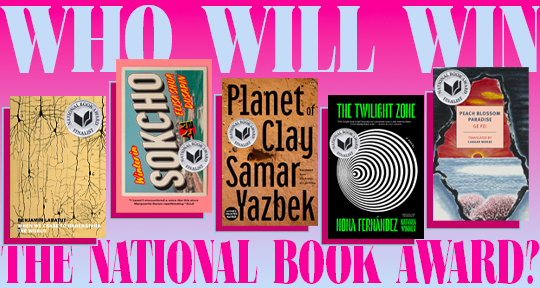

The announcement for the National Book Award for Translated Literature is right around the corner; the 72nd ceremony is due to broadcast live on November 17. On the shortlist are five varied and individual titles: Elisa Shua Dusapin’s Winter in Sokcho, translated from the French by Aneesa Abba Higgins; Ge Fei’s Peach Blossom Paradise, translated from the Chinese by Canaan Morse; Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, translated from the Spanish by Adrian Nathan West; Nona Fernández’s The Twilight Zone, translated from the Spanish by Natasha Wimmer; and Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay, translated from the Arabic by Leri Price. Whom will the judges smile upon? Read more for our take.

A friend, not too long ago, once told me that he feels guilty whenever he reads fiction. Just seems a bit indulgent, he said. Yes, I admitted in turn, when pleasure and beauty mix, it feels incredibly indulgent. It was early autumn, dawn was a glorious thing, and we were talking about the first novels we loved—ones I remember for their intelligent presences, their human authority, but most of all, for the distinct, almost secret, pleasure they brought. The indulgence of excellent fiction feels luxurious precisely because of this intimacy: a sense of understanding passed via that most hidden method, of mind to mind. It seems to me that when pleasure and beauty mix, we allow the precocious lies of fiction to move through us, and become truths.

The five titles that make up the finalists for this award are all, in their own respect, remarkable emblems of fiction’s capability to create truth through duplicity. They achieve this through vivid, personal recollections—as in Planet of Clay—or through intensive research—as in When We Cease to Understand the World—or perhaps in what Borges described as “magic, in which every lucid and determined detail is a prophecy”—something I suspect to be at work in The Twilight Zone. The worlds for which these works contribute their imagination are various, wonderful, horrible, and mercilessly true; it makes me think something else about this triangulation of pleasure, beauty, and truth—that it is in the conciliation of the latter two where the incomparable pleasure of fiction is found.

Beauty is not reliably something one can stand to look at for long, but it always leaves something searing. Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay—the most lyrical and poetic of the five selections—is gorgeously written, and its translation by Leri Price is a definitive work of art, but it feels sick to talk about the pleasures in reading this story of Rima, a young, mute girl in Syria, as she loses one solid fact of her life after another amidst the atrocities and miseries of war. Instead, Yazbek’s prose is a holding thrall, channelling the child’s voice which springs between stark lucidity and dappled abstraction. Elegantly hanging in the balance between the wounded reality and the salve of her reveries, Rima draws an excruciating impression of the pain she experiences and witnesses, intensifying the horror with an unsparing visuality: “I am afraid of the meanings of things when they turn into words, as it is hard for me to understand bare words without turning them into pictures.” The coarse red of blood, the acrid taste of poison gas, the dusty pallor of a face in death—the words of Planet of Clay are both pictures of unflinching witness, and figures of breathtaking reverie.

When We Cease to Understand the World represents a curious fact of fiction—its tendency to swallow up all genres. Benjamín Labatut describes his work as “using the registers of non-fiction . . . and a hell of a lot of research” to (here comes that word again) “reach the deeper truths that only literature can touch and that science really doesn’t have much to say about.” Drawing from the historical inventory where humanity’s majestic forays meet the mystical ideations of chemistry, mathematics, and physics, Labatut expertly builds a dense, labyrinthine architecture of ambition, discovery, genius, and madness. The resulting work is the narrative equivalent to a board covered in evidences of people, places, and things—red twine building up the tenuous, astounding connections and chronologies between them, resulting in the ultimate interrogation into the nature of human curiosity. A seamless translation by Adrian Nathan West only underlines the intricate nature of Labatut’s meticulous novel, which results in one of the most astonishing metaphors concerning the fate of humanity that I’ve ever read in fiction.

“A wondrous land whose boundaries are that of imagination . . .” is how The Twilight Zone—Rod Serling’s sixties-era TV show—opens itself. In potent concoctions of horror, mystery, fantasy, and moralism, The Twilight Zone became synonymous with nothing-is-as-it-seems, providing a perfect vehicle for Nona Fernández’s novel as it inquires into the black holes torn into reality by Pinochet’s ruthless regime. Framed by the narrator’s insatiable obsession with the real-life Andrés Antonio Valenzuela Morales, who confessed in 1984 to committing shocking acts of torture and murder under the appointment of the Chilean army, Fernández tunnels into the cold, mechanical world of dictatorship, which was only just camouflaged by a world in which garbage trucks go by, parents take their children to school, and little boys dream of becoming astronauts. “Imagining, I ask the old trees to speak, I ask the cement under my feet, the lampposts, the telephone wire, the stale air circling this place. Imagining, I bring the bullet holes back to life.” Picking apart the frames and tulle-layers of reality and fabrication, Fernández—in Natasha Wimmer’s intimate translation—displays lie and truth in their tenuous mutuality, proving the imitable power of writing: “Your imagination is clearer than my memory.”

The three titles above affected me deeply both during and in the aftermath of their reading, reverberating around that odd triangle of truth-beauty-pleasure. Winter in Sokcho and Peach Blossom Paradise, which complete the round of finalists this year, did not, for me, meet that same sense of depth and captivation. Though full of moments of haunting beauty (Winter) and surreal mytho-historical enchantment (Peach), Elisa Shua Dusapin’s debut novel of a crystalline winter on the North-South Korean border moved leadenly, as if weighed down by the heavy air of its setting, and Ge Fei’s sprawling reinvention of the Chinese classic in the aftermath of the Hundred Days’ Reform left its heroine lackluster and brittle.

Planet of Clay, The Twilight Zone, and When We Cease to Understand the World are all excellent contenders, and worthy recipients of the Award, but when I think of the state of things as they are, I found myself drifting towards Nona Fernández’s “Imagining, I ask the old trees to speak . . .” I think about all the worlds discreetly moving through the world of our experience, and how fiction coheres all these realities, all these lies that seem like truths, all these truths that seem like lies—and how, perhaps, every spoken truth first appeared in the mind as something of an invention. “You’re moving into a land of both shadow and substance, of things and ideas; you’ve just crossed over into the Twilight Zone.”

—Xiao Yue Shan

In her incisive writing on the 2020 Booker International Prize, Barbara Halla wrote she was hard-pressed to discover a common theme among the shortlisted titles by which to frame her discussion. The five finalists for the 2021 National Book Award for Translated Literature are likewise varied in style and theme, but more explicitly share a concern with individual agency within oppressive conditions created by political upheaval, historical change, or social forces. This common thread is reflected in the overtly political settings of almost all the finalists. Nona Fernández’s The Twilight Zone describes the narrator’s obsession with a member of Chilean Secret Police who confessed to terrible crimes committed by Pinochet’s dictatorship, Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay tells of a young girl’s survival in the midst of the Syrian Civil War, and Ge Fei’s Peach Blossom Paradise follows a teenage girl coping with societal change during China’s Hundred Days’ Reform. These works are joined by Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, which narrates the stories of scientists descending into madness, as they push the limits of human understanding during revolutionary moments in the twentieth century. The last finalist, Elisa Dusapin’s debut novel, Winter in Sokcho, is the least political of the books, but nevertheless concerns itself with invisible social forces, as the woman narrator struggles to be seen in a society that threatens the erasure of her identity. These five books situate their characters against societies undergoing forms of upheaval to ask what power individuals possess to alter their lives against harsh historical and social circumstances.

Dusapin does offer an answer in her quiet yet haunting novel, Winter in Sokcho (an excerpt of which appears in our Fall 2017 issue), lyrically translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins. Dusapin’s storytelling is the sparest in a shortlist with Labatut’s verbal pyrotechnics and the balletic jumps across time of both Fernández and Yazbek. Winter in Sokcho concerns the life of a woman working at a guesthouse in the titular Sokcho—a town in South Korea near the North Korean border. The driving force of the novel is the development of a tense relationship between the woman and Yan Kerrand, a French graphic novelist seeking inspiration. Subtly drawn, the narrative arc suggests a recovery of agency for the narrator, as she ultimately feels seen in her relationship with Kerrand. Dusapin parallels Kerrand’s portrait of a woman with the narrator’s discovery of self. Dusapin’s novel is a personal favorite because of its quiet yet coiled power, its controlled prose, and its refusal to typecast Kerrand as a savior. However, I find it difficult seeing it win because it does not have the political urgency nor the formal inventiveness of some of the other works.

The recovery of silenced voices is central for the writer-narrator of Fernández’s urgent, formally complex The Twilight Zone, fluidly translated by Natasha Wimmer. Fernández’s polyphonal structure links multiple narratives through their relation to the brutal crimes committed by the Pinochet regime, and this structure allows her to give voice to a chorus of victims whose stories have been historically erased. The novel is notable for its self-referential quality, in that it considers both the capacities and limitations of writing and remembrance as methods of grappling with historical erasure. One of the central narratives, that of the “man who tortured people”—a member of the Chilean secret police who confessed to his crimes, testifies both to the possibility of reversing the effects of historical erasure, as well as the long shadow cast by governmental depravity on the past, present, and future. Fernández’s work is a strong contender for its daring structure, its masterful blurring of fiction and fact, and its nuanced grappling with the cover-ups of history.

The individual’s struggle against state violence is the focus of Samar Yazbek’s Planet of Clay, whose narrator’s erratic adolescent voice is expertly translated by Leri Price. The novel’s most notable characteristic is its mode of narration, which is a childlike stream-of-consciousness through the lens of the mute girl narrator, Rima. This narration often drops off threads to start another, which collapses the boundaries of past and present. Rima’s constant writing of memories of dead relatives also suggests the power of artmaking for recording stories that would have been erased by history. However, the mode of narration does sometimes digress from central narrative threads for too long, leading to a loss of tension when they are continued and characters, like Rima’s mother and brother, who don’t feel entirely illuminated. Overall, the book’s stream-of-consciousness is technically audacious but falls short of the completeness of Fernández’s narrative structure.

Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, beautifully translated by Adrian Nathan West, is another work that employs innovative narrative form to probe the agency of individuals confronting moments of social upheaval. Each of the four essayistic portraits show a male scientist broadening scientific knowledge in defiance of longstanding scientific principles; Labatut demonstrates the limits of human action in the face of nature’s complexities, as the scientists go mad upon realizing the impossibility of true comprehension. The essays are accomplished set pieces in themselves, seamlessly blending meticulously researched scientific theory and biography, gripping narrative arcs, and philosophical musings. However, when read together, they resembled complex parables illustrating the same idea in the fashion of a collection, and could have benefitted from a fuller way of relating to each other for the development of their central idea.

Madness and obsession are also central themes in Ge Fei’s Peach Blossom Paradise, translated by Canaan Morse. The book resembles a country house novel, telling the story of Xiumi, a young woman coming of age in a small Chinese town during progressive reform in the early twentieth century, alongside numerous stories of a large cast inhabiting the same crumbling estate. Xiumi’s autonomy is among the most restricted of the individuals across the five titles, as she loses her mad father, is forced into an arranged marriage, and fails to effect any real change in the social reforms she eventually sets upon her town. The novel’s achievement is its skillful interlacing of mythology, history, and character to show the failure of its characters’ utopian ideals in progressing a stagnant society; however, the novel frequently loses narrative focus and momentum by drifting between the stories of its many minor characters, while the translation has a jerky quality, lacking the musicality of West and Higgins’s works.

Although the various characters of each of these works are challenged by prohibitions and limits, they discover freedom through art and writing. Dusapin’s narrator uncovers an identity through Kerrand’s drawings, Rima writes down memories otherwise lost amidst war, Fernández’s narrator clings to documenting a hidden history, and Labatut’s version of mathematician Alexander Grothendieck has gone mad but writes in his diaries until death, seeking an understanding of God. Writing becomes a means of comprehending a hostile, mysterious world. When We Cease to Understand the World most directly explores this theme, and the compelling and innovative way it does so, in addition to its press and resemblance to past winners like the work of László Krasznahorkai, makes it the favorite to win. The Twilight Zone, which is as formally accomplished, also addresses this idea with depth and complexity, and I think it will be a strong contender.

—Darren Huang

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: