The population control policies of China have been a long, treacherous trial of the invasion of nationhood into the most private corners of personhood. In the following essay, Xiao Yue Shan discusses the literature written under this continual interrogation, the performance of autobiography, and how the intensely personal can come to elucidate the immense.

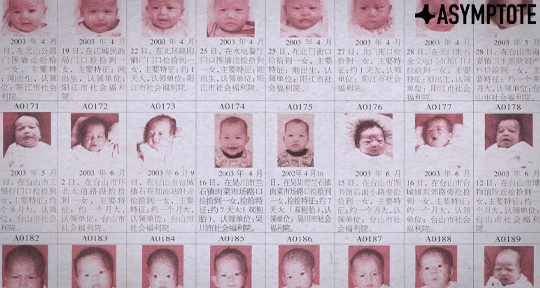

Halfway through Nanfu Wang’s documentary, One Child Nation, the scale of China’s family planning policies begins to hint towards their true proportions—violence that moves past the triangulation of parent, child, and state, towards a vast chaos of capital and globalism. Following a series of tender but unequivocal interviews—in which the director confronts her own family’s trauma of child abandonment and death—Wang addresses the sensational story of a family who had made a living out of selling found children to orphanages, before being convicted and imprisoned for human trafficking. In an interview with the household’s late matriarch, she speaks without hesitation; the amount received for the first child she handed over was 700 RMB—about 115 USD. The camera, both attentive to and suspicious of her watery gaze, makes few observations of guilt or sorrow. She has that same discrepant, hard youth of many rural Chinese women, an aura of won stoicism and fearlessness, even as she relays the brutal details: “I was inconsolable . . . and the orphanage director [said]: ‘You found her? Her own family abandoned her. Why the fuck are you crying?’”

More Than One Child, a memoir by Shen Yang of “China’s Invisible Generation,” opens with an assertation of presence: “I have to say . . . how we lived. Otherwise, our entire generation really will be buried in the abyss of history.” This mythos of selfhood, in which one rises amongst many to speak as if chosen, is defined by the threat of absence. For a country that has perfected its weaponization of silence, even the sheer presence of an individual voice can be radical. Such is how the book makes its statement, a cover unignorably red in the hands, marking itself as necessary by underlining our fear of silence.

Born second to parents that would eventually go on to have four daughters in total, Shen Yang’s invisibility was a chronological certainty. Neither preciously firstborn nor the only excess child of her family, she recalls being first shuffled to the guardianship of doting grandparents, before the arrival of younger and younger sisters inevitably pushed her to the margins. In the tempestuous years of childhood, she moved through the households of extended family and through the dejections of neglect, ostracization, and loneliness. These trials, described in detail, are what compose the majority of her memoirs—episodes threaded with rage, resentment, and yearning scattered against the artless landscape of rural Henan.

It’s difficult to address Shen Yang’s memoir as a simple work of literature. The writing follows the natural misalignments of raw emotion, wavering with indignance and brashness; it feels much like looking at the mirror-image of oneself as a teenager, enraged by worldly injustices as refracted through the prism of selfhood. The aggrieved consciousness of a recklessly emerging identity pervades each recounting of hand-me-down clothing, schoolyard bullying, and corporal punishment. Explosive tantrums—on the part of both children and adults—populate the accounts, balanced out only by equally acrimonious memories of seething, silent hatred. All the players in this vicious game of attachments are intricated in the tenuous balance-game of reluctant, mutual reliances: heartless, cruel, and ugly. Even Shen Yang herself, fragile and explosive, is cast in a dejected shadow. Yet—how can it be otherwise? The text never proclaimed anything other than testimony. I have to say how we lived. The directive of truth-saying, of the voice as a passageway by which history travels, was there from its very beginning. The witness needs not be graceful—only believable. The truth is not the work of poets alone.

The wreckage that politics make out of the human body is most brutally and memorably demonstrated in visceral acts of abjection. So it is that the outside perception of the one-child policy is most evidently marked by the horrors of infanticide, forced sterilisations, and abandonment. The deeper resonances of such overarching regulations, however, are defined by so-called soft pressures: methods of coercion and tradition, which serve to put into overdrive already-innate dedications of compliance, sacrifice, and humility. The birth control programs were only possible in China because of a sprawling, comprehensive system of education that instilled an absolute mandate: overpopulation had brough the country to collapse, and a drastic reduction of the national birth rate was its only salvation. In China, the term “mother country” is not idiomatic. The country is the body that propelled you into existence (one could define it as China’s lack of interest in feigning a separation between church and state). As such, the birth of Shen Yang, and children like her, must be understood as stigmatic, even sinful, in China’s collectivist mentality.

New mothers, in their culmination with the secret fact of life-giving, have spoken of an emotional liberation that likens to nothing else; the world is all of a sudden vast, the self is exponentially increased with newfound paths of tenderness, the smallness of one is engulfed by the multiplicity of two. It is, in the most joyous of accounts, an intimation of eternity. It goes to say, then, that if love is a promise of the future, if love is the euphoria of being alive, children born illegally under China’s population measures had to negotiate for themselves a very different love—for their existence represented only extinction.

When Shen is eventually returned to her parents’ home as a teenager, any potential warmth of an idyllic family life had already been undercut by a decade of estrangement. The violence of neglect, the maddening aggravation—the lack of any traditional bond casts a dense, bitter pall of anger over this new intersection of lives. Frustrated by the profound opposite of a cinematic reconciliation, and having lived her whole life without understanding why she was made to live without love, Shen Yang turns finally to the before in the book’s penultimate chapter. In clean, cursory sketches, she traces the life of the aunt and uncle who raised her: the arduous labour that marked their childhood, the slapdash arranged marriage, the indelible marks left on the psyche by the Cultural Revolution. She arranges the parts, putting them neatly in place, preparing herself to leave it behind.

Feminist writer and scholar Li Xiaojiang stated that though the one-child policy had made undeniably horrific impasses into the lives of women, it is defensible on the grounds that it ensured the next generation of women a different standard of living, choices, and rights—albeit never free from the trauma of their predecessors (an unexceptional consequence of linearly experienced time). Shen Yang presents, in this case, notable evidence of her era; she bridges the denigrations of one generation and the purported successes of another. In the spring of 2021, the Party announced that every couple in China would now be allowed to have three children. The decision, an intervention to counter the negative repercussions of an aging population, was presented as a simple progression of state responsibility on monitoring and balancing long-term population development. In the concluding paragraph, Shen Yang writes: “It is wonderful to survive.” The sense is that she is laying her narrative down to rest in the embers of the page. She is speaking to a world where its villains are no longer perpetuating their livid destructions. The act of creation is one of distancing—one steps back to grip the edges of the frame.

It’s interesting to note that although More Than One Child is a work of translation, only the English version exists in publication. The Chinese original, presumably unpublishable on the mainland, has no presence. To address how the text is determined for an Anglophone audience is to engage with how the literary market inevitably favours foreign texts that promise to reveal something about the countries of their origin, to lend a glimpse into shameful, hidden corners. More Than One Child certainly sets out on that premise, but there is no country to be found in Shen Yang’s prose, only one woman’s cursory initiation of her memories into language.

Language is a habit of representations. The author, by stating in the text that she has not found any other written record of children such as her, has placed herself at the articulating point of where history speaks from the mouth of the individual. “This is not only my story,” she insists. “This book commemorates the childhoods of all of China’s excess-birth children.” By assuming her sovereignty, she has claimed the privilege of speaking on behalf of other “invisible” children, as well as for the cast of family members whose decisions and conditions are cohered in the facts of her life. More Than One Child does not claim to be anything other than individual memoir, but throughout the text it becomes increasingly conspicuous that there is only a single, uniform plane of regard: she, the oppressed, once-quiet other, is looking at the context of her life through what has been done to her. She recognises herself, distinctly, painfully, as victim. The misery of her experiences is elaborated so as to be undeniable, and thus her accomplishments equally pronounced. When I found myself tiring of these gradually repetitious accounts of abuse, and suspicious of the bold characterizations of victory, I berated myself—how can you disparage her writing when she’s gone through so much?

In Matter and Memory, Henri Bergson wrote: “Spirit borrows from matter the perceptions on which it feeds, and restores them to matter in the form of movements which it has stamped with its own freedom.” Sometimes in writing, the hand knows before the mind does—or, the act of fitting thought to language is what steels the idea together from figments. This can, in the most surprising and revelatory of instances, culminate in a text that extends the individual into the universe; it holds the illumed subject to face the light. The utility of a common language is what completes the thought, in front of the world that made it. To criticize the form of writing, as heartless as it seems, is to voice a sense that the language has failed to separate the original from the banal—that it evokes only itself. Trinh T. Minh-ha, in regards to what makes a revolutionary work of art, states that it must “bring about ways of looking and of reflecting that make it impossible to engage in any discussion on a subject . . . without engaging at the same time the question of how . . . it is materialized and how meaning is introduced in the process.” I suspect that the reason More Than One Child failed to move me is because of this sense of self-sufficiency, a closed bracket of meaning.

“In this era, the old things are being swept away, and the new things are being born. But until this historical era reaches its culmination, all certainty will remain an exception,” Eileen Chang once said to us. “In order to confirm our existence, we need to take hold of something real, of something most fundamental, and to that end we seek the help of an ancient memory.” I think Chang would be surprised in our current age—not because what she has been proven wrong, but because the facts she stated are certainly true, and becoming true over and over again to a degree of ever greater speed. The old and the new are interchanging at an unprecedented rate, to the extent that there is no veritable point in which something ends and something begins. The memories that we seek are no longer ancient, but they are memories of yesterday, yesteryear, all the brief accumulations in our brief lives.

There is a bouquet of reasons to read about the life of another: admiration, curiosity, vagrant voyeurism. To read through a lived experience, however, implies a different inquiry: that of putting the pieces together. For the knitted threads that hold our reality and our contemporaneity are so softly glimmering, so multiple, and so tenuous, and our understanding of this fabric so incomplete and subjective, that we are made to sift through the silt and sand of stories for anything that will add force and solidity to the facts of our being. Knowledge, if staggered and isolated from its greater contexts, can only feed the appetites of vague intrigue; a story can only be given into concrete if it can be stitched into that wavering spectrum between one and another, one and one’s country, one and one’s world. Stories have been passages, portals, and escape hatches. Yet in their most momentous occurrences, they are not pathways leading outward and away to an alterity, but a tunnel of excavation that brings us closer to where we already stand.

The dimensions of the one-child policy cannot possibly be reflected within a single person’s lifetime, nor can there ever be a single text that entraps its intricacies within one scheme. Yet one of the promises of autobiography is the vision of enormity in the minute, and the minute in enormity. It implies freedom in the hyphenation between what they felt—what they lived—and what we know. When asked why are you crying, the most alive word in response is that which precedes the reason—the because, for that is what joins question and answer in one. The literature of witness is not the act, but that journey upon the very long landscape of a single because.

On the turbulent, twentieth-century drives of the Chinese country, Han Suyin said: “. . . what is going on in China will remain as a great experiment in human history. And that is what counts.” It’s difficult to cohere this bloodless sentiment with what these experiments have cost—the collapse of humiliations and denigrations perpetually threatening to overwhelm the lives of the present. The stunning feat of Han’s words, however, is their radical suggestion that this happened in China so perhaps the same mistakes would not have to be perpetrated elsewhere—that all of the past is meant to work in this way. Such a legacy of trauma has not kept this stoicism from prevailing in the feminist ideas of contemporary China; it is perhaps symptomatic of the country that built itself on revolution, an act which looks only, dominantly, insistently, forward. The act that swears to itself a future. The place for history in this unrelenting march is to cohere the momentous forces in a direction—to move forward. Suffering is not a setting apart, but a movement towards unity.

Shen Yang is a member of the great, dreaming experiment. I have known many women like her; I have seen her in the mirror. In the ongoing-ness of our selves against the delicate conditions of country, I am looking—as I’m sure she is—at the very many more who will seek to transform themselves from a subject of the state’s inquiries, to a subject of their own. Literature that translates time’s reckless procession into permanence. There are so many more texts to come.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. The chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was published in 2019. The full-length collection, Then Telling Be the Antidote, is forthcoming in 2023. shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: