In the last act of summer, the Asymptote Book Club is proud to present an award-winning collection of short stories by Danish writer Jonas Eika. In five deeply immersive studies of sensation and cognition, After the Sun is an introduction to a stunning new voice in descriptive prose, establishing a new narrative tradition with non-linear dreamscapes and astounding evocations of the physical body as a site of storytelling. As our own world continues to evolve ever more into the intangible, Eika is a writer that makes corporeal the unreal realities of our times.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

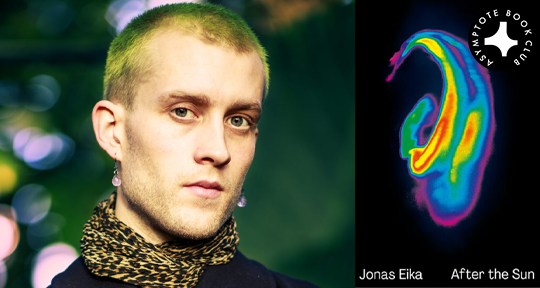

After the Sun by Jonas Eika, translated from the Danish by Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg, Lolli Editions, 2021

To throw things into relief, I’ll play an old trick and say there are two kinds of people—those who seek to understand their dreams, and those who prefer that they remain in the inscrutable realm from where they came. The deciding quality—which also contributes to one’s ability to endure an intensive retelling of another’s dreams—is perhaps having to do with one’s own understandings of a life’s compartments; if within the rationale of time’s chronology, strangeness and encryption can occasionally take on the roles of logic and comprehension. Whether one sees a life’s events as a series of why-questions seeking the compatibility of answers, or if what we perceive as happenings are innocent to their order, oblivious of our insistence on purpose, and the phenomenon of them all fitting into the elapse of a life is simply an incredible feat of human storytelling.

It is incredible: that what baffles us about our own lives—mysteries, coincidences, appearances, and disappearances—is given such distinct clarity when organised into the perpetuity of sentences and pages. They move the world, they provide instruction, they are understood. A gun never appears to not go off. Fiction gives dreams a language that we also speak, ascribing to their impossible nature the subtle conviction of a greater design. In the reassuring procession of language’s patterns, we read life, with all the pieces fit somehow in place.

The stories in Jonas Eika’s collection, After the Sun, move firmly against this reassurance of knowledge; instead they insist forward with all the strangenesses of reality. Time is liquid, settings shift like cards in a deck, the present arrives as if already in memory. The logic of dreams dominate the prose in a determination that thwarts simple comprehension, and as such, Eika has convinced the cacophony and sensory exhilaration of dreams into the accounts of narration. In these five stories, the interruptions of the world—antithetical to our egocentric perceptions of individual purpose—is what drives the reading forward. We are led not by the simple fact of our choices and pathways, but by the world as it happens in experience. Before the discerning objectives of order intervene, we are allowed to luxuriate awhile in the immediate poetry of sensation—consciousness amidst the inexpressible moments of a new encounter.

Eika is especially interested in those dreaming moments where one is estranged from our lives and our bodies. “Alvin,” the story that begins the collection, establishes its opening shot in the aftermath of an “extremely fictional flight.” Then, nothing goes quite according to plan. The bank he’s meant to work at has burned to the ground, his savings and accommodations along with it. Eventually, he falls into the company (and the apartment) of a man he meets on the street. In confrontation with the dissonance between world and interiority, language serves to confirms the singularity of experience; in the wide landscape of world-events, we speak of what is happening to us as a confirmation of being. But where this iteration of feeling and knowing is so often a seeking of solidarity and mutual recognition, these stories instead maintain the volatility of selfhood: life as easily mutated by us as we are by it. The domino-effect of Eika’s narratives then signal a thrilling ceaselessness of possibility, speaking to the world as we know it now, boundless in abstraction. The speed by which we travel, the phantasmagoric architecture of financial markets, the way temporality collapses between reality and virtuality, After the Sun molds these accustomed surrealisms of our everyday into established reality.

Recently, certain emblems of the Internet Novel have made attempts at ascribing our brave new world to literature, yet they remain somewhat unconvincing in their delineation of just how seamless and inextricable our virtual navigations have become with our way of living. Reading about a series of scrolls and clicks feels obtuse, even vulgar. After all, our screens are no longer tools but appendages; writing about them in detail is like writing about the functions of an arm. And language, which we experience only on a plane of linear understanding, does not easily change to adopt new multiplicities. While reading through Eika’s myriad prose, however, it occurred to me that their surreal nature more accurately defines the various spaces our minds occupy—flashing forward and backward, jumping from place to place without transition, all the while carrying the continuity of an uninterrupted experience, ready to be picked up from anywhere, at any time.

The world refracted through these prisms of these stories do not join in any obvious affinity. The streets of Copenhagen, the beach clubs of Mexico, the Nevada desert “ribbed by streams and salt lakes.” But there is an identical nature in how they are navigated and imagined. Eika has a touch for the sinfully visceral language of geographical tension—descriptions that do not create an image, per se, of the place, but a psychology of it:

That day, even the planes were beautiful. Broken air. Plants shooting up through broken asphalt. Rancid smell of beef and other dead animals in a market on the city outskirts. A gorgeous butcher shop, wasps floating in blood.

In dreams, even places you have known all your life disintegrate into fragments of barely-knowing. They pervade with the secret conscience of selfhood, and are so often unreconcilable with one’s actual presence. The arrogance of the dreamer is the rearrangement of worldly matters—a latent power.

This power, if not of divinity, is one of disembodiment. Movement, in dreams, is riskless and transformative. The body takes on impossible tasks. In a total embracing of dreaming’s reality, Eika writes with a maximum impassivity towards physicality. In “Bad Mexican Dog,” a group of beach boys—who complete the greasy resort fantasy with erotically charged services—relinquish themselves to the forces of skin-on-skin with wild abandon. In describing an encounter with an American tourist, the narrating beach boy reports:

. . . his excited voice makes me rub the sunscreen in way too fast, which gives him that piece-of-meat feeling, and they don’t like that, so I get a bad tip.

Yet, later, when he meets with a partner to enact a more consensual sexual choreography, the language turns liquid, osmotic. Their bodies infuse one another and mutate, becoming texture, colour, movement itself. “The sun is inside me now because the sun sets in the ocean.” Sex, as it is written, does not seem like an act of passion or desire so much as it is a mergence, and almost indiscernible from descriptions of violence. Blood, in the duration of an assault, is a “long red squirt turns orange in the sun lands on white sand.” An orgasm is “a squirt of thick white juice that comes to life in the water.” The fluid potentialities of the body are freed in their living potentials, as if it is the ink by which human acts are inscribed upon the world.

In each of the stories in After the Sun, the characters come up to one another as if trying to interpret how they are sharing the same, temporary reality. They grow to include the gradual familiarising of a stranger’s presence, an unspoken negotiation of opposing roles, a wary curiosity as to the different paths taken to arrive at the same place. With common patterns of acquaintance foregone, what results is a depiction of the other as an addition of one’s unspoken feelings and thoughts. When the narrator of “Alvin” shares a bed with the titular character, he describes it as a psychic intimacy instead of a physical one:

Our awareness filled the room like something large and encompassing, and if I was inside it, then Alvin was too.

Much of the adeptness of the prose in this collection can be attributed to the poetic and musical instincts of translator Sherilyn Nicolette Hellberg. In an interview with the New Yorker, Eika states: “I always try to work a subtle strangeness, or even ineptitude, into my writing, even when it’s quite literary, and Sherilyn picked up on that.” There are occasional instances of awkwardness—repetitions and adjectival interjections are frequent—yet the rhythmic build of the writing introduces them like a fantastic oratory. In “Rachel, Nevada,” a call to extraterrestrials is described: “It was more like someone or something was stimulating his throat into speaking, and as a side effect, was activating the memory of a distant, desert life.” This sense of evocation moves across all of Eika’s narrators, who do not tell their stories for the sake of having them heard, but because they initiate into a greater, more universal effect of alienation, the intimacy of sharing strangeness, and the sensation of being carried by the world.

But now I know that you should always trust your intuition, even when it’s made of fear, because otherwise you might end up getting into a car headed somewhere strange. And even though you can’t keep up — maybe you’re still standing on the sidewalk — your body is in the car, and then afterward, every time you’re reminded of what happened, it feels like somebody else’s bad feelings, but you’re the one who has to feel them, you can never leave your body all the way.

I’m sure there are people reading this for whom the sentence: “I had the craziest dream last night,” is an immediate signal to exit the conversation—I’m the same, but where dreams are a tiresome litany or inexplicable objects for some, under the capacity of a capable storyteller, they become a study of life at its most furtive and incommunicable. It is why dreams continue to fascinate and irritate in equal measure—that they are at once question and answer, interchangeable.

In speaking of the Belgian poet Henri Michaux’s mescaline-infused writings, Octavio Paz wrote: “The poet saw his inner space in outer space. The shift from the inside to the outside—an outside that is interiority itself, the heart of reality.” The work of Jonas Elias follows this same lineage of illuminating sensation. The perplexing nature of these stories is undeniable, but the writing is trustworthy enough that one can allow the fiction to carry us. After all, nothing is as strange as life sometimes is, and that carries us through all the time.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. Find her at shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: