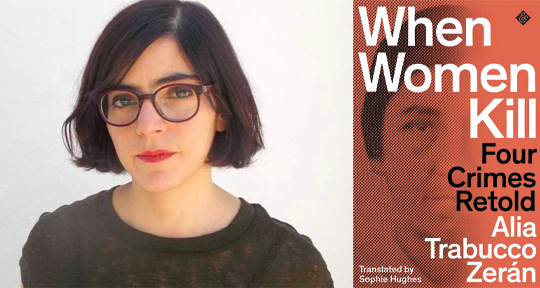

When Women Kill: Four Crimes Retold by Alia Trabucco Zerán, translated from the Spanish by Sophie Hughes, And Other Stories, 2022

Could such bloody murders really have been committed by women? Did they owe their homicidal violence to advances in feminism?

Alia Trabucco Zerán has been training herself to suspect—as if it were an art form. It is this honed ability for distrust, combined with her background in law, that brings her close to the four women at the center of When Women Kill. In her debut novel, The Remainder (shortlisted for the 2019 Booker International), Trabucco Zerán told the story of Iquela and Felipe, who undertake a road trip to help their family friend Paloma collect and bury her late mother’s body. The lives of the trio are bound with the loss and terror of Pinochet’s rise to power, and as the sky darkens to the color of ash, they too dream of corpses, sinking into hazy memories. The Remainder sealed its author as one of Chile’s most recognized and poignant debut novelists, and central to its story is the same uneasiness of forgetting that pervades When Women Kill; what is true, in a lawful sense, is curled and uncurled in this text, making it one of the more incisive intersectional feminist analyses of myth and murder.

Trabucco Zerán begins her book by explaining why she undertook this study, claiming that a woman who kills is “outside both the codified laws and the cultural laws that define and regulate femininity.” Scavenging through multiple archives, court documents, films, and plays, she reconstructs the history of Corina Rojas, Rosa Faúndez, Carolina Geel, and Teresa Alfaro—four high-profile Chilean murderers of the twentieth century. She is unconcerned with learning about the motivations behind the acts; instead, the book serves as an account to remember and discern the women who commit crimes, who have expressed their rage.

The first crime takes place in 1916; Corina Rojas, an upper-class housewife, hires a hitman to murder her husband. Her story—not unlike that of many women who are trapped in loveless marriages with unfaithful husbands—begins when she meets her piano teacher. She falls in love with him, finally seeing an escape from the mental agony of her drab marriage. However, because divorce is illegal, she has no way out except widowhood. According to Chilean criminal law at the time, adultery is a crime (until 1994), and an unfaithful woman can be sentenced up to five years in prison, as opposed to a man who “has to keep the concubine within the conjugal home.”

By looking at particular instances of gender bias in law, Trabucco Zerán notes the level to which a woman’s honor is dependent on her sexual behavior. Rojas’s affair is seen as transgressing a sacred tenet of womanhood, and she is judged harshly by court and media alike, eventually sentenced to death. To add to her defiance of cultural strictures, the man she has an affair with is a Bolivian immigrant. Her crime is deemed unforgivable. Corina Rojas’s story becomes a sensation in both the art world and crime world, twisted into hyperboles and bound to the myths of other women in history associated with crimes of passion. She is dubbed a Medea, Medusa, La Quintrala, or Lucrezia Borgia. She, like other women killers, comes to be cast either as a femme fatale or a meek, despairing woman.

In contrast to Rojas stands Teresa Alfaro, a maid and nanny who poisoned her employers’ three kids. In writing her story, Trabucco Zerán searches for language free of condescension, thinking through the invisibility of housekeeping staff in Chile. By incorporating within the text her own diary entries, written in first-person and present tense, the author lays out her struggles to collect information—reading from smudged out, blotted documents, consulting kind librarians, and spending relentless hours indoors—and opens an insular look at the writing of non-fiction to morph the author into a character in her own book. Outside of her well-researched and stable authorial voice, her personal notes portray her as desperately in search for answers. Similar to The Remainder, this intimate perspective expresses her own dissatisfaction as she undertakes the momentous journey to recover hazy memories and unpack a fraught history.

Trabucco Zerán’s account of Alfaro first appeared in the 2019 issue of Words Without Borders under the title “Behind Closed Doors: Chilean Stories of Domestic Life.” Because Alfaro is an angry, lower-class employee, her anger—just like her work—is obscured. She has no right to become a mother or wife. There are no representations of her to be found in the realms of art or media, nor are there long-drawn out sessions in court. She is instantly found guilty, and the world seeks to do away with her altogether. Here, the writing gives unfettered space to her own anger: “I want my words and those of the law to meet on the page and touch, at first barely brushing, then rubbing up against each slightly, and by the end, as the story reaches its climax, for them to bash against each other, clashing fiercely, violently, until sparks fly.”

When the law fails to provide a full spectrum of answers, Trabucco Zerán seeks out Foucault, Julia Kristeva, Sara Ahmed, Judith Butler, and many others. She looks at the possibilities of womanhood from law and literature alike, and Alfaro’s history is pieced together sensitively, revealing how her employers restricted and demeaned her. Among daily humiliations, she was forced to break off her relationship with a married man and abort three children (although abortion is illegal in Chile). If Alfaro refused to comply, she would be left without a job, and reemployed only once she agreed to their demands. During the court proceedings, however, the magistrate does not look at resentment as a motive, but instead adds her abortions and affair as transgressions against womanhood; it is Trabucco Zerán who deliberates the impact of these restrictions. Alfaro poisons the three children under her care by putting strychnine in their milk bottle, but it is the children’s actual mother who feeds it to them. In this, Alfaro strips her employer of motherhood, seemingly in revenge for her forced abortions. Here, the author calls upon Kristeva:

Perhaps unintentionally, the press seemed to echo this role reversal between the two women with their peculiar choice of editorial photographs. In them it is Teresa Alfaro, not Magaly Ramírez, who cries inconsolably. . . The fake mother, the impostor, gives the lead performance as the mater dolorosa. Her body is the site of what the critic Julia Kristeva understands to be the two quintessential symbols of motherhood: milk and tears. Alfaro not only strips Magaly Ramírez of her role as mother within the home, but she replaces her as the suffering mother in the eyes of the public.

Similarly, she wonders about Carolina Geel, who in the 1950s represented the image of the emancipated woman: successful writer, twice divorced. Geel’s ambiguity on why she murdered her boyfriend in a restaurant full of journalists is what pushed Trabucco Zerán into writing this book. Through the spectacle of this crime and the events that follow, Trabucco Zerán unpacks the history of women with mental illness—how hysteria and madness ultimately both condemns and rescues them. Working with Foucault’s theory of madness and judgment, she writes: “With her ambiguity and silence, Geel refuses to show remorse; in the process, she also refuses to recognize the law that punishes her.”

Geel is deemed “abnormal,” but when she writes a story about women and lesbianism in correctional facilities, she is seen as opportunistic. Trabucco Zerán notes that women writers in Chile in the 1950s were frowned upon, citing that “Gabriela Mistral would have to win the Nobel Prize in Literature before she would be recognized in her own country with Chile’s National Prize for Literature.” In this, she equates the act of writing with taking up arms. That Geel can write and continues to apologetically write makes her answerable; she is in control of her own narrative. Similarly, Rosa Faúndez, a woman who kills her husband with her bare hands, dismembers his body, and disposes off the fragments in different parts of the city, refuses to show any remorse despite being deemed cruel or unfeminine. Having been written off as unworthy of documentation, this defiant retelling of Faúndez’s tale reveals the manufactured idea of femininity. By bringing these unexamined tales to light, the hybrid nature of When Women Kill is persuasive in its insistence on looking deeper, echoing the fluctuations in the perceptions of womanhood.

Both of Trabucco Zerán’s books have been translated by the exceptionally talented Sophie Hughes, a former editor-at-large of Asymptote. In her translator’s note, she speaks of the transgressive power of the book’s title:

The Spanish word homicida, meaning “killer” or “murderer,” is rare in that, as a general rule, most masculine nouns in Spanish end in “o” not “a.” Thus, a group of male or mostly male homicidas are only identifiable as such by the gendered definite pronoun “los”: Los homicidas, “the [male] killers.” Trabucco Zerán’s use of the female pronoun is therefore a subtle tweak. “Las homicidas”: switch off for a millisecond and you could very well miss it, or rather them, “the women killers.”

Similar to the essay Deborah Smith wrote on translating Han Kang’s Human Acts, Hughes, too, uses the translation of the title as a way of pointing at the larger picture of intersectional investigations. Through her spectacular translation, the reader experiences the text’s shapeshifting nature, being pulled into the dazzling vulnerability of the diary entries then taken back to the disciplined and necessary task of understanding women behind and beyond the sensationalist portrayal of their acts. In looking at disobedient women, the book dismisses “the lawyer’s red pen” and the “narrow confines” of law. Weaving together multiple literary styles and a wide range of voices, When Women Kill constantly remolds and blends genres, culminating in an irresistibly compelling read.

Suhasini Patni is a freelance writer based in Jaipur and Delhi.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: