In the first few pages of Paulo Scott’s striking Phenotypes, the protagonist and narrator describes the appearances of himself and his brother in contrasts: blond and brown, fair and dark. What follows is an immersive and urgent novel that addresses the ethics and injustices of Brazil’s colourism in Scott’s signature fluidity and perspicacity, exploring the limits of intentions and justices to probe at the centric forces of activism. As our first Book Club selection of 2022, it is a vital and incisive look at a nation—and a world—stricken with crises of race and identity.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

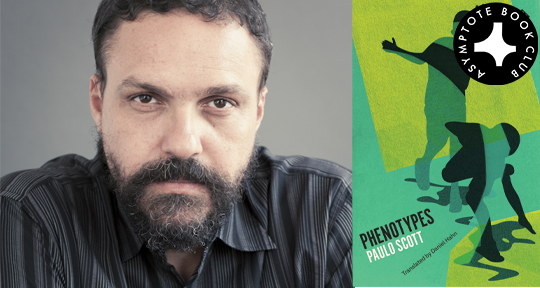

Phenotypes by Paulo Scott, translated from the Portuguese by Daniel Hahn, And Other Stories, 2022

What is the price of activism? Of wanting to change the world for the better? Do motivations, or true intentions, make a difference?

Federico, the protagonist of Paulo Scott’s engrossing and astute novel Phenotypes, is an activist by most definitions. He is co-founder of the Global Social Forum in his hometown—the “whirring blender” that is Porto Alegre; he has researched colourism in Brazil; he has advised NGOs in Latin America and beyond; and now, he is serving on a commission tasked with solving the problems caused by racial quota systems within universities.

Activism, from catalyst to consequence, forms an unavoidable part of his reality. The son of a white mother and a Black father, Federico has always been light-skinned while his brother Lourenço is much darker, and this ability to pass as white has afforded Federico privileges that his brother has never been able to enjoy. The discrepancy has been a lifelong source of awkwardness and discomfort, forcing him into a complex relationship with his own identity. Over time, Federico has ensconced himself in layer upon layer of guilt—a self-inflicted yoke around his neck that continually fuels his activism and shapes his life’s ambitions.

Federico’s impressive resume of achievements stem from his efforts to tackle Brazil’s seemingly insurmountable racism problem—but are these noble actions merely attempts at controlling his circumstances? Is he simply—as his former girlfriend Bárbara puts it—surrounding himself with “noise”? Bárbara, a psychologist who provides clinical care for those traumatised by activism, knows all too well the price people pay fighting for causes they believe in. In her patients, the constant struggle to topple a seemingly insurmountable system, as well as exposure to the true extents of injustice, has left them physically and emotionally drained. In certain cases, the trauma is irreparable.

But, of course, to speak of activism in a vacuum would be disingenuous. The true crux of the problem is what necessitates such movements in the first place: in this case, racism. The ever-shifting complexities of race relations in Brazil lie at the heart of Phenotypes—fuelling its narrative, motivating its characters, generating situations with unthinkable consequences. Indeed, such intricate questions are undoubtedly expected from a country as vast and varied as Brazil, where almost fifty percent of its inhabitants describe themselves as mixed-race. Throughout the story, the characters grapple with racial dynamics in a myriad of ways, with no easy solutions to be found.

There are as many ways to deal with racism as there are individuals, and we see this amongst the novel’s cast of characters. Federico’s father, a forensic pathologist in the police force, defies racism by ignoring its existence, staring his white superiors unflinchingly in the eye without speaking a single word about racial inequality. He treads the fine line of resistance that allows him to be where he is, but goes no further. Likewise, Federico’s mother discourages mentioning the problem at all, preferring to preserve her home as a peaceful sanctuary where such notions can be side-stepped and swept under the rug.

At seventeen, Federico, frustrated that his mother insists they are a Black family while keeping Black culture at arm’s length, challenges her thinking. Her response is telling:

The answer is that I worry about our family, About the health of my children, Of my husband, I worry about our having peaceful lives and so I don’t concern myself with militancy, I want a house where there’s peace, because it’s peace your father and your brother need, From the front door in, On our little patch of land, inside our house, is our place, Our ground, Our sacred space, Our space for being happy, for strengthening ourselves for life, and she sighs, Your father’s in the police, You know all the risks he takes, You know the price he pays for not having to lower his eyes in front of his superiors, who are all white, yes, You know the price he pays for being honest, decent, too much sometimes [. . .] We do see the racism, We know what racism is, but we don’t give in[.]

Despite this upbringing, seeing but doing nothing is not enough for Federico; he must take action, even if only to assuage his feelings of shame and atone for his undeserved privilege. Still, he does so cautiously—within the framework of existing structures. He researches, sits on commissions, and advises multinationals. He doesn’t take to the streets.

By contrast, Federico’s combative niece Roberta epitomises the younger generation, angry and mutinous in a way that strikes fear in her uncle’s heart; he cannot help but feel that her unbridled rage will ultimately endanger her own future. Indeed, when she is arrested for possession of a former police service weapon and threatened with terrorism charges, Federico sees in her eyes a wild defiance and—more perilous still—an animal fear that chills him to the bone. Unlike her uncle, Roberta seems driven by a primal desire for revenge that risks muddying her purpose, causing her to act emotionally rather than pragmatically. But it is hardly surprising that a young girl who has witnessed injustice and police brutality would be compelled to resist and rebel, or even resort to violence; the fear and anger are the consequence, not the cause, of her militantism.

Phenotypes offers few answers—and expecting them from a single work of fiction would be futile. Instead, Scott opens the floodgates to a myriad of questions, probing the uncomfortable topics that his fictional (but all too real) bureaucrats would rather leave undisturbed. Posed as the novel’s eyes and ears, Federico is the lens through which we view these issues, and the means by which we understand the racially charged situation in Brazil—described as “the sleepwalking country.” It is Federico’s disbelief we feel upon hearing proposals to implement racial identification software, Federico’s squirming discomfort as he remembers instances wherein he passed as white to the detriment of others, and Federico’s vague malaise at the thought that he has long spent his youth and lost too much along the way. It is this personal angle that brings the novel’s broad, sweeping themes into sharp focus.

But the novel’s most striking feature—one that jumps out from the first page—is Scott’s sprawling and idiosyncratic writing style. He favours long sentences (in fact, the novel’s second sentence spans twenty-one lines and is incredibly broad in scope), but the writing is taut and polished, never rambling. In an essay published with Asymptote in 2014, translator Daniel Hahn describes the process of rendering Scott’s previous novel, Nowhere People, into English, and refers to the author’s style as “uncompromising”—yet still concedes that its singular quality made it all the more enjoyable to translate. There is a certain lilting cadence to the writing that belies its serious subject matter, but the voice surges forward with a dogged, unrelenting rhythm, reflecting the never-ending cycle of the racial tensions it depicts. The syntax is painstakingly constructed, and Hahn’s essay, as well as the fascinating translator’s note at the end of Phenotypes, goes into detail on the meticulous thought processes that allowed his translation to take shape.

This is a novel, then, which poses both thematic and linguistic challenges, engaging the reader equally on political and aesthetic levels. In raising the issue of racism and one’s actions in the face of it, the book itself is arguably a force of social progress and understanding, laying bare the true nature of a country which, according to Scott, is too often erroneously seen as a beacon of “ethnic harmony.” Phenotypes is innovative, deftly precise in its form, and utterly profound in its content. Scott’s work in bringing contemporary urgencies into fiction is uncomfortable and often unsettling, but necessary—and, ultimately, unforgettable.

Rachel Farmer is a translator, interpreter, and subtitler based in Bristol, UK. Her literary translations have appeared in SAND journal, No Man’s Land, and an anthology from Two Lines Press. Her latest translation is forthcoming from Strangers Press. In addition, she acts as chief executive assistant for Asymptote Journal and writes book reviews for Lunate magazine.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: