In the multimedia exhibit, “i write (in Vietnamese),” held in Hanoi during March of 2021, a group of poets and artists grappled with the fraught nature of writing in Vietnamese through a series of multifaceted installations crossing between poetry, photography, and other forms of visual art. In this essay, the Vietnamese writer Phuong Anh reflects on the exhibit through conversations with the artists and their works to discover their relationship to the Vietnamese language, their experiences of living in multiple languages, and the significance of translation for both the artists and herself.

What does it mean to reside in a language?

What does it mean to write in a language?

These two questions dance around in my mind, as I pen down letters with diacritics, forming monosyllabic words, known to me as “Vietnamese.” Although every now and again, words from other places are inserted. They mingle together and ring in my ear like soft lullabies. Yet, when it comes to defining what language they are, what literature they are, no labels have yet to satisfy me.

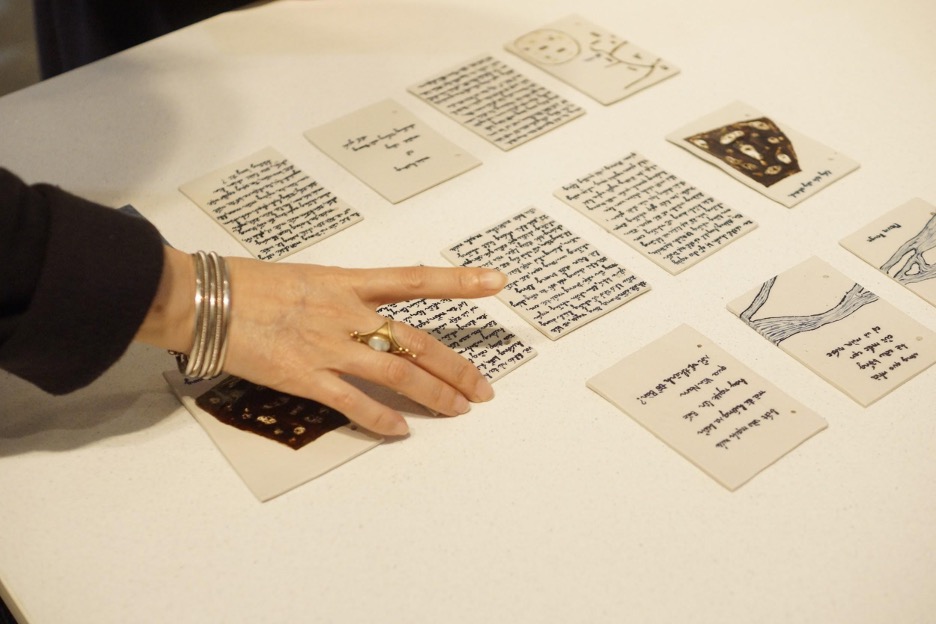

“The unsendables,” Hương Trà & Kai, photograph by Bông Nguyễn

Such a dilemma is encapsulated in the title of the exhibition i write (in Vietnamese) that ran in March of 2021, right after the lift of Hanoi’s third lockdown. It took residence at first in the Goethe Institute before migrating to the Bluebird’s Nest Cafe. It was composed of a multimedia showroom, displaying the multifaceted nature of writing “in Vietnamese.” A label so constrained by past and current cultural politics, yet so liberating—a mini tug of war, echoed by the brackets, which both confine and protect the language.

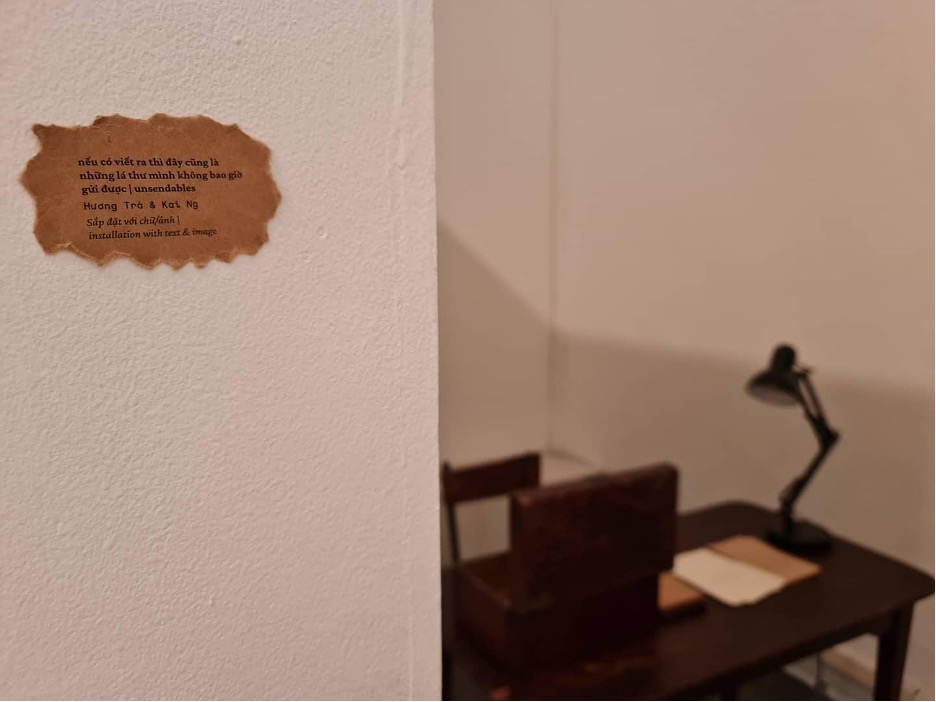

The exhibition brings the creator and viewer closer to the process of art-making. For example, in Hương Trà and Kai’s project nếu có viết ra thì đây cũng là những lá thư mình không bao giờ gửi được | unsendables, viewers were invited to come, sit down, and write. In that room, there was a table on which there were two stacks of paper: one labelled “here are the letters that depart” and the other, “here are the letters that stay.” Those who chose the first stack could have their letters sent; while the writing of those who chose the latter “will never be able to be sent” and would remain forever with the exhibition. This project also connects languages not just through the bridge of translation but also by placing them within the same space: English and Vietnamese on one double-sided paper (chiếu| |uềihc reflect| |tcelfer), on a single page (where is my heart?; Journals to), or on the same line (slow dance in a burning room; skin.da).

một điệu nhảy trong căn phòng bốc cháy

are we slow-dancing?

i touch you with all my grief

my sorrow my heart

my mind

oh this moment i need you to cry

cho những lần ta không hôn một ai . . .(slow dance in a burning room by Hương Trà)

The choice of placing English and Vietnamese so close to one another in a poem that expresses so much vulnerability was what stood out for me the most in this poem. The speaker’s voice sounds almost like a plea, for another person, or perhaps us, to simply listen. In the middle of the poem, the rhyming couplet between English and Vietnamese words, “cry/ một ai,” subtly marks an acceleration of emotion. Here, the meaning of “một ai,” which in this context means “nobody,” through its phonic union with the verb “cry,” conveys a certain fragility in the speaker’s voice. The feeling this creates for me is like when the rollercoaster has reached the top and is about to plummet down, that moment of serenity before the adrenaline rushes in. The poet also told me that she actually wrote this in one go, reflecting the organic structure of this poem. Allowing these two languages to mingle in the same space reveals a new possible way to write in “Vietnamese.”

As editor Nhã Thuyên wrote in the introduction to the online version of the exhibition, “tôi viết (tiếng Việt) | i write (in Vietnamese) is by itself a hesitation, a dilemma, going back and forth.” It was this question that shaped my conversation with some of the lovely artists whom I was able to interview. Most of their immediate responses were “since I see myself as Vietnamese, whatever I write I’d say it is Vietnamese.” However, some did acknowledge feeling tentative with that label, especially those who are bilingual and created work in both languages. But I feel that this exhibition, despite the tentative brackets, is an unabashed exploration of the different Vietnamese poetic voices, validating each and one of them, no matter their form.

For those working in two languages, Vietnamese was a language of intimacy, while English was the language that liberated them to explore ideas. This is partly due to the way literature is taught in Vietnam: didactic and constrained. Indeed, for some, it was through English that they first became conscious of their “writing,” which then allowed them to ambitiously create art in Vietnamese. Often through a kind of translation, these artists take poetic concepts learnt in English and bring them back into the Vietnamese language. For instance, bilingual poet Thu Uyên first created poems in English before migrating back into the Vietnamese language. In the process, she brings remnants of that so-called “anglophone voice” with her, which can be seen in the prose poetry that is used in many of her poems, or certain sentence structures like in her //black/white/ poem: “bây giờ. tớ. cảm giác. mọi thứ. thật như cách nó không cần là.” This phrasing closely follows her English version: “now. I. feel like. everything. is as real as it doesn’t have to be.” This could signal that the Vietnamese version is the translated version; and some might say it sounds “unnatural” or “not native-like,” but for a bilingual like me (and I think many others in Vietnam and its diaspora), it is as natural as it could be. Moreover, by having the poem shown in a “Vietnamese” exhibition, there is a sense of that “foreignness” being neutralised: the poet reclaims her rights to reside in her mother tongue.

This process reminds me of Mireille Gansel’s memoir Translation as Transhumance, in which she compares the act of translation to a shepherd bringing a flock of sheep across land to find more fertile ground. It is also reminiscent of the Vietnamese nineteenth-century New Poetry movement, during which, partly through translations commissioned by the French, Vietnamese poets were exposed to a new heuristic view of poetry. The act of translation also becomes necessary because for some, English remains foreign, almost alienating. Translation thus possesses the potential to provide them a reliable path back to their language of residence.

“A Broken (Note)book.” Linh San

A recurring motif in the exhibition is reflection. Often, where there is a translation, it is placed in a way that looks as if it is reflecting the Vietnamese version. However, this does not mean that the languages are one and the same. Instead, it is more like looking at oneself through different reflective surfaces. Some are clearer, some are blurrier, some are sharper. But all these reflections come together to reveal one “self” in a continuous feedback loop, something similar to Lacan’s mirror metaphor in his “Mirror Stage” theory. Even the theory’s idea of the “self” being formed through the “Other” can be linked to translation, in the sense that a language becomes itself through similarities and importantly, through differences. Translation can thus be seen as a method of introspection. When asked how they felt about having two versions, those who wrote in one language like Lan Anh said that they helped her to gain a new perspective on her Vietnamese version. Similarly, Linh San said that in the case of the particular poem Houston’s beach, the contact with English led her “to sharpen the words in Vietnamese, making it more stern and clearer.” However, this is not always the case for her. While those who self-translate see translation as a medium for recording their inner monologue, and perhaps dialogue.

The exhibition breathes new life into the usual inked graphs of poetry, dressing them in silk threads on embroidery frames like Morsel-well, or overlaying photographic filters in the chiếu| |uềihc reflect| |tcelfer series, or freezing the “ink” on ceramics as in A Broken (Note)book. These methods let the words take up a three-dimensional space, exploring the “thinking of a word, a letter as an object or a living thing,” as Nhã Thuyên declared in the introduction. For instance, layer is added to Thuỳ Dương’s Morsel-well, as letters are embroidered in a circular motion on a circular frame, echoing sounds in the poem. It presents an exquisite exhibition of Vietnamese prosody, exploring in-depth the potential musicality of each Vietnamese phoneme. The English translation keeps that focus:

I lie assembling rhymes regretting the nonsense squinting writ large on

The phone’s sheet-like figure

Qel,rel,phel,sel,del,hel,

Xel,nel,thel,nhel,khel,chel,trel . . .(Morsel-well, translated by Nguyễn Lâm Thảo Thi)

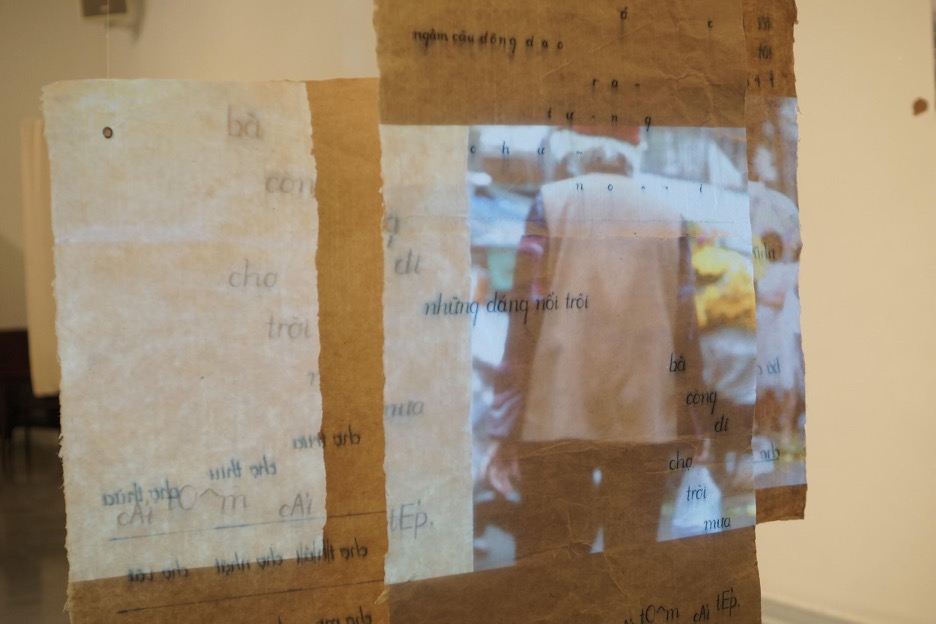

During my interviews, we talked about the series chiếu| |uềihc reflect| |tcelfer written by Thu Uyên, whose poems are each accompanied by a photograph taken by Kai. We talked about one in particular that stood out to me: Yellow. The poem explores the idea of touching. Something so intimate and innate in a sense, yet so hard to grasp, especially in a culture that is still reluctant towards public displays of intimacy. However, this exhibition does the exact opposite: it renders intimacy accessible and embraces closeness. Kai’s accompanying photograph in the series further highlights the sense of intimacy, as each shot is a close-up of a person’s exposed skin.

. . . in the stomach is also what most easily injures. when I was small my mother wasn’t

home a lot, I stayed with my aunts or bà ngoại and just clung to that strip of skin below

the elbow to fall asleep. I’m a child who clings to cycles and patterns. the theory of

touch precedes grip, cling, pull, tug, haul. I learn touch for so long and don’t touch any-

body. she said touch doesn’t need to be learned, only done, maybe what I could not . . .(Yellow, self-translated by Thu Uyên)

In my initial reading, I felt a dynamic contrast between the theme of vulnerable intimacy explored in the poem and the colour yellow, which I often associate with something positive and warm. However, when discussing this point with Thu Uyên, she revealed to me that she actually thinks of yellow as an oppressive colour, easy to stain and easy to drown out, a sentiment which her collaborator Kai shares.

“chiếu| |uềihc reflect| |tcelfer,” Thu Uyên & Kai

Intrigued by this relationship between the visual and textual literature, I asked the artists what colour comes to their minds when thinking about Vietnamese literature. For poet Thu Uyên, it is a light brown. Brown for earth and roots, and light because the roots haven’t been able to dig deep into the soil. However, Kai didn’t name a colour but only described that the hue is light. For poet Hương Trà, it is the colour grey because its existence is often contested. The colour “xanh” was also mentioned in conjunction, a colour which could mean anything between the pigments blue and green. Despite the artists claiming it would be going a bit too far to call Vietnamese literature “xanh,” personally, I feel that it is. As someone who was educated in a French system then in an English one, I have always lived at a distance from Vietnamese literature. The gap seems to have widened over the past two years, as I was unable to go back to Vietnam. Therefore, xanh’s connotations of “small” and “under-developed” ring true to me. From here in the UK, across the sea, the Vietnamese literary voice is still faint to my ear. It still conjures up an unsaturated hue for me. I often end up feeling confused.

This sense of disorientation is echoed in Linh San’s poem where is my house. The poem evokes the feeling of floating in the middle of the ocean, with no stabilising anchor. One simply drifts and without knowing, has gone far away, haunted by the amnesia of one’s origin. Yet, as a reader, the words and their evoked images construct something close to a pathway, leading them, not home, but close enough, even through the English translation.

few tangled lines, get down from the hammock, the dawn is not yet gleaming, I come out of

the garden full of strange flowers, toward the sea, i meet two boys talking in a language i

don’t know, how far did i go, when did i start my journey, and where are you, i myself can’t

recall the traces.(where is my house?, translated by Châu Hoàng)

However, Linh pointed out that the poem was difficult to translate because so many of its images are more meaningful in Vietnamese. For instance, the image of “betel vines” has a lot of cultural significance in Vietnam, and Linh San said that it took them a long time to settle on this translation as the poet was scared certain feelings wouldn’t be communicated. Indeed, I think that for Vietnamese people the significance of “trầu,” as understood within the Vietnamese culture, has more force in its Vietnamese form than the English “betel.” Lan Anh’s âm nước | letters of water may also suffer from its emotions becoming “lost in translation,” as the poem centers around a character whose iconic status is more accessible in Vietnamese.

“âm nước | letters of water,” lananh & Bông Nguyễn

The idea of words as a pathway is evoked by Thuỳ Dương, author of Morsel-well, who said that it was through the act of consciously writing, reading, and creating art, that she was able to become more aware of living in this language. Through writing, the language is then transformed into pathways, leading her to “new spaces in the imagination, of other ways of experiencing, of other ways of thinking.”

As someone who lives in several languages, this exhibition gave me hope of growing to feel more comfortable with the label of “Vietnamese” through the expansion of its meaning. Now, the hue is more opaque. Now, the voice echoes louder. As Thu Uyên expressed, the label only acts to give the other person a point of reference, but what it truly means can be left indefinite because for her giving up one of her languages outside of Vietnamese would be like giving up a part of herself.

But there is still so much more to this exhibition. Some works I did not get the chance to mention: for example, the films and experimental poems by Red. Many of the works have also been reworked and furthered by the artists. Therefore, this is only a snippet of what the space has to offer.

So what does it mean to reside in the language? This exhibition and my interviews with the artists suggest that to reside in a language is to be conscious of it. It is not just about sounding “natural” or “like a native.” It is to recognise its presence, to taste its sound, to feel its touch. Listen to its rhythm, and let the sound make you feel things beyond day-to-day life. Such residence is also unstable, and therefore you cannot stay still but you have to continually remodel the roof. Perhaps, this is what it means to write in a language. But sometimes you need to get new materials. At that time, you go over the bridge of translation to find them. Of course, you won’t be able to find the exact materials you once had, but something still adequate, on which you would perform touch-ups, and the overall shape might just change ever so slightly.

Phuong Anh is a BA language and culture student at University College London, where she is studying Italian and Japanese alongside cultural studies.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: