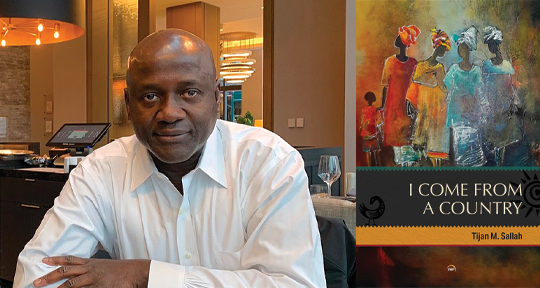

I Come from a Country by Tijan M. Sallah, Africa World Press, 2021

If The Gambia as a nation figures on the globe as “one of the world’s poorest and least-developed countries,” according to a recent article in The Guardian, there may be much cause for despair. As I leaf through the pages of Tijan M. Sallah’s latest poetry collection I Come from a Country, I can see a great deal of hope emanating from the vigorous pen of The Gambia’s leading poet, writer, and critic. The very first poem “I Come from a Country,” that gives the collection its title, shows how Sallah negotiates the dark terrains of poverty, unemployment, illiteracy, and urban squalor through images and pictures of what he considers essentially human. The opening lines of the poem, “I come from a country where the land is small, / But our hearts are big,” immediately suggest that it is the people who constitute a nation rather than geographical lines or boundaries. This is a land where “every one knows your name / . . . Where poverty gnaws at our heels, / But we have not given up hope / We continue to work.”

The collection’s recurring image of the sun signifies hope eternal. Hope, for Sallah, is not a “thing with feathers” as Emily Dickinson would have us imagine in her poem, “Hope is the thing with Feathers,” but it is a reassurance that “rises daily with the sun.” Life is difficult but with the resilience reminiscent of Hemingway’s Santiago, the common folks of The Gambia believe that “a man can be destroyed but not defeated”:

And if resilience were a person,

She will live in my country.

She will be a calloused-handed woman

In sun-drenched rice-fields,

With a child strapped on her back;

But with a love enormous as the sea.. . . Where we still believe in such things as

Sweating with your hand,

And still remember God and family.

And still support the indigent,

And carry Hope like oysters,

Sun-peeping from their shells.

Though based in the USA, Sallah’s intimate relationship with The Gambia remains deeply embedded in his sensibility. It is not restricted to a mere poetic expression of “imaginary homelands.” He seems to be carrying The Gambia within his heart and soul. If he is eager to show his love and esteem for the people of his homeland, he is no less vehement in offering his harsh indictment of tyrants like Yahya Jammeh who brought untold misery to the subjects for whom he was elected to be their custodian. Celebrating the overthrow that led to Jammeh’s exile, Sallah warns his fellow Gambians in “Jammeh-Exit”:

The detractors of freedom prey

On the unfulfilled pledges to the poor . . .

We must not be fooled;

That history does not repeat itself.

But, damn well, it does, if

Those who guard the doors of liberty

Sleep like dunderheads at sunrise.

Sallah is equally unsparing of leaders with dictatorial intent as is evident from the poem “Nasty Palaver of Donald Duck,” where his target is Donald Trump. Infuriated by Trump’s reference to natives of Africa as “people from the shit-hole continent,” Sallah castigates the “insolence from a drake, holding the scepter” for creating fissures in the most powerful democracy in the world with his hate-speeches against immigrants and people of colour. Sallah desires to see the earth rid of “such unbridled / Arrogance and greed” that cannot treat fellow human beings with respect and dignity.

This slender collection of thirty-two poems showcases amazing diversity and an encyclopaedic range of topics that cover people and events, cultures and civilizations, society and polity, calamities and pandemics. Poems like “Of India, I have hope for the Sun” evoke the poet’s ability to travel in his mind to distant lands as a cultural ambassador to share the message of freedom, peace, tolerance, and prosperity that comes from recognizing the otherness of the other with empathy and love. He imagines flying to India on the “chariot of his dreams” and, “sitting by the Ganges and the Brahmaputra,” desires to “watch pilgrims sail deep into their atman.” Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi’s ideals, he says:

That Mahatma, who taught the world

The enduring lesson of satyagraha.

Who knew that a spindle and a thread

Can defeat the depraved canons of Empire.

He visualizes Rabindranath Tagore sitting by “the date palms of Santiniketan” and “proliferating the wisdom among gurus/ About the enlightened path of Brahmo Samaj.” The India of Sallah’s dreams corresponds with Tagore’s vision of a “Heaven of Freedom”:

Of India, I have hope for the sun.

And of the rays of the sun,

Of the shadows of Dalits merging with the Brahmins

In mutual empathy and regard;

Of the silhouettes of Hindus, Muslims, and Christians

Melding love into an unrecognizable whole.

Of the rich breaking bread with the poor

To form a circle of incestuous kindness.

Of men and women, breaking the miseries

Wrought by fate, to shape a virtuous destiny.

Sallah seems to value the freedom of the individual as well as the collective. He derides the “Mending Wall” syndrome and asks in his poem, “Walls”: “How can a country grow that erects walls?” His rhetorical questions, in the same poem, “What would have happened to Relativity, / If Einstein was put in a cage? / What happens to caged children / When you set them free?” demonstrate his innate concern for issues that we normally turn away from. He castigates the gross materialism that has led humanity astray in the name of modernity. He is disturbed by the yawning gulf between the roaring rich and the utterly poor even in a land of plenty such as America. This is evident from his poem “Washington,” in which he avers “You have seen the world’s perfections and imperfections,” if you have seen the capital of the USA.

What makes this volume noteworthy is the intrinsic humanity of the poet, allowing him to offer exemplary tributes to the people he has loved, admired, adored, and revered. The epigraph by Stephen Spender—“I think continually of those who were truly great”—appended to the poem “Ballad for Mother” shows Sallah as a storehouse of affection blended with gratitude. He concludes the poem with the lines:

Among the many greats I know,

My mother was truly great.

If your mind racks with doubt,

I wish you had met my mother.

No less effusive are his remembrances of Dr. Lenrie Peters: “He loved the country like dolphins loved its river”; Chinua Achebe: “We will remember you for your dreams to make Africa fly”; and the Nobel Laureate for Literature Nadine Gordimer: “You loved truth like your birth.”

In these grim times, when the world continues to come to terms with the hazardous COVID-19 pandemic, Sallah writes in “Season of Vengeance”:

It is the season when death visited us

With a vengeance.

Corona crowned itself the king of the earth.

And we all prayed for the first time

For we were frightful.

We knew we had been careless

About things that really mattered.

The poem begins with the description of the traumatic fear that King Corona created by emerging as the great leveller that reduced to “a scandalous dungheap” all our “accumulated knowledge” of dealing with pandemics. As “Hospitals roiled with the drama of masks and ventilators” and “Mortuaries lay overwhelmed by / The rapid march of death’s spell,” Sallah points out how a complacent world was sent into a spin “by the scourge of the tiny” virus that wrought havoc on all fronts of human territory: social, economic, and political. Citing the warning given by Greta Thunberg, the young Swedish environmental activist, regarding the impending existential crisis from climate change, the poem laments how the world, lost in the funhouse of material greed and comfort, had to pay a heavy price:

We knew we had been careless

About things that really mattered.

Greta warned us, but, hey, did we listen

Earth is one; emissions must sink.

But the world blocked its ears,

And continued with business. Pests jumped,

And found free rein.

Arrogance, if not tempered, is poison for the world.

Sallah’s concern for the environment that we notice in “Season of Vengeance” is not an isolated instance. Many poems in the collection bring to the forefront his essential sensitivity in approaching events and issues as a caring poet. In “Slaying A Banjul Crocodile,” he shows his extreme displeasure when a group of children launch a brutal attack on the helpless crocodile. The crocodile’s attempt to defend itself makes the poet in Sallah remark: “one defenseless soul / Against a mob is / Sinking David against Goliath. / It instilled not fear in the mob. / It only spurred their excitement.” Likewise, a poem like “Moth” brings into bold relief the satisfaction and happiness that come to him from saving the life of the “blackish brown moth” trapped between the glass and wire gauze of a window: “I thought of leaving it alone. / But I noticed that sometimes / Leaving things alone may / End their fate.”

With a perfect rendering of emotions in multiple forms—ballad, haiku, and free verse—I Come from a Country is bound to command attention from both practitioners of poetry and lay readers. The easy conversational tone used by Sallah in his poems should remind one of Robert Frost who took pride in saying: “My poems talk.”

Dr. Nibir K. Ghosh, former Senior Fulbright Fellow 2003–4 at the University of Washington, Seattle, USA, is UGC Emeritus Professor of English at Agra College, Agra, India. He is Chief Editor of Re-Markings, an India-based international journal of English Letters in its twenty-first year of publication. He has authored or edited fifteen books that include Calculus of Power: Modern American Novel, Multicultural America: Conversations with Contemporary Authors, W. H. Auden: Therapeutic Fountain, Rabindranath Tagore: The Living Presence, Gandhi and His Soulforce Mission, and Beyond Boundaries: Reflections of Indian and U.S. Scholars, among others. His most recent work is Mirror from the Indus: Essays, Tributes and Memoirs.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: