In Auður Jónsdóttir’s award-winning Quake, there is no such thing as absolute clarity. Depicting the aftermath of memory loss, this novel of mystery and recovery is a subversion of certainties, a blurring of the demarcations between fact and fiction, self and other, past and present. By blowing the pieces of identity apart, Jónsdóttir is asking the ever-pervasive and urgent questions: where does one start, where does one end, and what happens amidst it all, in the in-between?

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

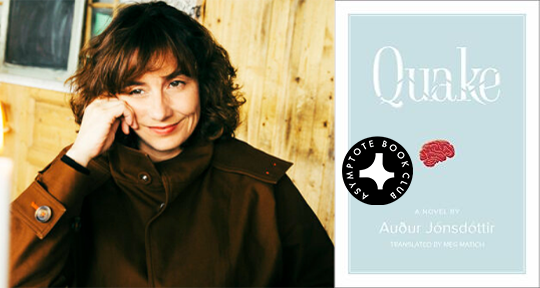

Quake by Auður Jónsdóttir, translated from the Icelandic by Meg Matich, Dottir Press, 2022

“Let me be frank . . . There’s something to be gained from having another person look at your life.” So goes the advice that Saga, the narrator of Auður Jónsdóttir’s Quake, receives from her older sister Jóhanna as the former contemplates the reasons behind her divorce. But are other people—and the narratives they create about you—always reliable? Are they always useful? And what if, faced with the prospect of rebuilding your identity, all you had to go on was what other people remember, or think they know about you?

Saga, a thirty-something divorced woman and mother to a three-year-old boy, is attempting to piece together her life story following a set of violent seizures. The condition has left her mind fractured, and though the gaps newly carved into her memory are few, they make it hard for her to establish a cohesive narrative about her life and her sense of self. “I can’t seem to shake the feeling that I’m an alien who woke up on the kitchen floor of my family’s house one day and convinced them I was one of them,” Saga says, attempting to position herself within her seemingly normal nuclear family. Such themes of alienation and identity are at the core of Quake, which tackles these questions with scalpel precision but also a sense of tenderness, singing through Meg Matich’s translation.

Betrayed by her body and her mind, Saga has to rely on those surrounding her to map the contours of her existence, to fill the lapses in her history. This journey is populated by a cast of characters as demanding as they are unreliable and cryptic—an ex-husband, irritated by her concerns about their frail son, choosing his own writing career above all else; a mother with a tendency to belittle and disappear at the most inopportune moments; and Jóhanna, an overbearing older sister who sees herself as the responsible one in the family.

However unrelentingly anxious Saga is about her mind and health—and what it means for her and her son on a practical level—she finds the time (and perhaps a new urgency) to contemplate the nature of memory. At first, she has a cavalier attitude towards the seemingly symbiotic relationship between one’s own sense of self and the influence of others: “My understanding of the world is, in large part, result of the fictions of others. It’s confirmation that writing has a definite value.” However, the longer she goes without her memory, the more that positive outlook begins to shatter. As she tries to pry, from her friends and family, the most salient details of recent events (What does she do for a living? Why was her son sick? Why did she leave her husband?), Saga begins to realize that she is not simply dependent on them as sources of facts or objective knowledge; she is forced to contend with their interpretations of her life. While her loved ones can relay events or snapshots of conversations to her, they can’t remind her of how she used to feel at any given point in time.

My closest friends remind me of a hall of mirrors: their eyes show me some of who I am, but my reflection is distorted. They don’t all see the same person.

Beyond this idea of a splintered self, resulting partially from the contentions between perspectives, Jónsdóttir presents a compelling theory about selfhood that has a post-humanist flair. When Saga realizes that she can’t rely entirely on herself or even others, she looks for clues elsewhere. In fact, she turns to her laptop—what she calls her “back up brain”—to get a purer sense of who she is. Her laptop contains her correspondence, social media pages, and even a short journal which, while limited and disparate, together seem capable of an objectivity that she is unable to find in human definition—with all its tendencies towards interpretation. I am not sure if Jónsdóttir meant to consciously point us in this direction, but the reflexivity with which Saga turns to her laptop, as well as the answers that she finds there, reminds me of the extended-mind theory of British philosopher Andy Clark. In his work, Clark argues that the tools that we use to think and communicate (even if just to ourselves), are extensions of our minds. They are tools, no less real than our fleshy brains, through which thought and memory, and thus a self, are created.

But of course, her laptop is just one of many avenues of remembrance that Saga pursues to get herself back. Along the way, she stumbles upon the realization of how truly precarious the body and the human mind are. Unable to count on the stability of one’s self, there can be no control, only the naïve illusion of control, further complicated by the fact that there is no singular, independent human mind; as memories seep into one another, from body to body, perhaps we aren’t as disparate and separate as we would like to believe. There is a particular poignant moment in the novel when Jóhanna quite literally invites Saga into an old memory of hers, and they experience it together, as if they shared the same mind.

We are stranded in Jóhanna’s memory, our memory. I fight tooth and nail. I don’t dispute her version of events, but it’s a quagmire; the further I slog, the deeper I seem to sink until I am submerged. I will die if I cannot get out . . . But I can’t escape the regret in her eyes. She remembers what I survived, she remembers for me, she suffered for me.

For all the philosophical quandaries that Quake raises, the book never feels contrived or solipsistic. In Matich’s English translation, Saga’s shifting understanding of herself is rendered in a language that is straightforward yet poetic, for Jónsdóttir understands that human life is inherently imbued with poetry. Furthermore, in keeping with the ethos of the self as a communal fabrication, Saga’s knowledge and ideas are challenged and expanded in conversations with others: her doctors, her family, and even a couple of teenagers who share with her the dubious results of their internet research on epilepsy. This reliance on conversation rather than simple monologue make Quake an engrossing read, just as they serve a larger aesthetic and philosophical purpose.

In the understanding that there can be no core, individual self, one is choosing to experience identity as a series of continuously changing and collaborative processes. In the most optimistic of viewpoints, this perhaps indicates that people are truly capable of change—that no one can be defined by their worst moments, an understanding that Saga comes to after her quest leads her to uncover a devastating family secret.

My parents know how to seek shelter into one another, even after they’ve cut such deep wounds in one another that they will never heal. They don’t trust the outside world to understand that a good man . . . can’t be judged based on a single period in his life. They sentence themselves to silence because uncareful words might splinter their existence.

Of course, this call to radical empathy is easier understood than applied. For all the porosity of selfhood, Quake also shows that people are deeply attached to the idea of the self as unique and self-contained. Thus, our own beliefs about larger moral truths, and our understanding of our experiences as unique and unprecedented, ultimately fracture our ability to build deeper connections with others. In this novel, Jónsdóttir posits that this singularity is a carefully constructed illusion. After all, as Saga eventually comes to realize, she isn’t the only alien in the family. They all are.

Barbara Halla is the criticism editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in history from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: