Switzerland’s multilingualism has long been an inextricable part of its national identity, but how is this amalgam really implemented in everyday life—and how is it reflected in the country’s literature? Ahead of the Swiss Special Feature in our Summer 2022 issue (by the way, translators of this country’s literature are invited to submit work—and stand to receive an honorarium of USD80 if their work is accepted—by June 1), Swiss translator Zorka Ciklaminy sheds a light on the reality of living within this complex intersection of speaking, living, reading, and writing. The Berlin-based writer and translator Katy Derbyshire translated the following piece from the original German.

The Swiss Language Landscape

Switzerland is a country coloured by multilingualism; German, French, Italian and Rhaeto-Romansh all have equal standing as official national languages. Yet, this presumed quadrilingualism does not unilaterally apply to all those living in Switzerland, since it is not the case that the entire population speaks all four languages; the country instead consists largely of monolingual regions, with little dialogue between them. Along the language boundaries, and in the multilingual cantons (Bern, Fribourg, Graubünden and Wallis), however, many people are bi- or multilingual, and in areas such as German-speaking Switzerland, we see a varying bilingual phenomenon: High German may be the official language, but in everyday life people speak Swiss German—a collective term for various Alemannic dialects.

How is this multilingualism lived on an individual and societal level, and used in everyday communication? As one might suspect, the answer is not entirely clear or logical at first glance. Though the country’s everyday multilingualism does not differ essentially from that of its neighbouring countries. It must be emphasized that dialogue between the linguistic communities is actively promoted by the Swiss government, with a language law stipulating, among other things, that Italian and Rhaeto-Romansh—underrepresented languages compared to German and French—are to be maintained and promoted as national languages. However, it is obvious that when we speak of a multilingual Switzerland in this age of globalization, and of English as a rising lingua franca, our focus cannot possibly remain solely on the official national languages—which would not reflect Switzerland’s linguistic diversity, excluding a large part of the country’s residents. Instead, one should be attentive to what are still frequently referred to in Switzerland using the rather infelicitous term “fifth national languages”.

In a country of immigrants, like Switzerland, migration-led linguistic diversity plays an emphatic role in formation of new language communities. After the end of the Second World War, the 1950s and 1960s saw the arrival of political refugees from Hungary, Czechoslovakia, and Tibet, along with a larger group of labour migrants—known as Saisoniers—from Italy. During the 1980s and 1990s, migrants came mainly from southern and south-eastern Europe (Spain, Portugal, the former Yugoslavia and Turkey) and Sri Lanka. Following the 1999 Treaty on the Free Movement of Persons between Switzerland and the EU, further immigration occurred from central and eastern European states. This development prompted numerous languages to spread in Switzerland over the decades, forming a linguistic potpourri. In more specific terms, this migratory multilingualism means that these migration languages combined are spoken by more people in Switzerland than Italian and Rhaeto-Romansh together. For many years, the fact that this has led to new literatures in Switzerland was neglected or even ignored.

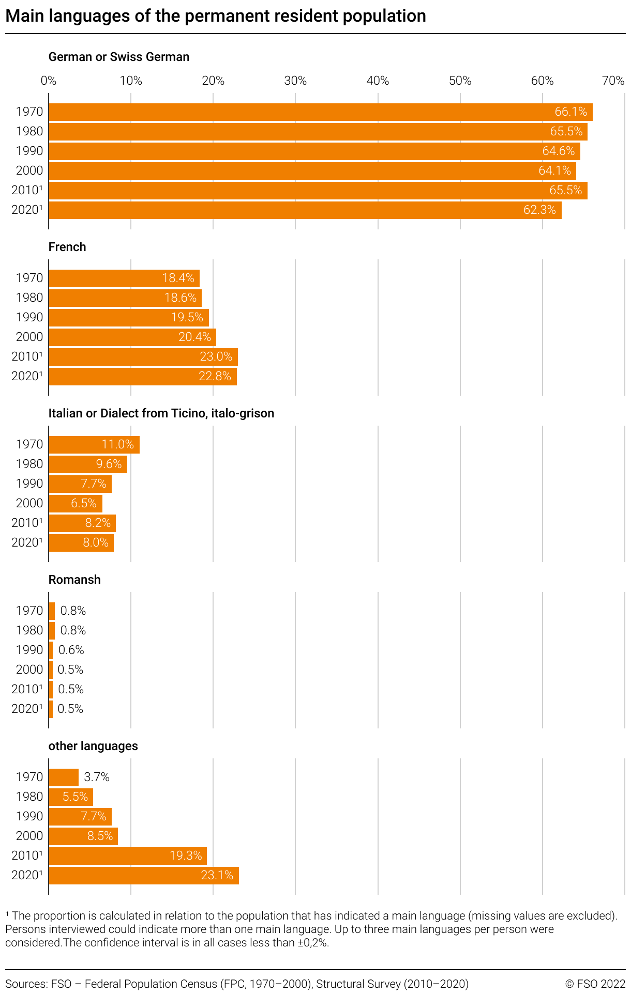

In the Federal Statistical Office’s 2020 survey, Switzerland’s main languages were German (62.3%) and French (22.8%), followed by Italian at 8% and Rhaeto-Romansh at 0.5% of speakers. Other languages made up a combined share of 23.1%, whereby respondents could state up to three main languages:

It is interesting that—aside from French, which has seen a 4.4% increase since the first statistical survey in 1970—all other official main languages have seen reduced speakers. For the migration languages (shown here as other languages), however, the opposite is the case. Having represented a share of 3.7% in 1970, by 2020, there was a rise of almost 20% in Swiss residents giving a non-official national language as their main language. The two most frequently spoken non-official languages are English (5.8%) and Portuguese (3,5%), followed by Albanian, Spanish, Serbo-Croat, and other (not listed) languages. This comes as no major surprise, but it is only by considering these figures that we can develop awareness of how rapidly linguistic change has taken place in Switzerland over the past two decades in particular—making not quadrilingualism but multilingualism a reality in society. Yet how does this change bleed into Switzerland’s literatures?

Heterogeneous Literary Scene in Flux

Though a part of Swiss literary identity, the increasing influence of everyday multilingualism on the country’s literary world is not a process that took place naturally, but as a result of initiatives taken by many individuals: multilingual writers, enthusiastic publishers, and supporters alike. It appears that some semblance of a multilingual reality has only recently been welcomed into the Swiss literary industry in all its diversity—an overdue and pleasing change—and the issue is continuously discussed, both inside the literary world and publicly in the media. Numerous institutions and festival organizers have taken up the cause of integrating writers of other national languages into the literary community (or are taking the steps to), and granting them their rightful space.

In German-speaking Switzerland, for instance, there have risen such initiatives include Artlink, which promotes writers and other creatives from various regions of the world in Switzerland. Additionally, Weiterschreiben Schweiz, founded in Germany and extended to Switzerland in 2020, is a successful online platform for writers from war and crisis regions, who are making texts accessible in two languages. For the past two years, the largest Swiss literary festival, Solothurner Literaturtage, has also included a focus on raising visibility for writers of other national languages. The Babel Festival di letteratura e traduzione in Italian-speaking Switzerland is also worth mentioning. In growing numbers, writers from Syria, Iraq, Iran, Yemen, Sudan, and Afghanistan are forming relationships with renowned Swiss authors and holding bilingual readings together. In short: all these initiatives aim to open doors to the local literary industry, enabling artistic exchange and publication opportunities in Switzerland.

Literary translators undoubtedly play an important part in this process. Should publishers become aware of writers previously unable to publish their work (due to censorship or language barriers to the Swiss book market), the ideal result would be new books. This strategy has succeeded, for example, in the case of the writer Hussein Mohammadi, born in Afghanistan and raised in Iran; having fled to Switzerland in 2013, he is about to debut his first novel, translated into German with a Swiss publisher.

Such success stories are, as of now, still rarities; the fact is, most writers who continue to work in their native languages in Switzerland go essentially unnoticed by the general public, even if they have lived in the country for years. They are—there is no other way to put it—blank spots on the literary map of Switzerland, yet they are read in their countries of origin, and their books are frequently successful. The Swiss-based poet and translator Sergey Zavyalov, has received the highly respected Andrei Bely Prize, and remains one of Russia’s best-known contemporary poets. Many literary treasures are hidden in Switzerland, and the time has come to bring them to light!

For immigrant writers who react to their new linguistic surroundings by switching and making the foreign language their own, it is far easier to gain visibility and a foothold in the Swiss literary industry—though that path was still a stony one for the first generation of immigrant writers. The Kurdish author and filmmaker Yusuf Yeşilöz, who left Turkey for Switzerland in 1987 and began writing in German—like all writers of his generation, incidentally—was initially treated as a poster boy for migrant literature (let’s hope that term soon vanishes from our vocabulary!), being invited to readings—in more provocative terms—as a “token foreigner”, and it took years for the literary world to accept him as a Swiss writer. He has now published twelve books in German, and further translated into numerous languages.

These days, writers with other native languages are primarily regarded as enriching the Swiss literary scene, and setting trends with new material and poetologies—for instance, with texts on the wide-ranging experience of migration. Such books leave a clear mark on literary society, as evidenced by the winners of the Swiss Book Prize (limited to German-speaking Switzerland, certainly not making a case for a multilingual literary space); awarded to Ilma Rakuša (2009), Melinda Nadj Abonji (2010), and Catalin Dorian Florescu (2011), the prize went three consecutive years to authors working in German—but with other native languages. In recent years, the Swiss Literature Awards (presented to writers of all four national languages) have gone to Irena Brežná (2012), Marius Daniel Popescu (2012), Christina Viragh (2019), Zsuzsanna Gahse (2019), Pascal Janovjak (2020), Dragica Rajčić Holzner (2021) and Dana Grigorcea (2022), honouring numerous authors who grew up in different linguistic surroundings.

Swiss Language Confusion

In Switzerland, there is no common book market; instead, each market is oriented towards its own linguistic region in the neighbouring countries—Germany, France, and Italy. As a result, Swiss literature is always a minority literature compared to that of its neighbours. What does that mean for literary translators? They not only introduce us to books from other cultures, but also bring Swiss literature from one language region of Switzerland to others; it is their vital work that contributes to awareness for the entirety of Swiss writing.

The Swiss Translators Association currently has 137 members. Adjusted for the size of the country, this is similar coverage to its German equivalent—which unites 1304 literary translators, and the French—with 856 members. Looking more closely at the source and target languages, it is striking that most literary translators in Switzerland work between the national languages: most frequently from French into German (forty-six translators), from Italian to German (seventeen), Italian to French (ten) and Rhaeto-Romansh to German (six). Publications such as the ch Reihe (a series of new publications in translation) and ViceVersa Literatur aim to spread Swiss literature beyond the country’s language borders; as a result, many Swiss translators are working in this field. But what about translators from other languages?

As might be expected, English is a dominant source language, and translators also work from Russian and Spanish. It is an unhappy surprise, however, that translators from even the most frequent migration languages are extremely rare. Translators from Arabic, Serbo-Croat, Turkish, or Persian are more present in the neighbouring countries, so as a result, the aforementioned platform Weiterschreiben Schweiz has to work with translators from Germany. Aiming to counteract this general lack of translators in German-speaking Switzerland and to promote young talents, Translation House Looren has developed an emerging translators programme, designed to help interested students of literature at Swiss universities gather practical experience of literary translation and gain useful advice on how to get a first contract as unknown translators.

To elaborate on the complexity of translating within an intricately multilingual sphere, one must consider dialectical speech. In German-speaking Switzerland, Swiss German is spoken colloquially in the form of various non-standardized dialects. Every Swiss German is in a diglossic situation, using two related languages while also facing a linguistic conflux of media: Swiss German is spoken, High German is written. Swiss German (not to be confused with Swiss High German, as often happens abroad!) is normal throughout society: it is present on radio, TV, in music, and in informal communication via text message, etc. With regard to grammatical structure, the greatest difference between Swiss German and High German is the use of tenses. The tenses system in Swiss German is far less complex: there is no simple past, only perfect tense, and elements in the future are expressed in the present tense. For literary translation in particular, this fact plays a role that should not be underestimated.

When translating, a clear differentiation must be made between which language is more foreign to me and which I am closer to. This can vary from sentence to sentence, word to word, but they can never be equally familiar or foreign to me. In metaphorical terms, the foreign language—the source language—represents one bank of the river, and my own language—the target language—is the other bank. This image is not new, but it still gives the best illustration of what happens during the translation process. If both languages are equally foreign to me, I cannot ferry the meaning, let alone the stylistic and rhythmic characteristics of the text, unharmed from one side of the river to the other. Languages must oppose one another; they can never run parallel during translation.

When High German is not my everyday language, however, I face an additional hurdle while translating, which makes it more difficult for me to make the target text ring true. To put it another way: I’m sitting in a boat with two more or less foreign languages, which are not opposed. This fact could attribute to why so few second-language speakers have the courage to translate from their native language into German (or other languages), despite being perfectly apt to fill this translation gap in Switzerland. Perhaps a new generation of translators, from languages with fewer speakers, might be formed by providing them with mentors with whom they could work jointly on a text—similar to mentorships already offered by some of the aforementioned institutions but slightly different; in tandem and according to the vice-versa principle, a native speaker of the source language could translate a text with a target-language native speaker. Language is so dynamic, equivocal, and open. It is always worth spending time exploring the surroundings of two languages from various distances, in detail and in wide, plumbing its depths. A critical partner can only serve as an advantage for the target text.

Allow me to double up from my own experience. I translate from Slovak into German—a bilateral rarity; I work from what we often call a ‘small language’ that few people speak, and I translate from my native language into German, a foreign language. Among my fellow translators, that causes more consternation than admiration, since an unwritten law demands that we always translate into our native language. I see this differently. I translate into German because I live in a German-speaking space, because I was socialized here and feel intimately the changing lingual tides, and I go along with the change—because I can nourish the German language with my culture, and participate in its evolution. I translate in this direction because for me, both Slovak and German can be very familiar or very foreign by turns, depending on the situation. Slovak is the language of my heart, the linguistic expression of emotions and abstractions, while German is the language of my head, a language of rationality and clarity. It is wonderful to have both languages at my disposal, and to live with them both, and it is also a strength to translate out of a native language into a foreign language, to feel the dialogic transformations between them.

Multilingualism is a gift, because of this generosity. As speakers of multiple languages, perhaps we should take on the responsibility of breaking taboos between languages and within the art of translation, in order for this rich medium to take on its full scope and potentials.

Zorka Ciklaminy is a literary translator working from Slovak, Russian and Serbo-Croatian into German. She grew up in a Slovak-Serbian family in Switzerland where she studied Slavonic languages and literature, Nordic studies and Comparative literature. She works at Translation House Looren and organises public events and workshops for literary translators.

Katy Derbyshire translates contemporary German writing and heads the V&Q Books imprint from Berlin. Her translation of Clemens Meyer’s Bricks and Mortar was nominated for the Booker International Prize in 2018 and won her Germany’s prestigious Straelen Translation Prize. Her most recent translation is Kraftwerker Karl Bartos’s autobiography, The Sound of the Machine.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: