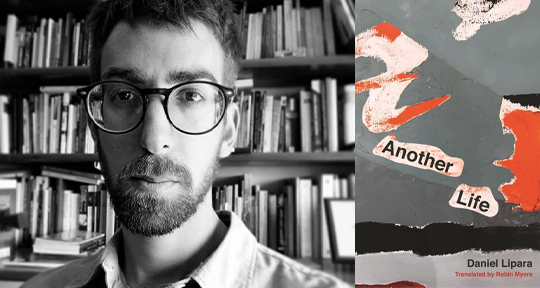

Another Life by Daniel Lipara, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Eulialia Books, 2021

The first poem in Daniel Lipara’s debut collection Otra vida, released in English as Another Life (Eulalia Books, 2021), is a page and a half long. Entitled “Susana, lotus flower,” it lasts a lifetime. Many lifetimes. The poem is sweet and painful, excruciating and grotesque, charged with fragility and hope and tenderness and memory (“her father the son of a butcher who fled the pogroms all the way to Argentina”), visceral with pain (“they shrank her stomach with a belt the belt snapped open scratched her innards”), and void of commas. It’s as vivid as it is memorable, and it sets the tone for the rest of the book.

Another Life is a family album laced with beautiful writing; I like to think of the poems as spotless, multichapter vignettes, quickly spun by a well-oiled stereoscope. In Lipara’s ranging collection, we follow a family—a very real and flawed family—moved and motivated by love, grief, and hope, as told to us by a narrator in awe with his surroundings.

After pious aunt Susana of the opening poem, we read about Jorge—the father, “the tiller (. . .) and master griller,” and later Aeolus, the god of the wind. As personal and intimate as Lipara’s work feels, the narrator also becomes preoccupied with what plays out in the greater background, with its history, characters, tales, and myths. In this, Another Life feels both quotidian and epic. Soon after, we meet Liliana, the mother, who is “five foot nine she has big bones and bleach blond hair” and is dying of cancer, though we don’t learn about this until later. (It is hinted at subtly, however, during her first appearance: “(she) lays her hands onto my mother’s vengeful cells.”)

After this introduction, we meet Sai Baba of India; Liliana will travel to his ashram looking to cure her cancer. This journey is first introduced as a premonition: “I dreamed we went to India and your mother was healed,” says Susana. Then we see the family waiting at the airport, on the plane, and reaching Indira Gandhi Airport. We see water buffalos. We see rice fields. We see India through the eyes of a young Daniel, and we see him experiencing the country, silently amazed by its colors, odors, sights, and sounds—again being drawn into the background with its world of fascination, again merging the quotidian and the epic.

Daniel’s fast-paced narration and the book’s story-driven nature are made all the more memorable when we come across disarmingly beautiful descriptions: “the island (. . .) is a desert of obsidian adrift in wine-dark seas”; “the soundless cobra with cosmos printed on its neck”; “earth strewn with stones as if a mountainside had shattered”; and my favorite: “like the spider turning its prey around and around engulfing it in thread that’s how the tailor wraps my mother in a sari.” Lipara’s lucid imagery and lyrical beauty—masterfully translated and reproduced by experienced translator Robin Myers—makes Another Life a memorable and scenic read.

Yet beauty, in Lipara’s book as in real life, is often placed alongside grotesque images, rancor, sorrow, and even silliness. So while we see a glimpse of Jorge’s fears and insecurities (“what if something happens to you (. . .) I’d crash the taxi turn to dust let the wind blow me away and let my bones drift down to earth”), we also see Susana’s silly and absurd—yet loving and genuine—take on religion and permanence (“Every tree has a soul and so do cars and furniture”). Silliness and absurdity, however, are not used as comic relief. In Lipara’s world, beauty, meditation, and ridiculousness are not mutually exclusive. Together with the author’s stunning writing, they form an authentic portrait, an epic and authentic take on a family, a place, a time, and a mother clinging to life.

Daniel’s narrative style and interest in mythology, as seen in Another Life, is perhaps a direct influence of the books and authors that he has translated from English into Spanish: Alice Oswald, Anne Carson, and John Burnside—three T. S. Eliot Prize-winning authors. From Alice Oswald, Daniel translated Memorial, built on Homer’s Iliad. From Anne Carson, he translated The Beauty of the Husband, a tragic tale of a marriage (it’s important to mention that Carson has been famously influenced by classical Greek literature as well). Finally, Daniel translated John Burnside’s Learning to Sleep, where we also see the poet’s mother as a ghost; Hypnos, the Greek god of sleep, also makes an appearance, and is as infused with discomfort and agitation as Another Life’s grimmer poems—”all day my voice hid in my throat like a mouse in a dresser.”

Upon reading Daniel Lipara’s original Otra vida —cleverly included at the end of Another Life— I can’t help but also praise and applaud Robin Myers’ translation. She was able to masterfully and imaginatively capture Daniel’s stellar writing and impactful images—not an easy feat, considering his elaborate yet crisp descriptions (“he taught me how to build a fire with branches eucalyptus leaves bark shavings the air snaps we burn the meat fling entrails to the flames of leafless logs”).

Lipara’s subtle humor also remains intact, as well as his casual yet remarkable poetry. John Burnside wrote that Robin had “inventively and scrupulously” translated Otra vida. Speaking on the collection, author Conor Bracken wrote: “The poem that Robin Myers has brought us does what great poems do: show us the ancient in the contemporary.” One must also note how Robin let Spanish roam free in her version; Ciudad Oculta is not Hidden City, Monte Pelato is not Pelato Mountain. All accented proper nouns keep their accent, their tilde: Héctor, Aragón, Analía, González, Catán. Except in the rare case where Robin changed the name of Jorge’s dog from Prometeo to Prometheus, Another Life feels free of unnatural approximations and anglicisms; her translation is not invasive, but permissive and authentic. Robin’s translation skillfully captured Daniel’s lyrical beauty, grace, wit, and depth with care and consideration.

Daniel Lipara’s Another Life is a tiny cosmos, a subtle and refined explosion, a bursting ocean with waves crashing on a nearby and familial shore, a firm embrace, a warm laughter; much like Burnside wrote, this is a “gem of a collection.”

José García Escobar is a journalist, fiction writer, translator, and former Fulbright scholar from Guatemala. He got his MFA in creative writing from The New School. His writing has appeared in The Evergreen Review, Guernica, The Washington Post, and The Guardian. He’s a two-time Dart Center fellow. He writes in English and Spanish. He is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for the Central American region.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: