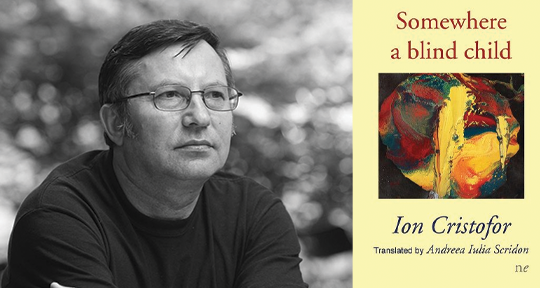

Somewhere a Blind Child by Ion Cristofor, translated from the Romanian by Andreea Iulia Scridon, Naked Eye Publishing, 2021

Oh, what a sinister story, what bothersome spectres

my bedstead is creaking.

We will have to move in the night

to other rooms to other countries to other life-stories.

Spirituality, references to the Scriptures, and direct calls from God—Romanian poet Ion Cristofor is known as a “modern Christian poet,” but Somewhere a Blind Child exemplifies his idiosyncratic approach to faith. Drawn from nearly forty years of work, these selected poems are translated into English for the first time by Andreea Iulia Scridon, a translator and poet herself. They are spiritual, but also ridden by spirits; they frequently allude to the scriptures with reverence, but also do not refrain from ridiculing them at leisure—God calls in, but he himself “gets no erotic phonecalls.” Cristofor’s numbingly clear awareness around the contradictions of the modern world—in realms of religion, history, science, and death—keeps the reader from being lulled into any false sense of comfort, whether by confidence in faith’s power or excessive hope in reason. When earthly pleasures do barge in, however, their offer to distract from pain and worry is accepted with abandonment and sensual relish, no matter how ephemeral their soothing effect.

When she undresses on the couch

the blossom-laden trees all move into my bedroom

their love-sick leaves becoming delirious.

It’s autumn, Lord, it’s so late in heaven

and love is a blue orange in your hand

In this unusual meeting place between the chilly high planes of the spirit and the dirty warm ground of the senses, visions flourish. It feels oddly logical; wracked with doubt, a mind can become overattentive to extemporary signs—the shape of a cloud or the temperature in a room, taking them for premonitions or glimpses of the truth that lies behind the real, as they appear and disappear in the surreal and overheated atmosphere. The senses, if capable of guiding reason, can also distort it, making room for the incredible, the strange, and the eerie.

a white phantom passes through the rooms

reminding you of an hour of love

that once passed over you like a galloping herd of horses,

like a reckless ocean wave.

And now flocks of starlings proclaim you governor of the

province

and towards evening the clouds send you dark ambassadors.

The world is permeated by significance—but who put it there? Cristofor does not seem to infer that It is the kind of meaning simply bestowed from above; rather, it is a tormented knowledge resulting from long intimate conflicts—awe, fear, and reason battling together and kicking up a dreamy mist. It is by virtue of this knowledge that the relationship between the poet and God is not one of submission or exalted worship; one moment the poet marvels at the generosity of God in the vastness of creation, and the next he resents God for his distracted, imposing ever-presence—for the way in which he takes away life and the pettiest of pleasures with equal absent-mindedness.

the cloud was a brother to me the whole afternoon

then God beat it to who knows where

Here, Scridon chooses the verb to beat; God is powerful and therefore he can be violent, but he can also beat clouds like cream, making something light, beautiful, and pure. In the face of this awesome potency, the poet both marvels at God and rages at his indifference in the face of injustice, cruelty, and pain. Thus the poet exacts a small but interesting revenge—to make fun of God, the angels, creation, the sacred, and the holy. God’s most spectacular acts are deflated by the poet’s irony and wit, which clear the air to show an ambiguous divinity, at times as cruel as the humans who are supposed to be his inferior:

from my window in the evening I look out at the solemn faces of

idiocy

brutality satisfies its every whim in its impeccable tuxedo

scoundrels grin in the limousine their consciences are up for

bidding

now the beast brings its victim roses

while you Lord have screwed the moon in like a lightbulb

you’ve swept the stars up and let the birds of prey out

our roads go mysterious ways like those of the night butterfly.

Still, in attendance is always one undisputed queen: Death. Death appears constantly, often taking the place of God as the regulating principle and the structure beneath life. Their roles and identities contrast, overlap, and exchange fluidly while the poet reflects that he “can accept that the only universal language is death’s silence.” A language made of silence—with this oxymoron Cristofor both spells out the absurdity of life and death as realms that cannot exist without their opposite, and forges their connection. Death is not only the backdrop of life: it is both the absence of life and its trigger. Cristofor’s visionary images stand against the void while being triggered by it, for the poet is able to understand silence as a form of communication, with its own grammar and purposes. Death can, with one hand, mute the hubbub of life through one single image, a realisation of the fragility of existence; with the other, it prods the living to live, coaxing them with words at times “dirty” and at others persuasively sweet.

death will plough furrows

cursing defiant bulls with dirty words

lashing a whip at the swords

coaxing ploughshares along with honeyed words

This is, then, where Death, the divine, and earthly pleasures meet—in the poet’s ability to sense a language in which dying, eternity, purity, and sensuality are not so much in contradiction as in relation to one another. It is, perhaps, not a coincidence that Death—though often just an elemental, non-gendered force—appears occasionally invested by a certain feminine and sexual aura. Sickles, women, and the colour black form a triangle that is carried through several of the poems in this collection. The notion of the “feminine” is also, unfortunately, where some considerably less interesting ideas emerge. Apparently feminine attributes, sometimes graphically described, are scattered about—perhaps in an attempt to achieve a boldness that matches the heightened register of the poems. This, however, comes across as forced, and certain casual comments on the ideal relationship contain stereotyped and reactionary views on women—though that doesn’t mean that the poet describes the love for these women vulgarly; love and sex are mostly treated with tenderness and a genuine thrill for being alive:

Lord, the pebbles before my house

have fallen in love with a girl.

The walls light up when she opens the door to me

the books on the shelves begin to dance

and the livid flowers in the vase have started to float through the

air.

Though not a Romanian speaker, I come from another Romance language that tends to preserve Latinate structures, and I had the feeling—maybe mistakenly—that I could peer through the English translation at the Romanian source beneath. Scridon’s poetic rendering seemed to me not so much of a “translation,” a transmigration from Romanian to English, but more of a chemical process in which the poetic material is subjected to pressures and corrosive elements. Once transformed, it jumps out of this primordial ooze anew. Something of the Latinate phrasing perseveres and provides a skeleton to it all, a structure of oddness to accommodate Cristofor’s original poetic universe. It reminded me a bit of Scottish poet Robin Robertson’s translations of classic Ancient Greek tragedies such as Medea: on-point and elegantly strange, something grown out of the original like an extra rib.

Despite being drawn from different collections written over a considerably lengthy timespan, Somewhere a Blind Child follows a coherent design, with themes and characters growing organically, coalescing in a cohesive atmosphere and view of the world—no matter how scattered the view, or how chaotic the world. Words, expressions, images, and situations are allowed to develop through their reiterations, never presenting themselves in quite the same light as before. Though there is no narration, no happy or sad ending, and certainly no answer to any of the urgent questions raised by the poet, Somewhere a Blind Child starts somewhere and ends in some place else, leaving us with the knowledge that we had witnessed and experienced something unignorable.

In the train station of Chitila village

the black angel makes a pit-stop

smokes a cigarette in boredom and leaves.

Get the hell out of here he whispers to me in passing

leave this dreary place.

Your pain has no sisters no brothers

nor a garden of olives from which to hang the noose for your

neck.

Marina D. Martino is a poet and translator. She is currently based in Venice, where she writes, works, and learns a thing or two about water.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: