In his seminal work on colonialism and subjugation, The Wretched of the Earth, Frantz Fanon asks: “how do we get from the atmosphere of violence to setting violence in motion?” Shukri Mabkhout liberates this idea into story gracefully in his debut novel, The Italian. Delineating the fermenting revolutions in late twentieth century Tunisia through the scope of one young man, Mabkhout paints a vivid reproduction of the oppressive conflicts between nationalism and religion, love and lust, ideology and action. We are proud to present this vivid text, and its detailed contours of individual life in the wider contexts of country, as our Book Club selection for the month of October.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

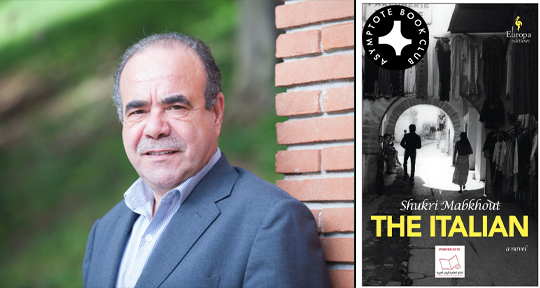

The Italian by Shukri Mabkhout, translated from the Arabic by Miled Faiza and Karen McNeil, Europa Editions, 2021

Shukri Mabkhout’s The Italian, winner of the 2015 International Prize for Arabic Fiction, was first published in the aftermath of the Arab Spring. Perhaps with some suggestion of history repeating itself, it is set during another period of political upheaval in Tunisia—the 1980s and 1990s, which saw a ‘bloodless coup’ led by Ben Ali, the leader who was to be deposed in 2011. Intricate and detailed, heavy with politics, philosophy, food, and sex, the novel is an insight into Tunisian history and society, human relationships, and the often politically motivated and self-interested inner workings of institutional power.

The novel opens with its own violent outbreak and fallen patriarch. At his father’s funeral, the protagonist, Abdel Nasser—nicknamed el-Talyani (the titular Italian) for his Mediterranean good looks—attacks the local imam. The family and wider community are shocked and shamed, but also perplexed; as the narrator, one of el-Talyani’s childhood friends, tells the reader, grief over his father’s death “didn’t fully explain it.” Abdel Nasser’s family members offer various explanations—the “corrupt books” he read as a child, his university classmates, the personal circumstances of his divorce, or the “deep-rooted corruption” of his morals. While the broader community simply consider him the black sheep of the family, none of these explanations seems to satisfy the narrator. Jumping back in time, the novel thus sets out to unpack what might have motivated Abdel Nasser’s outburst, and, along the way, also details much of the political history of Tunisia during these tumultuous decades.

Abdel Nasser has a complex and somewhat distant relationship with his family, and in particular with his brother, Salah Eddine. Salah Eddine left Tunisia as a young man, and is now an “esteemed academic and international finance expert” living in Switzerland—in other words, he is the epitome of cosmopolitanism and institutional economic liberalism. When Salah Eddine leaves Tunisia, Abdel Nasser assumes the throne as the de-facto eldest son—which Mabkhout explains endows a special status and freedom within the Tunisian family. He also takes up residence in his elder brother’s room, which provides him with an intellectual awakening through books and records, and in which he also experiences a sexual awakening: he is groomed by the family’s significantly older neighbour, who—by no means coincidentally—is his brother’s ex-lover. The room eventually also becomes a political hotbed where Abdel Nasser discusses philosophy, politics, and Marxist economics with select classmates, for he is set apart from others not only by his good looks, but also his astute mind and leadership skills. He goes on to study law at university, where he acts as a leader and recruiter in an activist student organization.

The 1980s in Tunisia saw the growth of social protest by trade unionists, students, and Islamists, and the novel depicts this through Abdel Nasser’s involvement in a leftist student syndicate. The group is staunchly against the present regime, and it also clashes both intellectually and physically with a student Islamist group, as well as with the police. Much of the first part of the novel details the internal and external politics of el-Talyani’s university days, with detailed depictions of the tactics and very academic discussions of his group’s power structures, philosophy, and goals. Some of this may feel somewhat dry to the average reader, especially for those not steeped in the philosophers and theorists of the era or in Tunisian history, but—at least in terms of the latter—the entire novel provides fascinating, detailed information, and can be a great jumping-off point to learn about the complex political and social backdrop of this former colonial North African country.

The academic flavour of the novel’s many political discussions is unsurprising—and not just because of how much of the novel is set within and around the university. Shukri Mabkhout, born in 1962 in Tunis, is an academic who had already published widely on literary criticism before The Italian—his debut novel—was released in Arabic in 2014. He is now president of Manouba University, and, although this university—where he also attained his PhD—is not the same as that depicted in The Italian, he would have been a student at about the same time as the fictional Abdel Nasser. The novel’s detail lends it a veracity that makes it easy to assume that the writing is informed by what Mabkhout may have witnessed himself, and, given the depth of academic knowledge in its philosophical and political subject matter, worked on as a researcher. Like Mabkhout, the translators Miled Faiza and Karen McNeil also have academic backgrounds, and their co-translation is precise and fluid, like the story itself. They work to retain some of the flavour of the original Arabic language by transliterating certain Arabic terms and providing a glossary, which serves to deepen the reader’s cross-cultural knowledge while maintaining a seamless reading experience.

While recruiting and campaigning for his political organization at university, Abdel Nasser at first butts heads with, then falls for Zeina, a brilliant student of pure philosophy who, while considered part of the leftist movement, refuses to become involved in day-to-day politics. Zeina lives in a kind of academic fortress, abstracted from everyday life, but she is forced to engage with it and compromise her desire for true freedom and impartiality by marrying Abdel Nasser—in order to continue pursuing the professional career she so longs for. Despite their passionate lovemaking, she remains distracted by her career and emotionally detached, and eventually Abdel Nasser becomes a kind of Don Juan, having affairs with people close to Zeina as well as complete strangers. The contrast between theoretical discussions of politics and philosophy and quite explicit sex scenes makes The Italian almost a Tunisian, post-modern D. H. Lawrence, although the way the sex is depicted is much less veiled than anything in Lawrence.

The gender and sexual politics in The Italian are at times ambiguous, challenging, or both—especially when viewed through a Western moral lens. Tunisia, as portrayed in the novel, seems—at least through my Western gaze—simultaneously modern and conservative. Laws inflected with religion (such as being unable to get a marriage certificate without converting to Islam) and quite strict gender hierarchies are depicted alongside sexual openness and a support for gender equality in the public sphere. Abdel Nasser champions women’s rights at a political level, yet maintains an expectation that, at home, Zeinab should fulfil his expectations of femininity. Sexual freedom seems to be supported, and Abdel Nasser certainly exercises his rights to it, but holds his wife to the double standard of being faithful, and even criticises one of his former lovers as a “a body without a soul, an instrument of pleasure for those who requested it . . . a card-carrying professional prostitute” when she chooses to mingle with the rich and powerful. Parallels can be drawn between Abdel Nasser’s description of this ex-lover and the way in which his mentor and editor-in-chief at the state newspaper (where they are all “just cogs in this great . . . machine of spreading lies and futility”) describes Tunisia itself:

The country was no stranger to being conquered: Carthaginians, Vandals, Romans, Shiites, Khraijites, Banu Hilal, Turks, Spaniards, French—they all subjugated it. It experienced some pain but embraced them with a welcoming heart. Despite the veneer of conservatism and religion, it kept up its prostitution and asked for nothing but protection.

It seems that, while the situation for women may have shifted, their freedom must remain curtailed: “a woman’s freedom in Tunisia was limited to the freedom to choose your master; it didn’t allow you to choose your life.”

In one quite powerful MeToo moment, Zeina—who has fought so hard to choose something different from the life she was born into—is given a failing grade from a professor whose romantic advances she had previously rejected. The university offers her no recourse to lodge a complaint or have her paper re-examined, since “to require [a second grading would] cast doubt on the integrity of the professor,” and the dean she speaks with tells her, “I have no problem believing you, but me believing you has no meaning from an administrative point of view,” suggesting instead that she apologise to the professor who harassed her. This injustice is cast in an unambiguously negative light by the narrator, but the novel’s stance on what follows is much more ethically questionable; when Zeina finally gets the divorce from the marriage she never wanted and settles down with a French academic three times her age, the narrator’s verdict is that she cannot be sexually satisfied and would have had a better fate had she stayed with Abdel Nasser. While there is clear sympathy for her plight, Zeina is nevertheless seen as responsible for her own downfall—as one of the “intelligent people [who] sometimes crushed themselves, if their ego was big and their ambitions bigger”—and is reduced to a symbol of her national circumstances: “It’s a sad story that confirms that this country . . . pushes its children toward destruction and loss; it eliminates the brightest among them or grinds them down until they’re just like everyone else, or worse.” While there is some sense of critical self-awareness in the narrator’s description, he ultimately depicts Zeina as a “plaything” for her new partner—as, in a sense, she was for Abdel Nasser. Time and time again in the novel, sex and power coalesce, and women are described in subordinate terms: they are princesses, queens, “earth preparing to be tilled,” prey, or horses to be ridden and reigned in, while men are bulls, riders and huntsmen.

The effect of this gendered language can be quite jarring, yet it would not be fair to simply dismiss the novel as sexist, especially as women are far from the only victims in this tale. Everything we read in The Italian is filtered through the narrator, who has presumably heard all the details from various sources, including el-Talyani himself, and much is written as reported speech, which creates an additional distancing effect. These layers of reportage make it hard to discern a definitive political or moral position, and the parallels with Abdel Nasser’s later career in the newspaper industry, with its (self- and state-enforced) censorship, propaganda, and intentional framing, is surely no accident.

As well as providing insights into the specificities of its historical context and entertaining through its love story, the novel lends itself to debates on more universal themes such as power, corruption, the idealism of youth, gender equality, and abuse. Abdel Nasser is a complex and multi-faceted character: like so many people, he is noble yet flawed; he has wronged and been wronged. The Italian—both the novel and its eponymous character—thus prompts us “to think outside of the fatal dualism of faithfulness and cheating, good and evil, justice and injustice, love and hate,” and it certainly forces us to think beyond the dualism of victim and perpetrator, and carefully weigh the possible roots of a situation, even while we may condemn the fruits these roots bare.

Ultimately, The Italian ends where it begins: with the funeral and Abdel Nasser’s outburst. While the novel offers personal, traumatic circumstances that sufficiently justify Abdel Nasser’s actions, the personal seems secondary to the political in The Italian, and the sexual relationships in the novel can perhaps be read symbolically as representing the politics of impotent abuse and seduction wielded by an apparatus of power over its subjects. The novel provides few clues as to whether these conditions—for women, Tunisia, and the world—will improve, or if the power structures have been incorporated too completely, doomed to be repeated. Perhaps, as Abdel Nasser’s mentor tells him, the state and society are so much a part of us as to be inescapable:

The state is the biggest lie that humanity has ever created and then believed in. The state is me. And you. And the secretary who gives me her body in the office, without me asking for it, because I represent the state in her eyes. We’ve known since antiquity that the state is omens and signs but is intangible. It’s a hidden god: no one has ever proved its unseen existence, so they both love it and hate it.

But let’s hope not.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English. She has worked as a teacher and researcher in Germany and the UK, and is currently based in Australia, where, alongside her translation work, she volunteers as a copyeditor for Asymptote. She holds a Master’s in translation, and in 2016, won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: