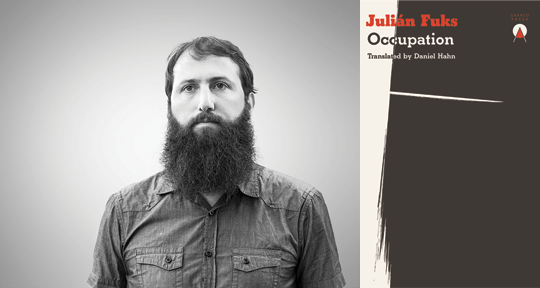

Occupation by Julián Fuks, translated from the Portuguese by Daniel Hahn, Charco Press, 2021

I’m writing a book about fatherhood without being able to become a father—and probing motherhood as if I didn’t know that I will never learn it. I’m writing a book about death without ever having felt it switch off a body, in a speculation of feelings that one day will seem laughable, when I do encounter the pain. I’m writing a book about the pain of the world, the poverty, exile, despair, rage, tragedy, ludicrousness, a book about this interminable ruin surrounding us, which so often goes unnoticed, but as I write it I am protected by solid walls.

Occupation, Julián Fuks’ latest novel to appear in English translation by Daniel Hahn, is a quiet masterpiece. Touching on family and relationships, birth and death, colonialism, the refugee crisis, political activism, the Holocaust, our (in)ability to identify with one another, and how to find hope in a world of ruin, this novel is sweepingly ambitious in its themes, yet the measured, self-critical voice of the narrator and the calm, understated prose prevents it from veering into sensationalism or sentimentality.

The novel’s chapters alternate between the different preoccupations of our narrator, Sebastián: his father, who is occupying a hospital bed; his wife’s decision to have a child, which will occupy her body and shift the dynamics of their relationship; a group of migrants occupying a dilapidated building, many of whom exiles from lands that have been occupied, now seeking refuge in Brazil, a country with its own history of occupation; and his own attempts to understand what all of this means for his occupation as a writer.

Small jumps in time, along with chapters that begin mid-conversation, can at times create a sense of dislocation, but Fuks weaves the strands together so gently and dexterously that when they coalesce, it does not feel like the technique has been a pretext for creating suspense; rather, it is as though the narrative has been constructed this way so that the narrator might himself work through and better understand the components—as if each narrative thread must be understood on its own to bring the whole into relief. Nevertheless, the technical mastery of this construction should not be downplayed, and throughout the book, the reader will notice explicit motifs along with subtle echoes and patterns in the language. All this adds to a sense that the novel’s threads are both connected and discreet, amplifying the plurality of the voices and experiences which ultimately merge with the voice of the narrator, who “allow[s] them to occupy [him], to occupy [his] writing: an occupied literature.”

Other than his own, highly relatable experiences about the spectre of losing a parent and the struggle to become one, the stories with which Sebastián fills his pages are told by the residents of the Cambridge, a former hotel that is now a squat for refugees of all kinds. The stories from Najati—a Syrian exile who first brings Sebastián to the Cambridge—appear most frequently: we hear of the family he has left behind; stories from his time in prison; “everyday trivialities that [reveal] the vastness of the misery;” and poignant, yet almost comic, accounts of his interactions with his oppressors:

Najati described how they liked to surprise, in that same garden, the secret agents who were supposed to be following him from afar, breaching the regulation distance and sitting with them on the lower branches beneath the trees. They ended up engaging in lengthy discussions, which never failed to reveal something of the humanity of those agents, good young men when stripped of their uniforms, hardened by the cruel practices their duty demanded of them.

We read the tales in Occupation through the filter of many different voices—the refugees; the narrator; the author, Fuks himself; and, for the English reader, the translator, Daniel Hahn—and we are also constantly reminded that what we are reading is a carefully constructed and self-aware piece of metafictive autofiction. The “mask” of fiction sometimes slips, as in an instance when the father calls Sebastián “Julián” in a moment akin to the breaking of the fourth wall:

Dad, I’m going to have a child. That’s such lovely news, Julián. Thank you for telling me. No, dad, thank you. But here you’ve got to call me Sebastián.

Or when he calls his wife by the name of Fuks’ actual wife:

Fê, I called out to her, with a timidity even I didn’t recognise. Please, don’t use my name, it wouldn’t be fair, that’s not what I’m like, she rebuked me.

Is what we are hearing here the real-life Fê, commenting on her fictionalised alter-ego, or is this the author’s admission that the image he has created of his wife, either in literature or in life, is precisely that—an image? Julián Fuks’ hyper self-referential novel constantly questions such distinctions between fact and fiction, both on and off the page, and blurs the boundaries between narrator and author, confusing—in Najati’s stories, as we do in Occupation itself—“the story’s narrator or the writer of the article.”

Sebastián shares many autobiographical qualities with Fuks: both “write about exile” (for the latter, this has previously been in the multi-award-winning Resistance, also translated by Hahn); both have psychiatrist parents who fled Argentina for Brazil; and both have grandparents who before this fled Europe for Argentina. It is only part-way through the novel that we learn of Sebastián’s great-grandparents’ death in Auschwitz, and the timing of this revelation jolts the reader just as it does Sebastián. This is the first time the reader learns of his Jewish past, and for Sebastián, despite knowing that his grandparents had died in the Holocaust, “the name Auschwitz, with its cultural burden, with its power to evoke a vast gallery of accounts and images, seemed to give the fact an inescapable concreteness.” This added historical dimension to the themes of victimisation and exile, along with the measured, clear tone and the inclusion of presumably real letters from Mia Couto—a Mozambican author who has worked with Fuks—brings to mind another literary masterpiece that also plays with the border between fact and fiction: W.G. Sebald’s Austerlitz. But Sebastián’s new concrete knowledge about his family’s experience in the Holocaust, along with his family history of fleeing Argentina, also leads him to question the extent to which he can identify with the refugees in the occupation. On reading names scratched into the wall of a new squat, he writes:

Everywhere I read names as though by doing so I could pay them some respect, show my pity for the victims, just as I had once done before the wall of those who had been transported to the camps, or the disappeared in Latin America. But now I had no name to look for here, none of my people had suffered in this building, these names were all unknown to me. And I learnt then that I could not exempt myself, that I could not ally myself to the multitude of victims, and once again I felt the anguish or the nausea, the unnameable thing that was flowing towards my chest, much more intense.

Throughout Occupation, as the narrator struggles to “look into the eyes of others to seek something other than [his] own reflection,” we feel the tension between the singular and the universal, and between giving voice to others and appropriating those voices. At one point, the narrator loses the recorder and notebook he has been using when speaking with the residents of the Cambridge, and self-critically reflects on why he might have done so: “I, an onlooker, an intruder, a mole. I, a looter of stories, stealing from these people, their eyes, their hands, even their voice. I think that was where I left my recorder behind, as if by doing that I might get rid of the evidence incriminating me.”

Yet the imperative of sharing other people’s narratives, of searching to understand both himself and the storytellers through them, compels Sebastián to chronicle his versions of them nonetheless, and this variation on—presumably semi-fictionalised—oral history brings to mind Svetlana Alexievich’s brilliant Secondhand Time. A better understanding of other people is one of the reasons we read world literature and translations, but as much as we may aim to broaden our horizons and lose ourselves in other worlds, part of the utopian catharsis of art is lost if we are unable to identify with aspects of the narrative or characters. This autofictional novel helps us tease out and probe these issues via the narrator’s attempts to see others without merely seeing himself.

Through the various traumas depicted in Occuption, this book thus asks whether we can ever fully surrender ourselves to the perspectives and needs of others. It contains much darkness—the ruins of Syria; the ruins of an ageing, ailing body; the ruins of a building; of ancient Central and South American civilisation, replaced by modern “civilizational failure”—but while there is grief and loss, and a constant threat of further personal ruin or failure, some of the darkest clouds hanging over the narrator ultimately clear, and the novel itself does not leave the reader ruined. Hope remains, even if what we are offered is a tentative kind of salvation. At least one ruined building becomes a home for those who need it; the father does not yet die; Sebastian’s relationship with his wife does not fall apart, and a new life may yet come to occupy their home; Sebastián manages to “merge into the vastness of others”; and we are left this thoughtful, thought-provoking book. As one of the Cambridge’s residents implores of Sebastián, Fuks has “put something more than pain, something more than misfortune” in his novel, making “something worth writing.”

Sometimes it’s hardest to write about the books that you most enjoy and admire, that you most want others to read, and writing on Julián Fuks’ Occupation has been a case in point. Perhaps the difficulty can in part be attributed to the multiple threads of its narrative, the sophistication of its language—translated so seamlessly by Daniel Hahn—the universality and importance of its themes, and its potent mixture of grief and hope. With its masterful inquiries into identification and occupation, this novel is bound to find a home in the wide-ranging imaginations of its readers—in yours as it has in mine.

Rachel Stanyon is a translator from German into English. She has worked as a teacher and researcher in Germany and the UK, and is currently based in Australia, where, alongside her translation work, she volunteers as a copyeditor for Asymptote. She holds a Master’s in translation, and in 2016, won a place in the New Books in German Emerging Translators Programme.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: