional insight. María had just moved to Madrid after finishing a PhD at Harvard, and she was thrilled by the close attention the team poured over each and every line of her “palabras piel.”

To build our draft of the poem in English, participating translators Annie Schumacher, Elisa Menéndez, Lucia Herrmann, Lupita Eyde-Tucker, and Laura Elliott each began by making a rough draft on their own. Everyone spoke of being completely enchanted by the poem and equally unsatisfied with where they had landed with their draft, and Harriet Martin (who joined us for the collaborative second session) highlighted the text’s ability to pack multiple meanings into seemingly simple lines.

While I fell down a rabbit hole trying to find an English version of the German poem by Rose Ausländer quoted in the epigraph, Annie began with a very literal translation and then pressed on words’ multiple meanings. Lupita wanted to lean towards simple verbs to make the English feel as plainspoken and direct as the Spanish, but felt “painted into a corner” in trying to watch out for easy cognates, and felt unsatisfied with “and like that” for “y así tener un cuerpo.” There were many challenging verbs to mull over; escoger could be pick, choose, select and tener could be the more direct to have or be slightly elevated with an option like to possess. Elisa felt like she made too much of a “xerox” on her first attempt (referencing the Willis Barnstone quote from our first session: “A translation is an x-ray, not a xerox.” from “An ABC of Translating Poetry”) so she recombed over the poem, focusing on the rhythm and tone. Similar to Lupita, Laura strove to recreate the simplicity with all the multiple depths of meaning she was perceiving in the original, and she noted that she went to bed with the poem on her mind an woke with tweaks for her draft before she sent it in. None of us were satisfied with our treatment of aturdimiento which could be bothersome, dazed, bewilderment, shock, confusion. Laura offered “muck” which made the line more poetic and imagistic, and for a while we thought that might be a more radical fix. However, we came to some agreements and were more than ready for María to make her entrance. We listened to her read the poem in the original Spanish a couple times, then read our English version and began to discuss options. María especially appreciated our struggles with aturdimiento and said it needed to feel a bit awkward, a bit confused with its ungainly six syllables (and muck was actually too elegant, too tied into a wonderful image which we all agreed could and should be used later, by someone, in a poem). After our conversation, we arrived at the English translation presented below.

Amazingly, Lucia met a Brazilian woman on a train and had a conversation about the translation, talking through some differences between Spanish and Portuguese and extending the creative energy of the workshop far outside what we’d originally imagined. It’s our hope that this encounter will spark more collaborative efforts whether they happen at quiet desks, on high-speed trains, or even thousands of feet in the air; translation is everywhere.

skin words

by María Gómez Lara

number words time words

skin words

Rose Ausländer

if I could choose another skin

it would be dark like this one

it would be composed of words

if I could say skin-words

and so possess a body

like this one

but

eloquent

when it shatters

if I had a body that said

for example here I am I haven’t gone for example I endure

a body that gave hows and whys

and not this bewilderment this fatigue these bones nearly ground to dust

from such breaking

how much then I’d understand:

if I had words

instead of scars

palabras piel

palabras número palabras tiempo

palabras piel

Rose Ausländer

si pudiera escoger otra piel

sería oscura como la mía

y estaría hecha de palabras

si pudiera decir palabras-piel

y así tener un cuerpo

como el mío

pero

elocuente

al quebrarse

si tuviera un cuerpo que dijera

por ejemplo aquí estoy no me he ido por ejemplo sobrevivo

un cuerpo que diera razones y porqués

y no este aturdimiento este cansancio estos huesos casi polvo de tantas veces rotos

cuánto entendería entonces:

si tuviera palabras

en vez de cicatrices

Layla Benitez-James is a 2022 NEA fellow in translation and the author of God Suspected My Heart Was a Geode but He Had to Make Sure, selected by Major Jackson for Cave Canem’s 2017 Toi Derricotte & Cornelius Eady Chapbook Prize and published by Jai-Alai Books in Miami. Layla has served as the Director of Literary Outreach for the Unamuno Author Series in Madrid and is the editor of its poetry festival anthology, Desperate Literature. Poems and essays can be found at Black Femme Collective, Virginia Quarterly Review, Latino Book Review, Poetry London, Acentos Review, Hinchas de Poesia. Audio essays about translation are available at Asymptote Journal and book reviews of contemporary poetry collections can be found at Poetry Foundation’s Harriet Books.

María Gómez Lara (she/her) has published three poetry books: Despues del horizonte (2012), Contratono (Visor, 2015) and El lugar de las palabras (Pre-Texts, 2020). Contratono was awarded with the XXVII Loewe Foundation International Poetry Prize for Young Creation and has been translated into Portuguese by the poet Nuno Júdice under the title Nó de sombra (2015). Some of Maria’s poems have also been translated into Italian, English, and Arabic, and have appeared both in Spanish and in bilingual editions and anthologies in Latin America and Spain. Maria studied literature at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá. She has a master’s degree in creative writing from New York University and another in literature and romance languages from Harvard University. She is currently working on her doctorate in Latin American poetry.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: