In this week’s selection of translated literature, we present Hassouna Mosbahi’s expansive, dreaming portrait of Tunisia through the recollections of one man’s life, as well as Nataliya Meshchaninova’s precise, cinematic cult classic of a young girl carving her own way through abuse and neglect in post-Soviet Russia. Read on for our editors’ takes on these extraordinary titles.

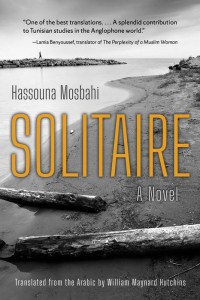

Solitaire by Hassouna Mosbahi, translated from the Arabic by William Maynard Hutchins, Syracuse University Press, 2022

Review by Alex Tan, Assistant Editor

The essential core. The innermost heart. The pupil of the eye. The central pearl of the necklace.

These are epithets lifted from a tenth-century anthology of poetry and artistic prose by the literary connoisseur Abu Mansur al-Tha’alibi—a privileged arbiter of what counted as the era’s innermost heart. Determined to immortalise the remarkable cultural efflorescence of his contemporary Arab-Islamic world, al-Tha’alibi took upon himself the task of gleaning the anecdotes, biographies, epigrams, and panegyrics he deemed exemplary of his epoch: “sift[ing] our enormous rubbish heaps for our tiny pearls”, as Virginia Woolf once wrote.

Not for nothing did al-Tha’alibi name his compilation Yatimat al-Dahr fi Mahasin Ahl al’-Asr: “The Unique Pearl Concerning the Elegant Achievements of Contemporary People.” From the inheritance of this opulent work, the Tunisian writer Hassouna Mosbahi drew inspiration for his own dazzling, shape-shifting novel Yatim al-Dahr—cleverly rendered in English by William Maynard Hutchins as Solitaire. Hutchins contextualises the title in his helpful preface, explaining that “yatimat” refers to both a “unique, precious pearl” and “fate’s orphan.” “Solitaire” reflects these prismatic valences.

Solitaire, also, is a game one plays with oneself; Mosbahi’s book, in many ways, is a puzzle with no straightforward answers. It is encyclopaedic and uneven and oblique. Stories proliferate, nestled within other stories, structurally echoing the classic Thousand and One Nights.

On a first reading, it is easy to sink into the sediment of the novel’s non-linear chronology, before being pulled abruptly out of the seductive illusion and back onto the newly destabilised present. Mosbahi’s work dissolves temporal barriers, saturating the present with echoes of the past. It feels vertiginous to remember that all the action spans a single day, kaleidoscoped through the mind of the eponymous orphan-protagonist Yunus and taking place mostly along the coast, at the threshold of sea and sand. Language arrives on the page like slips of paper curled up in glass bottles: Sufi prayers, journal entries, newspaper articles, quotations of verse, orally transmitted tales, autobiographical monologues—shored up in their rawness. Digressions expand, often without warning, to constitute entire chapters. Hutchins’ translation captures these tonal shifts impeccably.

In the novel’s present, Yunus is celebrating his sixtieth birthday. Presuming that this date is 2012 (when the book was published in Arabic), it also marks the sixtieth anniversary of the beginning of Tunisia’s liberation from colonial occupation. Thus, Yunus’s age becomes more than mere figure. In the coastal city Nabeul, he assembles a motley crew of friends, and together, they cast a retrospective glance over his life. Tunisia itself is not spared from the patina of age (Nabeul is referred to by its “antique name,” Neapolis), and as such, Yunus’s memories demand to be read equally as a story of his country, wounded and floundering beneath the weight of identity crises and authoritarian rule. That frame imbues with gravity all the childhood fascinations, intellectual obsessions, creative failures, erotic exploits, and conjugal tribulations that, in their meandering totality, have landed Yunus in his current position as professor of French literature.

As writer manqué, Yunus is drawn like an “enthralled lover” to the traditions of his European colonisers. He repeatedly measures himself against them, only to come up short. Where Flaubert narrates in a “terse, lyrical language,” Yunus can only regard his own work as “self-absorbed, apprehensive, and hesitant,” or “lusterless imitations of books he read.” Paralysed by his inner critic, Yunus never attempts to publish, and adopts the pseudonym “Yatim al-Dahr” as if in need of an alibi. The fact that he lives in a country where writing is “a curse and a trial” hardly helps matters.

In his impotence, Yunus perhaps resembles—or wants to resemble—nothing so much as al-Tha’alibi’s Yatimat al-Dahr. If he is unable to piece together the fragments of his life and his epoch, he will leave them with their fractures intact—an archipelago, orphaned. Virginia Woolf’s diagnosis of her own modernity resonates here: “Much of what is best in contemporary work has the appearance of being noted under pressure, taken down in a bleak shorthand which preserves with astonishing brilliance the movements and expressions of the figures as they pass across the screen.” Though the constellation of his history, Yunus has metamorphosed into a loose hodgepodge of text that hopes, however vainly, to recuperate a semblance of lost meaning.

Yunus’s unmooring—as semantic as it is existential—distils the plight of an entire generation, as his friend Béchir points out:

Listen, Yunus, my dear. We, who were born in the middle of the last century, have entered the twenty-first century as orphans in every sense of the word. We have entered it with our hands and feet flayed, our powers exhausted by the lengthy distances we have traversed during what now seems an Empty Spring, when our dreams and hopes have been demolished and buried alive before our eyes, with no mercy or compassion.

Another friend, Si al-Tahir, comments elegiacally later on: “The homeland was our first and last true love.” Unrequited in romance, they find themselves disillusioned by the failures of revolution; ideals can no longer bear the weight of their abuse. Yanked from one regime to another, from Habib Bourguiba’s consolidation of power to Ben Ali’s bloodless coup d’état, Tunisia has turned unrecognisable even to “those who had lived there all their lives.” Even religion has lost its unifying potency, as Yunus and his set lament what Islam used to be—“without any posturing or pretense.” These days, the deafening call to prayer interpellates the daily, “as if calling [them] to a war that is about to erupt.”

Mosbahi details with great care—sometimes at the expense of subtlety—the hypocrisy, rapacity, and rampant clientelism of the Tunisian ruling class, documenting the perils of living in a climate where “despair, frustration, tribulations, and massacres [are] daily events.” An extended section on Tunisia’s First Lady Leïla Ben Ali (though never directly named) is particularly entertaining for its svelte depiction of her chameleonic social manipulations and meteoric rise through the echelons of power. It makes sense that Mosbahi dedicates the book in part to his country, in the hope that it will “regain / ‘Sense and meaning.’” We might read Solitaire as a love letter all too cognisant of its recipient’s failings—conceived from a necessary distance and all the truer for it. We might also read it as a book addressed to the elusiveness of belonging. Mosbahi lived, after all, in Munich for several decades in exile, and his literature takes from such disassociations to form an opalescent body in which questions of attachment mingle:

I closed my eyes, wishing to flee from my black soul to another world. At some moment, a different vision of my country dawned on me—not the vague, gloomy one I had grown accustomed to harboring as an expatriate. It came to me with the radiant light of a Mediterranean morning on the beach at Les Grottes in Bizerte, green and fragrant like the vineyards and the orchards of figs and almonds in the spring at Raf Raf, dreamy like sunset in the oases of el-Djerid, and white and blue like the houses in Sidi Bou Said.

How many ways are there to be an orphan? What does it mean to be an orphan of dahr, variously translated as “time,” “fate,” “destiny”? Yunus’s many complexes come to mirror, in miniature, the collective anxieties of Tunisia, seeking a foothold from which to know itself—a history to learn anew.

It is something of an irony, indeed, that Yunus characterises himself by his rootlessness while owing his nom de plume to a key litterateur of Arabic belles-lettres. Alongside the guiding spirit of al-Tha’alibi, other admired figures permeate his ruminations: the modern poet Adonis, who believed that “the essence of poetry is consciousness and political expertise”; the ninth-century polymath al-Jahiz, who “devoted his life to writing and reading”; the eleventh-century Andalusian beggar-king al Mu’tamid, whose “love for life, beauty, and poetry” tided him through the pain of his exile. Rather than disavowing parentage, Yunus seems to me to be imagining—however fancifully—a parallel genealogy: one that would bind him, in his tortured solitude, to all these untimely figures suspended in the thickness of their epochs. If, as he thinks, “no true literature can exist in the shadow of censorship,” Yunus dreams rather of a literature to come, in which words can again coruscate. We may not live to see that day—but that vision alone might be, for Mosbahi, the unique pearl of our age.

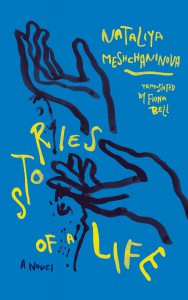

Stories of a Life by Nataliya Meshchaninova, translated from the Russian by Fiona Bell, Deep Vellum, 2022

Review by Andrea Blatz, Blog Copyeditor

In Stories of a Life, Nataliya Meshchaninova blurs the line between fiction and reality. The life in question is that of Natasha—the author’s fictionalized self—and the narrative traces her coming of age in the late nineties of Russia, a story of enduring and surviving sexual abuse. Written in raw and straightforward language, Meshchaninova brusquely chooses truth over gentility, and translator Fiona Bell’s artful translation renders its ruthlessness with fluidity and poetry. Originally written as a series of Facebook posts before being released as a book, the novelist’s filmmaking history comes through in the scene-by-scene portrayal of Natasha’s life, focusing on various themes to coalesce in the portrait of an impossible childhood, in which a constant struggle prefaces her finally finding the strength to escape.

One lesson Natasha learned early on is the importance of lying to protect herself and others; in this way, she creates her own reality. Her diary entries are filled with lies about who she is and what she looks like: “‘My love overwhelms me’ (no need to mention that it was unrequited). ‘My beloved is a handsome man with sensual lips. Yesterday, as I walked through the park on my way home from practice’ (no need to say what sport, it lent some mystery).” Rather than allowing people access into what’s really going on in her life—a life where she is constantly on the lookout for betrayal, especially of men looking to take advantage of her—she portrays “[a]n alternate reality, a sweet dream, not a word of harsh truth.”

For me, the most striking aspect was how alone the women are, lacking any sense of solidarity or understanding—even between mothers, other relatives, and close friends. Natasha hides the abuse and eventual rape by her stepfather, Uncle Sasha, believing it would literally kill her mother if she knew: “Because if she finds out, or even guesses, she’ll die on the spot. I had no doubt about it. Because that’s something mothers can never survive. They just can’t.” Imagine the blow, then, when she learns her mother knew all along and simply never said anything, or ever tried to stop it:

[My aunt] and my mother had a simple explanation: the whole time Uncle Sasha and my mother lived together, I, like fucking Lolita, was seducing Uncle Sasha and he was cheating on my mother with me.

I wasn’t particularly surprised, except by one thing. One thing that completely invalidated my sacrifice. My many years of silence. Just like that, my great idea of protecting my mother’s heart was shot to hell.

My mom knew.

From the start. Since I was nine.

And she survived.

My mother’s a survivor, all right.

She survived something mothers are never supposed to.

While Uncle Sasha “murdered [her] childhood,” the second and equally serious tragedy is the denigration and blame the women in her life load onto Natasha. In this heartbreaking realization, Natasha realizes that not only is there no sense of empathy between her and these women, but worse, they are complicit. Natasha has to be self-reliant because, in her world, there is no one she can trust. This betrayal underlines her need to lie, since no one believes her—or cares—when she tells the truth.

After years of being taken advantage of by her stepfather, Natasha eventually realizes that she has become bigger and stronger than him. At this point, instead of quietly giving in as usual, she pushes him away and laughs “[a]t him. At his polio. At his impotence. At his shrimpy body. At his temper. At his wormy wretchedness. At his lust and at his penis.” Armed with her newfound power, her laughter finally makes him feel impotent—giving him a taste of his own medicine—and frees herself, realizing she no longer has to submit to what he or her mother desire of her.

Natasha eventually escapes to Moscow, where, despite being alone and perhaps vulnerable, she is free from the fear of men marking her as “easy,” or Uncle Sasha creeping into her bed. In Moscow, she becomes her own person, forges her own path, and eventually becomes a film director—Meschaninova’s autobiographical detail. The capital is also where Natasha discovers the power of writing. One night, after penning the murder of Uncle Sasha with a screwdriver, she finds out that those same events had actually transpired, imbuing her with a sense of power she had never known before. Extra-diegetically as well, Meshchaninova’s forceful writing helped bring awareness to the intricacies and silences of Russian women, and Stories of a Life has become fundamental to the #MeToo movement in the country. In this way, the line between Natasha and Meshchaninova continues to blur, as both find empowerment through the written word.

Even in Moscow—however separated by time and distance—the relationship between Natasha and her mother remains complex, a painful and convoluted blend of hatred and love. When her mother visits, Natasha feels obligated to play host, despite continual struggles to maintain control and calm her rage:

I love you.

I say this to myself once every minute, so I don’t turn into a monster. I say these words—“I love you”—as if to absolve myself a little. I try to balance the scales unconsciously with these words.

“I love you, Mom.” It’s a spell that keeps me from turning into a werewolf when the sun goes down.

These words act to induce pleasant memories from her childhood, allowing her to tolerate her mother a little while longer. As she pretends to want more time with her mother, Natasha soon comes to realize that neither of them is willing to put in the effort to maintain a relationship, or even the façade of a relationship. They are both, in a way, free, having moved on and created lives outside of one another.

Though Stories of a Life provides an unflinching look at the distressing and shocking variances of abuse, the novel is nevertheless one that traces a journey of fortitude—how one can move on after the experience of trauma, and all the complexities that such persistence entails. Meshchaninova’s memoir-novel details the coming to terms with one’s history, but it also serves to remind people of their complicity, once again highlighting the power of the written word.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: