This essay is written in memory of all those—predominantly Algerian—killed, deported, or otherwise injured by the violences of French colonialism, and in solidarity with the continuing efforts to resist the forgetting of October 17, 1961 and demand accountability from the French state.

For most of the English-speaking world, October 17 will not register as a date of any consequence. Yet, several days ago in the boulevards of Paris, scores of demonstrators marched from the Rex Cinema to the Pont Saint-Michel; they were tracing, in a defiant act of memory, the cartography of a heinous massacre of Algerian protestors by the French police force that took place, sixty years prior on the very same cobblestones. Their ancestors—most of whom did not survive that deadly evening—had walked those roads in peaceful opposition to the racism and surveillance they had suffered at the hands of the French, as well as the discriminatory night-time curfew that had just been imposed exclusively on Algerian workers.

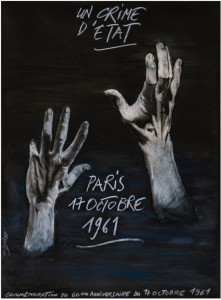

The publicity posters of this year’s commemorative efforts feature the title “Un Crime d’État” (a crime of the state), handwritten in a ghostly chalk-like texture above two shadowed hands reaching out of murky, watery depths. To the survivors, descendants, relatives, historians, activists, and those who otherwise refuse to forget the bloody police brutality of October 17, 1961, that tableau of desperation will be familiar. On that night, besides beating and injuring countless men, French police officers handcuffed and threw an undocumented number of Algerian demonstrators into the river Seine, leaving them to drown. Historians estimate that around two hundred deaths occurred that night. In an eyewitness account cited in House and MacMaster’s monumental Paris 1961: Algerians, State Terror, and Memory, officers throttled the arms of a man clinging to the parapet “until he dropped like a stone into the river.” Subsequently, nearly six thousand Algerians who did not perish were rounded up, tortured, and deported back to detention camps in Algeria.

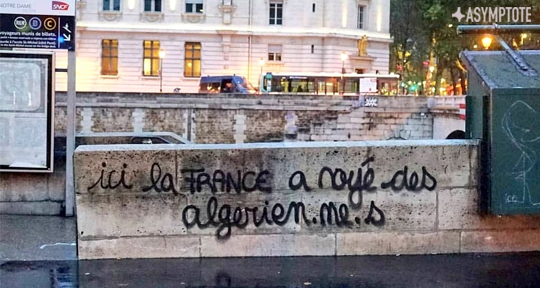

Of the scant images that have circulated of 1961, the most iconic is arguably a shot of graffiti spray-painted along the riverbanks, reading “Ici on noie les Algériens” (here we drown Algerians). What’s remarkable is its persistent afterlife in the infinitely reproducible medium of photography, elevated to a sort of metonym for Algerians’ collective trauma—despite the actual graffiti having been literally whitewashed out of existence not long after its writing. Street art continues to spring up here and there: a telling instance is “Ici la France a noyé des Algérien(nes)” (here France drowned Algerians), shifting the temporal frame of reference and naming the locus of guilt. Or, more recently: “Nous sommes les descendants des algériens que vous n’avez pas noyé . . .” (we are the descendants of the Algerians that you did not drown).

The state’s erasure of the incriminating graffiti emblematises an essential hypocrisy upon which France’s modernity is built, and perhaps no colony has borne the brunt more painfully than Algeria. It was there, during its struggle for independence from 1954 to 1962, that the French government engaged in one of its most violent and cruel wars while native peoples agitated for decolonisation. Yet the metropolitan French press, largely indifferent to what was transpiring across the Mediterranean, referred to the widespread killings, bombardments, and torture euphemistically as “the events.” Only in 1999—a full thirty-seven years after Algeria gained independence—did France officially bring itself to acknowledge that a “war” had occurred.

France has habitually dealt with its crimes by pretending that none of it ever happened. In the wake of October 17, the relentless forgetting enforced by the state is similarly paradigmatic. The authorities imposed pervasive censorship, confiscated books and films, and vociferously denied that the police had massacred innocent civilians. Demands for accountability and restitution were delayed and effectively rendered useless when, during the Evian Accords of 1962, amnesty was granted to the war criminals on France’s side. Jacques Panijel’s Octobre à Paris, the first documentary film to be made about October 17, was banned until 1973 (twelve years after the pogrom). For the next few decades—and it is difficult to imagine how immense the collective conspiracy needed to be in order to sustain this silence—hardly anyone dared speak about it, out of fear of reprisal. Police archives were locked for fifty years, all the way until 2011.

Crucially, though, one runs the risk of losing sight of the wider, far more insidious context of French colonialism (and ongoing neo-colonialism) in focusing on a single date. Cycles of violent killings were, indeed, already commonplace and normalised on Algerian soil; the Sétif massacre of 1945, for instance, represents but one culmination of French repression. In this light, October 17, haunting as it may be, cannot be seen as exceptional in any regard. It marks a turning point only to the extent that it occurred in the very heart of France’s capital, and exposed the Enlightenment ideals of humanism and universal equality as myth, to a degree of unparalleled visibility. One finds it all the more shocking, then, that despite the sheer luridness and ubiquity of the killings, the French state succeeded in burying the date under a thick patina of forgetting. Unlike other acts of state terror (like Charonne in 1962), October 17 lacks a name. Known only by the date on which it occurred, the day has become more potent and opaque as a symbol within the circularity of calendrical time, returning us over and over again to the effaced scene of devastation.

It is within that cultural lacuna that the scholar Lia Brozgal theorises the “anarchive” of October 17 in her groundbreaking book, Absent the Archive: Cultural Traces of a Massacre in Paris, 17 October 1961 (to which my article is indebted). Surveying a wide range of novels, films, songs, and plays, she makes the point that “literature and culture may ‘do history’ differently (. . .) by functioning as first responders and persistent witnesses; by reverberating against reality but also speculating on what might have been.” Tethered to the archive yet constantly straining against its omissions, this body of (predominantly Francophone) work contours the impossibility of receiving adequate justice, in any measure, from the law and the state.

Notably, the canonical Algerian writer Kateb Yacine’s poem, “Dans la gueule du loup” (In the jaws of the wolf), composed in 1962, was one of the first cultural artifacts to memorialise October 17—also enjoyed a mild resurgence when the rock group Têtes Raides set it to music in 1998. Addressing “the French people” directly, the poem functions as a rousing rallying cry, exposing overarching similarities between the massacre and the “own revolutions” of the “Parisians.” Its ending salvo implicates the complicity of French society: “people of France, you saw it all . . .”

A two-decade-long period of oblivion would pass before the first French novel referencing October 17 would appear, in 1983: Didier Daeninckx’s Meurtres pour mémoire (translated by Liz Heron as Murder in Memoriam), a pulpy detective novel that retains its popular status today. Set in the municipal archives of Toulouse, the story foregrounds the sleuthing in history, following the detective protagonist Cadin as he investigates the murder of a father and son—the latter of whom is killed in the bloodshed of October 17.

Leïla Sebbar’s La Seine était rouge (translated by Mildred Mortimer as The Seine Was Red), released in 1999, marked a significant shift in cultural and literary discourse, as it unprecedentedly dedicated its whole narrative project to the memory of the massacre. Charting the mutually enmeshed trajectories of three different characters with varying degrees of investment in October 17, the novel explores how trauma can be mediated by cinematic images and re-inscribed in physical space—calling to mind Léopold Lambert’s chrono-cartography of the massacre. The characters, traversing the urban landscape of Paris, write over solid monuments and commemorative plaques with vanished stories and histories, treating the city as a palimpsest and bringing to light what Brozgal calls “a zone crackling with invisible semiotic traffic.”

That many works of fiction remain untranslated from the French perhaps reveals the continued invisibility of October 17 in Anglophone spaces. These include notable titles such as: Mehdi Lallaoui’s Une nuit d’octobre (A Night in October), which takes inspiration from high-profile trials brought against Maurice Papon, the chief of Police, in the 1990s; Nacer Kettane’s Le Sourire de Brahim (Brahim’s Smile), a novel that opens with—and remains haunted by—the murder of the titular character’s brother amidst the police crackdown; Tassadit Imache’s Une fille sans histoire (A Girl without History), which grapples with the massacre’s afterlives and the racial profiling to which the French police continually subjects Algerians and North Africans.

Films like Faïza Guène’s Mémoires du 17 octobre 1961 and Yasmina Adi’s Ici on noie les Algériens—structured by eyewitness accounts (significantly given in Arabic rather than French), and plays like Aziz Chouaki’s La pomme et le couteau (The Apple and the Knife), also testify to the importance of oral history and embodied cultural forms in the remembrance of trauma and erasure. Chouaki’s theatrical piece enacts the experience of drowning, evoking the river Seine mainly through sound. The massacre is also commemorated in performance art—Memento, a piece by Komplex Kapharnaüm, travelled from city to city dramatising the arrest and killing of innocent Algerians, symbolised by the silhouettes of their bodies negatively imprinted in a wall after being bombarded with a paint gun.

What can we look forward to this year, the sixtieth anniversary of the pogrom? A hip-hop ballet choreographed by Mehdi Slimani entitled Les Disparus (The Disappeared), reprising the scene of Algerian bodies being flung into the Seine, is being restaged. A documentary by Ali Fateh Ayadi, made as a gesture of homage to Fatima Bédar—one of the few female victims, and the youngest among them—was screened in Saint-Denis. The troupe Théâtre Par Le Bas in Nanterre performed their play Je me souviens (I remember), in which the lead actor M’hamed Kaki recounts the night to his granddaughter. French-language documentaries have proliferated: a conversation between a historian and a journalist about the long journey towards reconciliation and reckoning, and even a film about Saïd Abtout, one of the last survivors of the massacre.

More accessibly for English readers, France 24 has published interviews with several bystanders and survivors, and New York Review Books has reissued William Gardner Smith’s pioneering, and long out-of-print The Stone Face. Written in English, Smith’s semi-autobiographical book portrays an African-American journalist disillusioned in Paris by the French government’s treatment of Algerians, and, interestingly, is the first novel in any language to make reference to the events of October 17.

The demonstrators in Paris this year have demanded, among other things, a public acknowledgment of the state crime from the President, a collective recognition of the Algerians deported to death camps after October 17, and the creation of a memorial site for the trauma. But one wonders how much confidence can be had in a state that has repeatedly frustrated and disappointed us. How will France reconfigure its fragile self-image to accommodate the historical excesses that it has consistently balked at confronting? Emmanuel Macron might be the first President in the Republic’s history to attend the public ceremony at the Bezons Bridge, but how do we square this with his recent comments that egregiously exonerated the French state and deflected blame solely to the chief of police Maurice Papon? And what of his remarks about the non-existence of an Algerian nation before French colonisation? If these gestures were to be performed, would they be anything more than a perfunctory spectacle, given France’s ongoing race-obliviousness, Islamophobia, and neo-colonialism?

It is furthermore unbearable to learn that access to the Pont Saint-Michel was entirely blocked by the French police this year. While the Prefect of Police made a big show of tossing flowers into the Seine, none of the demonstrators—the people for whom the massacre actually holds significance—were permitted to do the same. It is difficult to overstate the utter hypocrisy of this gesture. Every year, October 17 has been memorialised by survivors, descendants, relatives casting bouquets of roses into the site of mass drowning—even that seems to have been taken away.

But while France reddens and flounders in the face of its own history, baldly disavowing its participation in indisputable crimes, there are those who know where to look—who insist on holding onto the evanescent redness of lives lost in the Seine and on the cobblestones of Paris, to the senseless brutality of the French state. As Hadda Khalfi, an Algerian widowed by October 17, intones in Yasmina Adi’s Ici on noie les Algériens, addressing the river Seine directly: “I know that you are there in the water. (. . .) You will always be here.” Ghennoudja Chabane, another survivor, recounts how she rallied the women around her, asking those with lipstick to draw the Algerian flag on impassive cement walls. The people mourn, together, and in the interminable interim perhaps simulate for themselves something like justice; we have not forgotten, and we will not cease to rewrite, October 17, 1961.

Photo source: Twitter

Alex Tan is a writer, aspiring translator, and student of comparative literature at Columbia University, with a particular interest in the literatures and language politics of Southeast Asia and the Maghreb. They currently work with Transformative Justice Collective in Singapore, and serve as Assistant Editor (Fiction) at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: