What’s more pressing than a natural disaster? An opium addiction. The titular “emergency” in Mahsa Mohebali’s award-winning novel refers simultaneously to shuddering Tehran and the pressing urge of its protagonist, Shadi. In vernacular as electric as it is poetic, In Case of Emergency paints a mad portrait of Iran and its electrifying counterculture, as we follow the brilliantly acerbic Shadi on dissolving boundaries of need and want, of gender, of revolution. The Asymptote Book Club is proud to select this defining text as our last selection of 2021.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

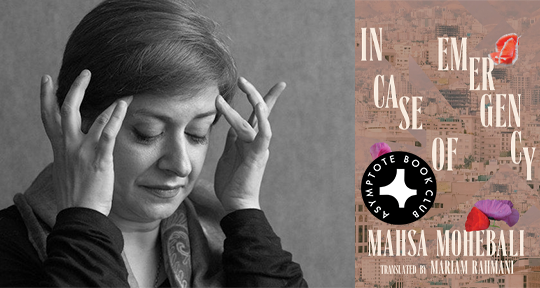

In Case of Emergency by Mahsa Mohebali, translated from the Farsi by Mariam Rahmani, The Feminist Press, 2021

Shadi wakes up to a brutal comedown in her family’s Tehran home. The earth’s been “dancing Bandari”—shimmying, stamping, and shaking, all night, which she actually wouldn’t have minded so much if it weren’t for her mother’s screaming “ten times for each tremor: How many screams does that make?” After a night of earthquakes that show no sign of stopping, her family is preparing for an exodus, but Shadi only has two opium balls left, and that won’t do in the middle of a crisis—or any other day. So she, the well-off daughter of a philandering university professor and a revolutionary-turned-housewife who absentmindedly clicks digital prayer beads, dons masculine clothing, setting off through the upended streets of Tehran to find her next fix.

Shadi, like many of her peers who grew up in post-revolutionary Iran—the majority of the population—is well-educated, jobless, and disillusioned with the repressive regime that hasn’t delivered on its promises. Mahsa Mohebali’s In Case of Emergency (“Don’t Worry” is closer to the Farsi title) was released just one year before the thirtieth anniversary of the Iranian Revolution, and its fictional earthquake, as well as the ensuing chaos and the repeated refrain of the city’s hardened youth—“Everybody relax. This city is ours”—was said to have foreshadowed the real-life Green Movement protests soon to come. Shadi herself, however, is a far cry from either the revolutionaries of her mother’s generation or the protestors of her own: “Arash’s dumb-ass logic is spreading like a breed of Barbapapa,” she laments. “Was the earth fractured or just these idiots’ skulls? This city is ours—I’d really like to know what that actually means.”

Though her profile—including the opium addiction—matches many of her country’s youth, it isn’t often represented in Irani literature. This is due, on one hand, to political censorship. The original version of the novel made it to press with only limited edits, and won the prestigious Houshang Golshiri Award—before being banned on and off. Mohebali is also, as of this writing, prohibited from public speaking. However, social censorship is also at play; Shadi speaks the crass, cosmopolitan slang of the streets, not the lyrical Farsi of the page. Globally, in all four cardinal directions, the expansion of a literary establishment to include vernacular languages and subculture has been characterized by both resistance and fascination; this would be one such catalytic work.

Though Shadi’s countercultural transgressions aren’t quite as shocking in the Anglophone world, she breaks ground in other ways. Translator Mariam Rahmani observes in an essay that: “In the Orientalist imaginary, Iran is stuck in the past; the contemporary publishing industry is often guilty of producing this same fantasy.” In Case of Emergency doesn’t ignore or explicitly reject Orientalist stereotypes of women, but it does tease them. Rahmani herself points to a gorgeous scene between Shadi and her oldest friend, Sara—the wealthy great-granddaughter of a former Shah’s favorite concubine—which is laced with homoeroticism, bravado, hedonism, and above all, tenderness. “This particular Orientalist fantasy,” Rahmani notes, “comes with the finger.”

But Shadi’s expedient crossdressing and Sara’s hospitality aren’t the only versions of femininity on offer. Some women are avian: sparrows when vulnerable and simply birds when riled. Female revolutionaries abandon their families to shout for hopeless causes. The dancing earth itself feminized:

The earth shudders and the shudders ripple through my body. They start at my fingertips and run through my shoulders and groin and damn! Let the Bandari begin. Mother Earth must be down there shimmying her big meaty breasts. The tremors speak to me. Speak to me. Speak to me. I feel like it’s my first time ever lying on the grass. I suckle at its scent. The earth settles down, a pause in a long sentence. I close my eyes, walk my fingers through the grass. Smells like rain. The smell of wetness, the smell of trees. I wish I could sink, pour into the earth and dance with her. Let the tremors crawl through my body. I don’t want them to stop. I want to lie right here on this grass forever sucking on its wetness. I want my breasts to shiver with her shivers and make waves.

Shadi is so much more than a political symbol with a foul mouth. She’s a young woman stuck between the part of her that cares and the part of her that’s terrified of the consequences of caring. When she makes a run for it in the morning, leaving her distraught mother in the care of her responsible older brother, she’s out to find drugs, definitely, but she’s also out to check on her disturbed friends and find her missing grandmother. Her two missions are sometimes aligned and sometimes in conflict, and that central tension is what makes her such a compelling character.

Shadi’s left with big questions—life and death questions—about many of her loved ones, having very little to do, actually, with the physical earthquake itself—which jingles chandeliers more than it fells buildings. Ashkan, a child of her mother’s comrade from back in the day, is suicidal. He sends her an alarming text message first thing in the morning, causing a fog of thoughts and emotions to envelop Shadi, lingering through the rest of the day. She doesn’t want him to die but can’t convince even herself why he shouldn’t. She doesn’t want to go; it’s not her turn; what’s the best way to talk him down? Did he take pills or opium? Is the opium salvageable? She puts her playlist on shuffle, or “leave-it-to-fate,” and fate offers her pretty clear signs. “I’m sure it’s Ashkan’s spirit calling out to me. I must be the most cowardly little bitch the world’s ever seen. But I don’t want to go, I want to stay here and watch the crowds. Ashkan, you asshole. Isn’t it a shame to kill yourself on a day as perfect as this?” But eventually, she goes, and the macabre visit is fortunately balanced out by the comedic presence of faithful Crassus, Ashkan’s lighter-fetching dog, presumably named after the wealthy Roman politician.

Later, Shadi finds her grandmother, who lives with Alzheimer’s, in the middle of a riot. She acts as if in a dream, as if propelled and then paralyzed by a larger force:

Camo fatigues. Borrowed big boots. She shouts. Kicks and screams at the cops crowded around her. What are you doing here? And what are you wearing? And why is your hair dragging on the ground? Please stop kicking them . . . She shouts then disappears into the background, into a sea of black cars.

“Nana Molouk?”

I start pushing through the Green Suits elbows out. A wall of chests blocks my way.

That’s my grandmother! I stand on my tiptoes. Where are you taking her?

“That’s my grandmother . . .”

My shouts fade away. Her shouts fade away . . . She runs toward me. She’s escaped! A blow to the back of the knees and she folds. Her long white hair drags on the ground.

Shadi’s worried about her grandmother, as she’s worried about Ashkan. She can’t bear the thought of her grandmother in police custody, but neither can she bear the thought of tracking her down through the city’s notorious prisons—a challenging enough dilemma even without considering a looming withdrawal. Indecision eats away at her.

As a reader from the United States, I’m curious about narratives from Iran that contradict those, few and simple, offered by the mainstream media. However, it would be a mistake to reduce Shadi to a vehicle for representation—and a slight to the two brilliant artists who gave her voice. She’s a beautiful character, brimming with conflict, and capable of reproducing that conflict in the reader, inspiring repulsion and sympathy in turns. Rahmani does a wonderful job of depicting femininity in general, and Shadi in particular as shifting and diverse. Lyricism comes to her as naturally as profanity, and her vulnerability is just as convincing as her callousness. Between the insulting pet names and the international inflections, In Case of Emergency displays a gift for description and a masterful knack for challenging the expectations of structure. The result is artful chaos, as brilliantly orchestrated and lovingly keyed as the Bach movements Sara rehearses on her out-of-tune piano.

Lindsay Semel is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: