In the 2000s and 2010s, the great Korean-American poet and translator Don Mee Choi introduced Korean feminist poet Kim Hyesoon to the English-speaking world with a critically acclaimed selection, including Mommy Must Be A Fountain of Feathers (2008), All the Garbage of the World, Unite! (2012), and Autobiography of Death (2019). Choi’s groundbreaking work has inspired the flourishing of English translations of Korean poetry, and a new generation of Korean-American poet-translators, including Stine An, Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello, and E.J. Koh, have built on this foundation by creating translations by Kim Hyesoon’s successors. Among their notable accomplishments include the surreal terrains of Yi Won—published in Cancio-Bello and Koh’s translation of The World’s Lightest Motorcycle (2021)—and the mournful yet witty poems of Yoo Heekyung.

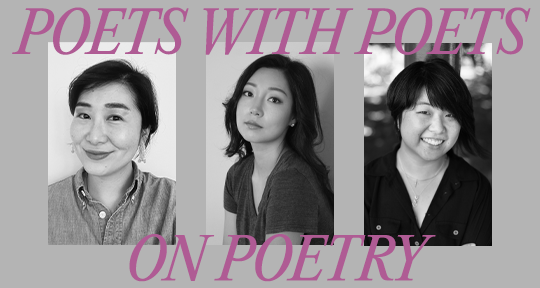

In late February, I had the privilege of speaking with these three exciting new Korean-American voices in the worlds of both poetry and literary translation, where in they radiated love for the translation process, the poets whose work they have been translating, and their mentors. One could feel the warmth in the sisterly connections they recognized between each other. For Asymptote’s inaugural Poets with Poets on Poetry Feature, in which we gather poet-translators from across the world for dialogues about their work, I talked with Stine, Marci, and E.J. about the relationship between their poetry practices and translation, the idea of “rewilding” a translated piece, and their transforming relationships to the Korean language.

Darren Huang (DH): All three of you were initially trained in poetry. Can you talk about your journeys into translation?

Stine An (SA): I was actually interested in getting into translation when I was in undergrad and taking Korean language classes; I thought that translation could be a way to “give back to the motherland,” but I was told by my mentors that you couldn’t have a career in translation. Sawako Nakayasu—a poet, artist, performer, and translator—really encouraged me to explore translation as a way to enrich my own poetry practice. I had the chance to take an amazing translation workshop with her in my final year in the MFA program, in which we were getting the traditional literary translation canon while also learning about experimental translation practices—such as translation as an anti-neocolonial mode and as a way of queering language.

But my intention for going into translation this time around was to have a different relationship to the Korean language. I grew up in a large Korean-American enclave in Atlanta, and for me, Korean language has always been tied to an ethno-nationalist identity. I wanted a more personal relationship to the Korean language as a poet.

DH: E.J., do you want to talk a bit about how you came into translation? I also know this isn’t your first text of translation because your memoir was also an act of translation of your mother’s letters.

E.J. Koh (EK): Translation, to me, feels like a true beginning. I was in a program in New York, sitting in a poetry workshop with a very bad attitude, and my teacher said if you want to write good poetry, write poetry; if you want to write great poetry, translate. That day, I added literary translation to my work.

I would find my mother’s letters, as you mentioned, sit with them in a cabin in the woods in New Hampshire to read them in a new way. When I received the letters at a young age, I would have to read them aloud, then hear myself say the words to understand Korean. Nine years later, I decided this was why I did translation, to be prepared for this moment. And that’s when I began translating these forty-nine letters. It was not just translation as a way to reach back to my mother, it was also understanding what English does to any language, especially Korean. It has a mode of erasure; it writes the words again, as if they were originally in English, which is the way I was taught. I know with my mother’s letters, I didn’t want that to happen. I wanted it to be apparent, even in English, that Korean is there and present—my mother’s voice, the rhythms, the sounds.

When I’m translating Yi Won with Marci, I get to sit down and translate through love. It felt different—this translation as an act of love, because we love each other, this book. We want to reach in to say the things we’ve never seen, love the things we’ve never known. That’s what Yi Won taught me.

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello (MC): I’m so happy to be in conversation with you all because so much of what E.J. and Stine have said resonates with me deeply and makes me feel even more at home. I’m a transracial, transnational adoptee born in South Korea, and raised by white parents from a baby onward. Access to what makes me Korean—aside from the physicality of my body in the world—wasn’t something I had growing up. So I was always really curious about the stories that make people; I’m really interested in the way that we develop our thinking through language, storytelling, music, film, fairy-tales, hymns, and things that feel deeply ancient and connective in community. It always felt like I was trying to come back to Korean in some way, regardless of whether I had any ways of articulating it.

It seems like translators of our generation are trying to get a certain understanding of poetry itself in the act of translation as process. For me, it’s also about access to the original text. I grew up in a deeply religious family, studying how wars were incited over words translated differently across biblical texts and religious groups; it made me think about what the original text said and how people come to those forms.

DH: All of you mentioned how translation is inspiring you as a poet—how have your latest translation projects informed your own poetry?

EK: I mentioned how Yi Won has prepared us to love the things we’ve never known or to see things we’ve never come across, and I think a poem can reveal something that had never been experienced but certainly felt. I love using that idea to prepare myself so whatever I see is strange or different; even if I come across a work that everybody says is unprecedented, I want to state its beauty. Especially now when things seem so ugly, then what is beautiful? This is something poetry allows us to look at again and again.

I do have to say that my English has gotten worse, but I really like that. I don’t know how to make sentences anymore, but I love the undoing that translation has done to my tongue and to my language. Sometimes I’ll slip Korean into my English because it just fits better for me; I’m thinking in a more united sense of what language can be.

MC: Translating Yi Won’s work with E.J., I’ve become a lot more comfortable with uncertainty. The poem’s intention, the discomfort I’m sitting with, the secret I’m trying to parse out and capture in a poem—all these things disappear in my own work. When I first start to translate, I’m so uncertain if I’m capturing or reading a word choice correctly—or making a decision in line with the original. But you have to trust the process through the end; you might actually not realize what’s happening until you finish the piece.

Translation has really created a different relationship with language itself by inciting me to ask: what is meaning, what are the nuances, denotations, and connotations? In poetry, what am I following underneath—the impulse or energy? Do I have the language to articulate this?

SA: I’ve been translating this work for about two years now, and the poet I’m translating has a very different style and poetics from my own. To translate poems I wouldn’t personally write myself, it’s also a way of expanding my own poetic sensibilities. Yoo will sometimes really investigate the meaning of individual words, and the reason I chose to translate him was because I had such an obsession with vocabulary while learning English. I wanted to think about vocabulary in a poet’s world, within a poetic context.

As a poet, translating Yoo always gives me an opportunity to think about what a poem is, what can a poem be, how can a poem work. One of my hesitations in getting into literary translation is that there is such an emphasis on naturalness in the target language. Just based on my relationship to Korean and English, I’ve never felt fully natural in either language; instead of translating fiction or prose, I ended up translating poetry because I felt poetry could be more forgiving or could offer more flexibility.

DH: E.J. and Marci, what is your collaboration process like? Do you form separate versions of the poems and then respond to each other’s? Or do you sit down together from the start to form a single version?

MC: I think E.J. and I both work really independently, privately. The World’s Lightest Motorcycle combined Yi Won’s first and third poetry collections, so we had a lot of text to get through. We would often take batches and each start different poems, then swap.

The thing I love working with E.J. is that there is a lot of trust between us naturally, and I learned a lot from our conversations. The process felt slow, but I’m grateful for that time because it helped me become comfortable with changing my mind. It gave us freedom to follow a particular thread of Yi Won’s poems.

EK: As Marci says, there was a lot of rewilding with the poems. We would get down what the poem is trying to say, but we didn’t get down what it can do to someone experiencing it. We did the trimming, planting, and tending, but the last stage was getting it back to the way it was. That rewilding sensation felt the most pleasant and the easiest with Marci.

Naturally, as a poet, I feel quite feral. When we get to rewild, it’s letting us go back to our feral, rotten, beautiful selves—going back to the language and saying, let’s see what the poem can do if we let it sprout here, overgrow there, and let the language run. I think we’re going to become increasingly wilder as we go down this road.

SA: How did you find your cues for the sense of overgrowing?

EK: I think translation can be interestingly pointed, in that it says: this is what the poem means. But the translation also makes me feel what it’s pointing to. When Marci talks about keeping the energy of the poem, we’re not looking at the words; the words are like the basket for the actual thing—the thing itself isn’t just one word but a network. Staying in those places and being willing to move around and look for the ways the words make new relationships with each other. Letting the words rub up against each other the wrong way, creating friction or mystery. How do you read something with two disparate ideas, and also understand it all at once as unified? Starting at the beginning of a poem, making things feel neater, letting things be wild by the middle or the end.

MC: The editors at Zephyr Press are really champions for being able to have the original text alongside the English. Don Mee’s translation anthology, The Anxiety of Words, which included four Korean women poets was fully bilingual, and her stunning introduction that contextualized their work was important for me as a reader. Otherwise, there’s such a burden placed on the English alone.

SA: The bilingual edition is such a gift because as I’m reading, I can look at the decisions you’re making as translators and also use it as a reference for my own work. Regarding process, I’m still figuring it out. What I like about translation is that there’s a sense of mystery. Sometimes I’ll read the poem before I translate it; other times, I’ll just start from the beginning. The thing that always helps me keep going is my sense of the tone; even if I don’t know the word, I can use the tone to feel my way around the text.

After the first draft, I will let it sit for a while and come back to it. The mentorship I’ve received taught me so much about the importance of getting feedback from other poets or translators or readers you trust. I’ve definitely started seeing translation as a very collaborative process with the poet you’re translating, but also with other translators who are very generous to read and think about translation with you.

MC: Stine, have you been able to connect with your poet? Are you able to talk to your poet?

SA: Yes. I’ve been in touch with Yoo over email, maybe three or four over the course of two years. I’ve gotten to know other Korean literary translators; there’s a lovely sense of this larger Korean poetry community.

MC: I’m grateful that our poet is alive and able to provide some context for the translation process and answer our questions, and I agree there is something wonderful about seeing the connections between Korean poets and the Korean-American poetry translation community. Yi Won sent us a couple of recordings of her reading her poems, and it completely changed my perception of her work, compared to just having read it on the page. One of the things she said in our virtual launch was she found our translations to be new poems rather than translations—an excavation of a poem within a poem.

EK: At our launch event, it was surprising to hear Yi Won talk about the book after receiving it. It seemed like she had such wonderful grace about Marci and I being Korean-American poets; she was very thoughtful about that, saying Korean-American women poets translating Korean poetry is something to be gracious about, that there is more that is brought to Korean poetry by that process alone.

SA: The encouragement and positive feedback is so meaningful and valuable. For me, it was important having poets or translators whose work I respect and admire giving me the encouragement to continue.

The gift of someone’s time and feedback and getting to learn how they approach their art—I found that to be amazing. With mentorship, getting that fuel to keep on going.

MC: What you’re saying really resonates with me about that encouragement to keep going both from people who’ve been doing it for a long time or colleagues who are doing it with you. We’re always thinking about the people who came before, opening the doors, and thinking about permission to move forward. Sometimes you just need someone to say at the right time, “Keep going.” It also is a wonderful thing that the work all of us are doing is for the next generation; we’re contributing in some small way and opening doors for others, too.

E.J., especially, always brings it back to love. I’m thinking about war and power and anticolonialism. But E.J. says translation is an act of love. Having that kind of collaboration and voice of a sister poet is so important.

SA: What brought me to poetry in the first place is its provision of an arena for experiencing delight and joy, for pursuing curiosity and pleasure. The same with translation—when I’m having a hard time translating something, it’s always helpful to think about the places to find joy and pleasure within the text.

DH: E.J. brought up a really interesting point—how Yi Won was excited about Korean-Americans translating and looking back to Korean poetry. Can you talk about how your experiences with these works have transformed your relationship to Korea and the Korean language?

SA: When I write about language, I get very emotional. There’s still a lot that’s unprocessed. It was so easy for me to be stuck in the traumas around language. The context in which I maintained Korean language—part of it was for survival, translating for my family. I was placed in the role of an interpreter without training. There was always a sense that if I don’t continue maintaining this language, I’m not going to be able to communicate with my loved ones. There’s also the sadness of realizing that the Korean learnt in a college classroom wasn’t necessarily the Korean that would help me communicate with my family members.

There’s so much pressure with Korean language being tied to Korean identity, without addressing any of the politics around it. Don Mee’s pamphlet from Ugly Duckling Presse, Translation is a Mode=Translation is an Anti-neocolonial Mode, changed how I saw translation for myself. As I’ve started doing literary translation, it’s provided an opening to have a closer and more personal relationship with Korean, outside of the pressure of maintaining identity or agenda. There’s more joy and pleasure in my relationship with the Korean language.

EK: The relationship between the Korean-American poet and native Korean poetry is complicated and interesting. There’s a sense of being a perpetual outsider, outside the dominant historical narrative which ends on that land. Once you leave it as an immigrant or adoptee—my parents left for Korea and I didn’t reunite until well into my adulthood. Those narratives are not as visible within history, and that’s why I think it means so much to bridge the history across Korean-American and Korean poets. That’s a way of crossing the Pacific, a way of describing continuance. There’s so much grief and joy to be known if we can keep telling those stories—translating is a part of that.

MC: I asked E.J. once if she thought I had permission to write poetry about a specific topic connected to Korean history and culture. And she wrote a letter back, saying, “You’re 100% Korean and 100% American, and that gives you the right.” It’s a letter I carried with me for maybe five years after because there was something about how simply she equated that. I’ve spent a lot of time trying to figure out my relationship to Korea as a transracial adoptee, feeling caught between two countries and looking one way and not being able to speak the language. What does belonging and absence of language have to do with my identity?

This process has taught me that I am something new, as that the translations are something new. And Korean-Americans are new. We’re all of it and by extension, more than what we think we are. And the poems themselves are more than what I can give them because they’re from an original text and they have Yi Won and E.J. and me in them, all of our hopes and intentions toward the reader.

I remember E.J. and I talking about Korean-American literature and she said, “Look how far we’ve come but look how far we have to go.” Looking at our book of poems in translation, I feel like I am at that seam between the English and Korean, looking at both languages simultaneously. I feel how far I’ve come, but how far I have to go. Drawing delight out of the darkness is something I’m excited to keep learning to do, because of what all this has taught me.

Stine An is a poet, literary translator, and performer, based in New York City. Her work has appeared in Black Warrior Review, Pleiades, Waxwing, World Literature Today, and elsewhere, and she is working on a translation of Yoo Heekyung’s Oneul achim daneo. She holds an MFA in literary arts from Brown University and has received fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center and the American Literary Translators Association.

E.J. Koh is the author of the memoir The Magical Language of Others, winner of the Washington State Book and Association for Asian American Studies Book Awards, the poetry collection A Lesser Love, and co-translator of Yi Won’s The World’s Lightest Motorcycle. Her poems, translations, and stories have appeared in Los Angeles Review of Books, POETRY, and World Literature Today, among others. She earned her MFA in literary translation and creative writing from Columbia University, and is a candidate at the Ph.D. program at the University of Washington in Seattle. She is a recipient of MacDowell and Kundiman fellowships.

Marci Calabretta Cancio-Bello is the author of Hour of the Ox (2016), which won the 2015 Donald Hall Prize for Poetry, and co-translator of Yi Won’s The World’s Lightest Motorcycle. She has received poetry fellowships from several organizations, and her work has appeared in The Georgia Review, Kenyon Review Online, The New York Times, The Sun, and more. She is co-director for the PEN America Miami/South Florida Chapter, and is a program coordinator for Miami Book Fair.

Darren Huang is a writer of fiction and criticism based in New York. He is a blog editor at Asymptote and an editor at Full Stop. His work has been published in Bookforum, Los Angeles Review of Books, Words Without Borders, Gathering of the Tribes, Kenyon Review, and other publications.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: