Keila Vall de la Ville’s The Animal Days explores young adulthood at high altitude. The narrator pursues a passion for rock climbing as she struggles to navigate a similarly perilous life at home. But the world of climbing and her escape from civilization come with their own dangers, which close in as the narrative hurtles toward a suspenseful finale.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

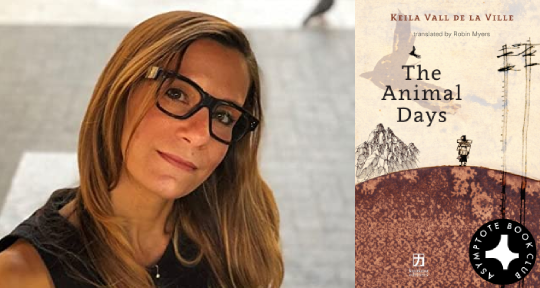

The Animal Days by Keila Vall de la Ville, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Katakana Editores, 2021

Rock climbing invites glib metaphors. Inspirational posters—prolific in offices where the only vertical challenge is conquered at the touch of an elevator button—often use summits to symbolize widely held values like perseverance and determination, but the experience of serious climbers is anything but universal. Their insular world trades on levels of pain, risk, and anticipation foreign to the average individual. Enough time in that world can warp perceptions of the other world—the one where the rest of us live. “Thanks to the mountain, you’re able to make out the mechanisms that dictate daily life, life on land. You come back different,” explains Julia, the young narrator of The Animal Days. “Now that your battery has been recharged, now that you’ve obtained this ultraviolet vision, you carry on until you need to plug back into the mountain again. Until everything starts to lose its luster.”

The Animal Days, Keila Vall de la Ville’s third work of fiction and the first to be translated into English, invites readers into the climber’s rootless milieu. Julia’s journey is a world tour of precipices, as she balances her obligations to her dying mother against an escapism inherited from her absent father. Estranged from her everyday surroundings, she finds intimacy among her climbing friends, who provide a respite from her internalized abandonment, and who alone can understand the peaks and falls of a life on ropes. They shirk steady jobs and spend their time chasing both chemical and literal highs.

Her mother, however, can’t fathom her daughter’s aversion to setting up a legitimate life, a life she can recognize. “We’re not animals,” she says from her hospital bed. Without a plan, she warns, Julia will get left behind, “suspended in midair . . . with no wings and no safety net.” But while Julia’s ultraviolet vision unlocks certain powers of close observation (“You stay there, staring at a pebble, a beetle, a frosty glimmer on the ground, and you want to live inside that beauty”), it also blinds her. “Everything is now,” Julia says, like a wolf bent on survival.

One of Julia’s climbing partners, Rafael, embodies that primal existence; he scrapes up enough money to buy gear and plane tickets but scavenges food from the garbage, choosing carefully from the buffet of dumpsters behind restaurants. Prone to aggressive drinking and partying, he doesn’t let up until he sees blood, but Julia comes to recognize her own reckless zeal in him. “You can’t see it yet, but we’re the same, you and me,” he tells her soon after they meet. They embark on a tumultuous, abusive relationship, bound together by climbing, sex, and Rafael’s laconic postcards, scrawled in childish handwriting.

Vall de la Ville’s previous work, including the short story collection Ana no duerme y otros cuentos, evinces a preoccupation with memory. The Animal Days is structured as a reflection on a short period in Julia’s life, and as with memory, the narrative is often disorienting, jumping back and forth in time and across three continents. Julia’s conversations with Rafael merge into conversations with her mother, and their emotional holds on her grapple for primacy. Memory, too, implies a subconscious analysis—“You keep living, you keep getting to know yourself”—and she turns to the language and lessons of her climbs to excavate past trauma.

“It’s one thing to climb,” she relates. “It’s another to choose walls that will destroy you unless you make it to the top.” Self-destruction beckons, both on the wall and in the sleeping bags she shares with Rafael. She exposes her deepest vulnerabilities to him. When they scale rock faces together, she gives him the power to end her life; when they share their rawest selves in a wilderness few can access, she hands him the power to wreck her from the inside out. “You’re mere millimeters from the edge, with a body on top of you that could erase you entirely.” When he takes advantage of that power, the generic climber’s determination takes on a sinister cast in Julia, who returns to Rafael again and again—another peak to conquer.

Robin Myers, an award-winning poet and translator based in Mexico City, lends a wide-ranging language to this novel, whose settings span from Peru and Vall de la Ville’s native Venezuela to California and Kathmandu. (Vall de la Ville is now based in New York City.) The various locales, filtered through Julia’s memory, exist primarily as backdrops for her emotional journey. The itinerant narrative is representative of a millennial, vagabond worldliness, somewhere between tourism and travel. The novel’s sequence of events is propelled by movement but remains independent of place; Julia connects with a Spaniard in Nepal, a Chilean in California, and a German in India.

Climbing—with its particular culture and vocabulary—transcends borders, and this fast-paced novel is situated in the immersive world of the sport more so than in any place that shows up on a map. Myers’s translation expertly guides readers through the dense cartography of emotional and physical territory that Vall de la Ville charts in Spanish. The author has been a climber for twenty-five years—she placed at the 1996 Pan-American Climbing Championship—so Julia’s narration is naturally rife with specialized terminology (her cat, Grigrí, for example, is named for a belay device). The lingo doesn’t impede the plot but serves instead as a foreignization technique, further distinguishing Julia’s environs from the workaday world she so disdains.

The word “tightrope” appears frequently throughout the novel, in both literal and figurative contexts. (In addition to rock climbing, Julia and her friends experiment with parachuting and slacklining.) The Animal Days recounts a time in life, young adulthood, that permits the reckless, primal focus on the now that animates Julia and her friends—a line pulled taut between the innocence of childhood and the responsibility of adulthood. Consequences seem impossibly distant.

Vall de la Ville resists the easy corniness of motivational posters and instead complicates simple comparisons. Like many high-stakes sports, abusive partners create an insular existence that’s difficult—if not impossible—to leave behind. They, too, deal in danger and anticipation. The Animal Days achieves a breathless momentum as it gains altitude. Those impossible consequences close in, death comes startlingly close, and Rafael’s abuse takes an ever-growing toll. The further Julia climbs in her pursuit of Rafael, the further she has to fall. Will she make it to the top—or will the route destroy her?

Allison Braden is an assistant blog editor for Asymptote and a contributing editor for Charlotte magazine. Her journalism and translation have appeared in The Massachusetts Review, Columbia Journalism Review, Outside, and The Daily Beast, among others. She’s seeking publication for her translation of Arelis Uribe’s award-winning collection of short stories, Quiltras.

*****

Catch up on the latest Asymptote Book Club picks: