As war cruelly rages on in Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, one searches for elucidation amidst madness from the country’s writers. As pivotal statements of witness, hope, persistence, and humanity, such texts will undoubtedly go down in history as bright sparks of intelligence and endurance in the dark obfuscations of violence. In Lucky Breaks, Yevgenia Belorusets’s stunning documentation of daily life in eastern Ukraine, the author expertly renders stories of women struggling to reconcile their existence with the broken infrastructure of their country, weaving oratory and textuality with an expert balance of surrealism and sobriety. Testifying simultaneously to Ukraine’s tumultuous history and its uncertain present, Belorusets’s timely work speaks, necessarily, to what survival means, as it is happening.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

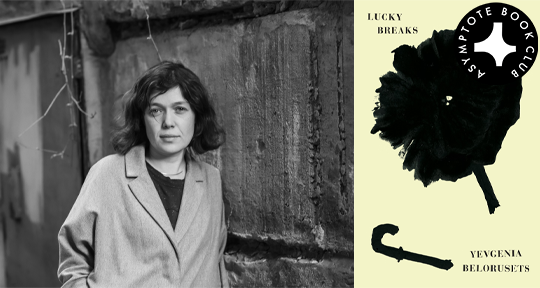

Lucky Breaks by Yevgenia Belorusets, translated from the Russian by Eugene Ostashevsky, New Directions, 2022

More than a month now since Putin’s invasion of Ukraine on February 24, the crisis for Ukrainians continues to have no end in sight. For those of us spectating from afar, the internet has burst into a deluge of breaking news: images of aerial attacks, fleeing citizens, and pulverised buildings circulate and refresh, drawing us into the eye of the conflict. As for the heart, how much of this goes into cultivating real empathy and solidarity, and how much into encouraging a lethargy towards the bits of violence we witness daily through the screen? Literature and translation have risen up almost instinctively to defy this impersonal onslaught: from readings organised by The Guardian to Odessa-born poet Ilya Kaminsky’s advocacy of Ukrainian poetry. Asymptote, too, has launched a new column in support of Ukraine, and as Translation Tuesdays editor, I published Oksana Rosenblum’s translation of Yevhen Pluzhnyk’s “Galileo,” which, while published a week before the invasion, eerily voiced the fate of small states: “I am quiet as grass, even quieter still,/ I am so easily unnoticed.”

The question of what photographs and literature can do in war, I suspect, will not be resolved anytime soon. Amidst this media torrent, however, the daily war diary of Ukrainian photographer and writer Yevgenia Belorusets stands apart for her ability to document the war in both its pedestrian and surreal registers. On the third day, for example, Belorusets writes about meeting a woman in the park who, while carrying two huge shopping bags, admits happily to her: “When there are two of us, I’m less afraid of the artillery.” Two weeks later, she hears two students speak outdoors about what it means to teach as air raid alarms sound. Occasionally, she includes photographs: friends walking their dogs after curfew; a woman holding two bouquets of flowers. Often, the moments she records are ordinary, allowing the mingling of fragile, contradictory truths—that of people living in a simultaneously exceptional and quotidian time and place. Receiving these daily dispatches in my inbox, they come across as disciplined, tender, and urgent.

In Lucky Breaks, Belorusets is the peerless documentarian of her times, a meticulous stitcher of the incongruities that beset contemporary Ukrainian life. Published in the aftermath of the Maidan Revolution and the Donbas War—in which Russian-backed separatists and Ukrainian government forces were engaged in armed conflict—the thirty-three stories elide the overarching histories of war to offer fragmentary, oneiric portraits of individual Ukrainian women: florists, manicurists, factory workers, sisters, refugees, job seekers. Read together, they bring into constellation a denatured psyche of those who live on the margins of gender, class, and geopolitics. Each story runs no more than a few pages in length, incorporating a gamut of different genres from fairytale to reportage. A war diary in its own right, Lucky Breaks defines its author as a composer of her own reality, building it voice by voice with an eclectic cast of storytellers, none of whom take precedence, in a polyphony that resists easy resolution. As she writes in her note before the preface—the only part of the book written originally in Ukrainian rather than Russian—these pages contain “[the] insignificant and small, the accidental, the superfluous, the repressed”; in other words, the losers of history are her main preoccupations.

Suffused as they are with surrealism, one might think of these stories as somehow less urgent than her ongoing diary. Yet, if her ongoing work captures the everyday amidst wartime, Lucky Breaks captures the war that pervades the everyday. Read in conjunction, they demonstrate how the exceptional and the ordinary are merely two threads weaving through the contemporary fabric of peripheral Ukrainian life—one that has destined its people to feel not so much human, but like “soup leftovers.”

This wry observation comes from Sveta Orletz, the titular protagonist of “The Lonely Woman,” who moves from Donetsk (a region swept by pro-Russian separatists since 2014) to Kyiv, only to find herself leading a desiccated and friendless existence: “I’m dying being around them like a bush with no water, like a fireplace with no fire, like a freshly stolen car in the hands of bandits. I’m dying, and I have no one to turn to in the end and say, ‘You were gracious to me!’” Her endless groping for a suitable simile exemplifies how ordinary human sociality turns dysfunctional in Belorusets’s war zone, a place where solitude has the advantage of epistemological certainty, compared with the loneliness of confronting one’s fellow citizens. In a rather more extreme example, Martha from “The Woman Who Fell Sick” is a perverse inversion of the hypochondriac who is “simply bursting with health, so much so that she no longer felt human, although she was holding down three jobs”; she thinks of herself as adjacent to affect, “a clock with a human face, a primitive piece of software, or a cell-phone smiley.”

We could simply describe these circumstances through the framework of trauma, but Belorusets avoids precisely such petrification of her characters by injecting their stories with doses of humour, which Eugene Ostashevsky so expertly conveys in his translation. As such, her characters’ existential plights are better approached as denatured; what is often taken for granted as natural or human—sociality and health, for example—are warped into something only half-recognised, or absurdly shaped. This phenomenon of distortion finds its most moving and painful expression in “The Stars,” where a woman who often finds her memories tangled up with her neighbours’ confesses:

Many people say that the most important thing for us is to have peace. But I’m going to say to you that peace doesn’t matter. Something else matters. But I don’t know what. I just know peace isn’t it. While the war was going on I felt calm, because I was living from one shelling to another. I wasn’t living day by day, but minute by minute and hour by hour.

After this perspective, which seems entirely distorted yet sober, she goes on to detail how the newspaper horoscopes were used by her neighbours to determine whether it was safe to walk outdoors: “We started making calculations so that we may go into town during safe hours. Nothing happened to us—nothing special, nothing terrible—because we always went and came back in the breaks between shooting.” And so a moment often punctuated with terror is soothed by the balm of mysticism, almost fairy tale-like in its naivete. Yet Ostashevsky reminds us that what might appear to Anglophone readers as spurious or fantastical “will be recognised by the readers of the original as beliefs some inhabitants of the former Soviet Union might easily entertain.”

Indeed, what is denatured in Belorusets’s work is not just her characters or interview subjects, but also our understanding of realism as an aesthetic. Rather than read Ostashevsky’s claim as a matter of conveying cultural peculiarities and its untranslatability into new readerships, I prefer to understand it as suggesting that the state of perpetual war under Soviet and Russian imperialism has effectively disfigured what we expect of realism in fiction. Thus, when Belorusets tells the story of a woman who finds herself rooted to a grey granite bench in Independence Square, suddenly unable to walk, we are unable to parse the fact of its actual occurrence from Belorusets’s liberative exercises in fiction. This is similar to the phenomenon of how, at critical junctures—be they personal or historical—we find that everything we say or do serves ulteriorly as an allegory or metaphor for that one overarching event. The woman dismisses the narrator, suggesting that she is “not worth [the journalist’s] time,” since, as a paralysed woman, she is—as she self-consciously refers to herself—a “living monument.” Is this merely the author’s clever comment on the limits of her own ethnographies? Such moments, which undercut the value of the documentarian’s project, do not invoke a playful, postmodern metafictionality so much as they suggest how radical subjectivity—magic, convenience, coincidence, superstition, self-reflexivity—must necessarily be seen to constitute the fabric of reality in a world where normalcy has already been thoroughly punctured and deflated.

Lucky Breaks, apart from being an impressive social document of Ukraine’s recent history, is also a timely re-evaluation of realism and its ethical limits in an age where reality is constantly appropriated for mass circulation. No genre other than photography makes such bold claims on reality, and Belorusets’s two photographic series running through the book—But I Insist: It’s Not Even Yesterday Yet (2017) and War in the Park (2019)—make clear that her project also aims to denaturalise the relationship of text to image, of image to reality. There are empty roads, close-ups of flowers, dilapidated buildings; the realistic language of her photography, in opposition to the fantastical, is emptied of its prime contents—protagonist, drama, or setting. Like the florist in one of her stories who is “convinced that her customers bought not so much flowers as the names of flowers,” there is something beautiful in how Belorusets allows her words to take flight while preventing her photographs from intervening. She understands the danger of the contemporary image—that it appears to work as irrefutable evidence, and her refusal of that certitude in both her fiction and her photography is a clear ethical stand, her own aesthetic revolution.

At the end of this slim but capacious book, there are three consecutive photographs which show a woman inching closer to a man, pulling him closer, finally ending in a passionate kiss. The photographs were taken in 2016, when tensions were escalating in East Ukraine. I think of the narrator’s sister, how “her life—her desires, dreams, and hopes—made sense only so long as [their] city was occupied by armed men, soldiers, unknowns.” I know that somewhere, a war is being fought, two lovers are kissing, and that story is being told. These things, too, appear tender and urgent.

Shawn Hoo is the author of the forthcoming poetry chapbook Of the Florids (Diode Editions, 2022). His translation of Lao She appears in the Journal of Practice, Research and Tangential Activities (PR&TA). He is Translation Tuesdays Editor at Asymptote. Born in Singapore, Shawn is currently based in Shanghai. Find him on Twitter.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: