In Carolyn Forché’s poem, “What Comes,” she writes: “To speak is not yet to have spoken.” Amidst the myriad of voices clamouring to be heard today, writers often aim to reconcile the journalistic motives of witness and the cultivated balance of narration, bringing the scattered language of a society into a solid, comprehensible whole. The best of these texts has proven to be a powerful tool in re-establishing the broken links between people living under a regime, and in a newly released book from Thailand, an anonymous writer seeks to do the same in a fascinating and deeply probing exploration of the country’s strictly enforced lèse majesté laws.

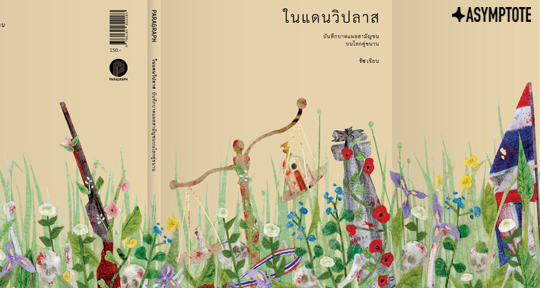

What can literature do during times of emergency, wherein testimony takes precedence over much of storytelling? This year in Thailand, amidst the ongoing crackdown on anti-government protesters—exacerbated by viral outbreaks in prisons—witness accounts by lawyers and journalists have assumed the task usually assigned to literature: to describe the human condition and to build conscience. One particular book, however, has managed to straddle the worlds of journalism and literature. A collection of anecdotes about those affected by the lèse majesté law in the 2010s, ในแดนวิปลาส (In the Land of Madness, Paragraph Publishing, April 2021), has much to teach us about how to tell the stories silenced in the throes of oppression and censorship. It is anonymized yet revealing, packed full of pain but with surprising touches of humor. Perhaps due to its relevance to current events in the country, the book has seldom been considered as a literary object. Yet, in its description, the book categorizes itself as a “Thai novel.” This gets my puzzle-solving mind turning.

One might read the categorization as ironic, and—taking “novel” to mean fiction—come to the truism that, in the Kingdom of Thailand, the truth surrounding the monarchy and its victims must, for reasons of safety, make itself anonymous, dressed up as fiction. But reading the label as a genuine attempt to define itself may yield deeper and more surprising insights. In the author’s preface, a line is drawn between reporting based on facts and storytelling based on feelings:

All the stories in this book grew out of prying curiosity indeed. Half of its fruits became serious news and information while I worked as a journalist in a small but big-hearted news agency; the other half turned mostly into emotions and feelings I put away in a bag and didn’t know what to do with.

In a situation where rights and liberties were repressed for a long time, where injustice was standard practice, the bits and pieces being collected in my bag kept getting heavier and heavier, to the point where the bag seemed to be bursting. There were two parallel worlds. People lived normal and bright lives in one, while the other was pitch dark, cruel, and noticed by very few. One stranded between the two worlds would therefore find it extremely difficult to maintain one’s sanity and normalcy.

It isn’t that fact and feeling are necessarily opposed; rather, the preface suggests that there is a remainder left over from the work of journalism—that certain parts of a journalist’s experience can only be stored as feeling and emotion. Shining the “spotlight” on society’s darkest corners provides only one aspect of reality. The other sides—unspoken or unspeakable, unborn or unbearable—are best accessed via novelistic means. In the Land of Madness definitely ‘reads like a novel’ in the sense that it is a well-crafted, compelling story wherein some characters are depicted with vivid inner lives, whereas others remain unknowable despite their palpable presence on the page. Calling it a novel also allows for some artistic license, a deviation from factual description to get at a deeper truth; in the book’s most surreal moment, the narrator notices a friend’s “internal” injuries by seeing lances of sunlight piercing through holes in his frame.

Despite its urgency, the book is quiet and unassuming; it nestles in the reader’s arms, full of mysteries and secrets. Every so often, a key bit of information drops. The reader doesn’t know, for instance, that the narrator is a woman until halfway through the book—when all of a sudden there’s an anecdote about using the pronoun noo, which conditioned her to appear meek and childlike. (A man can use pom to refer to himself politely in Thai, with no baggage of hierarchical relations—no such luck for non-men.)

Another puzzle is the author’s pseudonym. While one can easily find out or deduce her identity (there aren’t many journalists devoted to covering lesè majesté cases in my “small country” of approximately seventy million), in order to decipher the pseudonym รัช, one must turn to the dictionary: derived from Pali, it means king as well as dust. In Thai dissident lingo, “dust underfoot” (ฝุ่นใต้ตีน) refers to common people; it is a colloquial rewording of the ceremonial pronoun which commoners use to address the king via the dust under the soles of his feet—to “translate Thai into Thai again,” as we say. This ironic accident of etymology recalls the 1932 revolutionaries’ memorable retort to the absolute monarchist claim that commoners were (and are) still too foolish to exercise political power: if the people are dumb, then royalty must be dumb too, for both are cut from the same national cloth.

The namelessness extends to everyone in the book. While it is not too hard for a well-informed Thai reader to identify many of the people mentioned in the text, the anonymous presentation does put them under a new light—or a new darkness, if you will. Without proper names headlining each person’s story, numbered subsections develop patterns of commonality, avoiding the pigeonholes of heroism, victimhood, or ideology in the reader’s mind. Each subject is shown facing a difficult choice where there are no right answers, although—as it turns out—there definitely are wrong ones.

Take, for example, the weaponization of rage against injustice. A poignant case is a survivor from the 2010 Bangkok massacres who, “unfortunately could not channel his rage into poetry, art, scholarship, analysis, or witticism on social media like others.” Instead, he turned to a home-made bomb, which someone asked him to place in front of a political party headquarters. Devastatingly, that bomb exploded on his face and destroyed all chances for sympathy and support afforded to “prisoners of conscience.”

The splitting of the world into two parallel dimensions implicates all spheres of society—especially the media. The unblemished happiness of the many depends on one little thing—the truth—suffering out of sight. In one of Ratch’s anecdotes, she was sent abroad to interview political exiles who referred to King Bhumibol’s name nakedly, without honorifics. That feature story about otherwise harmless people ended up too dangerous to publish in Thailand. The exiled dissidents’ way of thinking and speaking was deemed unspeakable no matter “how light, how normal, how agreeable, how multi-dimensional” she tried to portray them.

An experience of self-censorship by progressive media affects the tone of Ratch’s prose, torn between prudence and the need to share. Many times, she begins a sentence with: “Nobody knows.” In certain instances, she’s about to impart something she knows; but then, there are times in which she doesn’t—as in the case of an exile’s autopsy results: “Nobody knows in what order it happened, between cutting open the belly, strangulation, and beating the face to a pulp.” In the face of such uncertainty, Ratch imparts instead the knowledge of the various ways people have chosen to deal with it. Some believe statements from scientific experts, others seek second opinion from spirit mediums and fortune tellers, while still others choose not to investigate at all.

In sharp contrast to the anonymity are the three chapter titles, which announce their keywords in boldly visible typeface: พ่อ (FATHER), ไพล่ (TWIST), and พายุ (STORM). Such are the three monstrosities looming over innumerable specks of dust: the king as the semi-divine father figure, ironic twists and turns in the labyrinth called the justice process, and violent storms of military repression. Indeed, they are the setting for the book’s characters. All three seem inhumanly powerful, yet derive their potency from all-too-human relations. The Wrath of the Father, for example, manifests in the form of angry ultraroyalist mobs. The setting’s pressures on the characters make for all sorts of dramatic conflicts: from man versus family and ideology, to (wo)man versus society and God.

Despite the gloomy subject matter, the narrative is imbued with an “ambitious hope” for the next decades. Ratch points to the continuity of a revolutionary spirit that, like “spores of prehistoric ferns,” drifts undetected, only to reemerge and unfold at another place in another time. Demonstrating the case in point are the groundbreaking protests for monarchical reform in 2020—which nobody predicted. They yanked open the doors for open discussion about the lèse majesté law in mainstream culture, perhaps predicating that the parallel worlds have converged in some way. Yet, the bifurcation remains in operation, as evident in the parallel forms of storytelling predominant among young Thai dissidents today—call-outs of oppression by the Thai state on one hand, and success stories of emigration on the other. The former evidences how life in the kingdom gets crushed by the powers-that-be, while the latter outlines how to escape in search for a better life in a democratic and prosperous country. The two narratives reinforce each other, even if they rarely meet in the same body. And when they do appear in one person’s story, certain parts tend to be omitted in order to satisfy the expected trajectory toward glitz and glamour overseas, as Ratch hints in the case of political asylum seekers who arrived on better shores after the coup in 2014: “Some live glorious lives while completely covering up their wounds underneath their suits.” What is going to be the end result for the world when those deemed successful must downplay their pain or, worse, turn a blind eye to the darkness in the foundations of their beautiful destination country?

It is here that the most important implication of anonymity emerges: the ethical. I’m not referring to a codification of proper professional behavior into a rulebook, but to ethics as a guiding philosophy for a good life. It feels downright unethical to make an illustrious career out of other people’s suffering, when this light is sustained by that darkness. The starker the contrast, the more striking the story. How can a writer who traffics stories between the two worlds—whether in journalism, literature, or scholarship—do so responsibly?

I stumbled upon this thought-provoking passage by Laura Webb: “Is testimonio a genre? Does it matter? For once this question is off the table, we are able to receive testimonio as participants, rather than consumers and analysts, for that is what testimonio requires of us.”

The narrator of In the Land of Madness begins the account as an unemotional reporter who writes for a news-reading public, but, by the end, they become an engaged storyteller who addresses the next generation of fighters in the name of democracy and justice. In the opening anecdote, Ratch describes herself as an unemotional, desensitized reporter in the courtroom—unlike “the friends” who had shed tears. Later in the chapter, she calls herself a “rickety robot” who, unlike a fellow journalist in the office, can comb through the walls of insult from ultraroyalists without being emotionally affected. By the end of the book, however, it is the reporter—rather than the stone-faced mother of an exile gone missing—who cannot hold back their tears. The former journalist’s transformation happens not by design, but by her “prying curiosity,” friendships fallen into the lap which in turn led to personal commitments to political struggle.

Rather than staking one’s authority on a pivotal moment of engendering trust with one’s subjects, Ratch consistently admits to the unbridgeable gaps of communication—faces she cannot read, phrases she cannot understand, tragedies she cannot bear to witness. This suggests that the ethical point of writing and reading testimony is not to necessarily empathize with the pain of others (impossible anyway unless it has happened to you), nor to understand the meanings ‘they’ make out of wounds so that ‘we’ can draw some moral lessons for society (still a one-way street). Rather, what’s crucial is that one must come to recognize oneself as part of the collective endeavor in tearing down the bifurcated structure of the world that continues to wound.

Rather than exhaustively going into literature review like the academic for the purpose of framing one’s arguments, Ratch inserts herself in the field as that connector between the work already done and the work to be done—between struggles past and future. Having shared her knowledge, she disappears into the multitude. Now, it’s up to someone else to carry that knowledge forward through their own action and account as an observer turned participant.

Perhaps this essayist is undergoing a similar arc. Having started from reading too much into the book’s mysteries, I am now more attuned to listening to the stories still left untold. Even if all I do for now is listening and retelling it after the deed is done, who knows what other parts there might be for me—and presumably you, reading this—as the fronds of history unfold?

Peera Songkünnatham is a U.S. resident alien who majored in anthropology in college. They used to be a journalist in northeastern Thailand.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: