What makes us who we are, what shapes and defines us? Is it the country that we come from or the language we speak? Is it our sex or sexual orientation? The generation or political system into which we were born? Is it our job, the class we belong to, or the education that we are privileged with or denied? Is it our family, and, if so, as one character from Elena Medel’s The Wonders puts it, “What if genes determine your character, not just your eye colour or the shape of your mouth?” And in all this, how much is pre-ordained, what role is there for choice and free will?

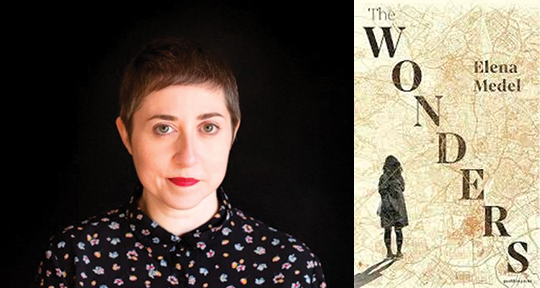

Medel’s debut novel, translated from the Spanish by Lizzie Davis and Thomas Bunstead, does not presume to offer a single, clear-cut answer to these questions, but one thing is obvious right from the start through the Philip Larkin quotation she has chosen as an epigraph: “Clearly money has something to do with life.” Weaving together the stories of three generations of women from a single family over the course of half a century, from the ’50s to the death of Franco in 1975 to the 2018 Spanish Women’s Strike, the novel seems to suggest that gender clearly has something to do with it, too.

As the novel opens, Alicia (the third generation in the family), finding herself without “so much as a used tissue,” feels uncomfortable from the sense of material limbo. Even at the age of thirteen, she understands that “money tempers [mediocrity], helps to conceal it.” Although she defines her life through money, or the lack thereof, her experience has also been shaped by another great absence that is inextricably linked to financial ruin: that of her father, who feigned the life of a successful businessman while getting increasingly into debt and committed suicide after a bungled attempt at life insurance fraud. From thereon out, Alicia is denied the expensive school and new apartment she’d expected and must move back to the suburbs of Córdoba, eventually moving to Madrid and a mundane life of insecure work and an unsatisfying relationship of convenience punctuated by anonymous casual sex with men who she can approach cynically as “safe bets.”

María, Alicia’s grandmother, shares a great deal with her granddaughter—birthplace, gender, family, and class, as well as a lifelong wondering about what could have been—and it is their stories that the novel intertwines as it jumps forward and back in time between 1968 and 2018, and from one character’s perspective to another’s. But these characters are also very different: while Alicia remains defiantly childless, María becomes pregnant with Alicia’s mother, Carmen, at 16; where Alicia is quite solitary and spiteful, even before her father’s suicide, María—though she was denied the chance to express her maternal instincts directly—takes on the role of carer in other situations and spearheads the formation of a women’s division of her neighbourhood association. Nevertheless, she sees her life as having been defined by the same key thing as Alicia does:

Money’s the thing: not having enough is the thing. Every one of the situations that brought María here…would have unfolded differently if there’d been money.… If her parents had had money back then—if they were well enough to earn it, had enough of it to stay well—would she have met that man, on that bus?… For money, she had to leave home before she was ready, replace her daughter’s scent with that of someone else’s son. The apartment she lives in is the apartment she can afford, not the apartment she’d like to have, and her job is the one, being who she is, having the money she’s had, to which she could aspire.

Despite this, María’s relationship to her lack of money is very different from Alicia’s. Alicia takes pride in her good fortune when she has it, becoming “shameless to the point of boastfulness” and stubbornly refuses to try to improve her lot. She drops out of film studies at university—“she just wanted to make money and didn’t care much, if at all, about art”—and then gets stuck in one poorly paid job after another while she half-heartedly ponders a different course. María, meanwhile, saves up to take herself to movies and reads voraciously, trying to give herself the education that was never available to her. Alicia seems to agree to marry her boyfriend for convenience and stability rather than love or even deep attraction, while María breaks up with her long-term boyfriend when he suggests she move in with him to save on rent. Clearly, money is important to María, but it is a means to an end, and she always puts her independence, intellectual life and social engagement first.

The difference in the opportunities available to Alicia and María is evident, and not just because of Alicia’s brief stint in a higher class: while the work of feminism is far from over, Alicia’s life is evidently far less shaped and constrained by having been born female than is María’s. María is painfully aware that, having been born in the middle of the twentieth century, her gender has been just as much an impediment to her success and independence as her class. Alicia resists many ideals of femininity and always ensures that she holds the power in her sex life; she perhaps represents in parts an idea of feminism centered on sexual freedom without the constraints of motherhood. María, on the other hand, knows that her life would have been different if she were not limited by the conventions of femininity and the realities of the female body. Were she not a woman, she would not have fallen pregnant as a teenager and been sent away; were she not a woman, she would have had more opportunities for work than caring for other people’s babies or dying parents, and her ideas would be respected, just as they are when her boyfriend ventriloquizes them later on. She only ever speaks to the older, married man who is Alicia’s grandfather father because “saying nothing seemed rude.”

While this novel is often described in reviews as having two key characters, there is a third woman in this constellation whose absence—both on the pages and in the lives of María and Alicia—registers just as strongly. Carmen, the middle woman in this three-generation saga, is a stranger to María, who was compelled by her own mother and her economic reality to leave her daughter behind when she moved to Madrid; Alicia, by contrast, chooses to become estranged from Carmen, clearly blaming her mother in part for the expectations of a comfortable life that may have pushed her father to suicide. Whereas María takes a path of resistance, and Alicia one of a strange mixture of defiance and resignation, plagued as she is by the recurrent nightmares of her father’s death, the woman who both separates and connects them quite literally figures a possible middle way. Carmen seems to passively adjust to her lot in life without ever really taking responsibility; when she falls pregnant, also as a teenager, she gets married; when her husband’s businesses seem to succeed, she plays the part of wealthy housewife; when her husband dies, she “swallowed her pride and started over,” working for the rest of her life in her uncle’s restaurant. She even accepts her distance from mother and daughter, whereas Alicia and María constantly wonder about the other women missing from their lives.

Alicia considers her mother’s—and the family’s—downfall to have been Carmen’s ambition, never considering the impact on her mother’s own life of her perceived abandonment and teen pregnancy. When thinking of her own desire to be distant from the world, Alicia reflects that

her mother shattered that wish, her hands soft from avoiding work, the ambition to have more than her share, to hide…the place she came from, the bedroom she’d shared with Uncle Chico and Aunt Soledad, the habits of someone who’s had nothing and suddenly doesn’t have everything, but almost.

Despite this ambition that verges on a sense of entitlement, Carmen is defined by passivity and withdrawal. She leaves school but becomes pregnant before getting the job she’d planned; she stays home rather than engaging with her mother, and the farthest she gets from her birthplace is a neighbouring suburb. In one of the only scenes in which she appears outside of a photograph, she has withdrawn from the world in a long siesta. Abandoned by her mother, Carmen learns to let the world happen to her instead of trying to shape it, but this outlook leaves her bitter: “I was amazed by the way she removed herself from the situation, her problems and his, some stranger hanging from a tree. My uncle would interrupt from time to time and ask her not to be so harsh, to try to understand, but my mother raised her voice, and she always found a way of saying something cutting.” One of the strengths of this novel is that none of the characters is a simple caricature, and even in the passivity of her actions, Carmen is more than just a placeholder for the other women’s desires and disappointments.

Three women, three generations, three varying approaches to similar situations. While María is perhaps the most sympathetic of the characters, the quiet, restrained prose of this novel, translated with great poise by Davis and Bunstead, is never sensationalist or sentimental and does not seek to condone or condemn the choices its characters make or those they abstain from. Despite focusing on people who have endured poverty and misfortune, this is not slum voyeurism–what María at one point calls “the comfort of reading stories worse than my own”– nor does it offer catharsis. Instead, The Wonders offers a sober and sobering snapshot of the role of gender and class in modern Spain.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English and a senior copyeditor with Asymptote. She holds a master’s in translation and in 2016 won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme. Her first full-length non-fiction translation has recently been published with Scribe.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: