The persuasive potentials of storytelling don’t always hold the life-or-death thrill that they did for the mythical Scheherazade, who spun her narratives to stay alive, but as the profundities of Magda Cârneci’s FEM prove, there is always an enchantment in speaking one’s own experiences to another. Exalted with Cârneci’s celebrated poetics and visceral in its discernment of gendered bodies, our Book Club selection for June is a novel that speaks to our evolving understandings of physicality, sexuality, and selfhood as refracted in societal prisms of sex, femininity, and myth.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive Book Club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom Q&As with the author or the translator of each title!

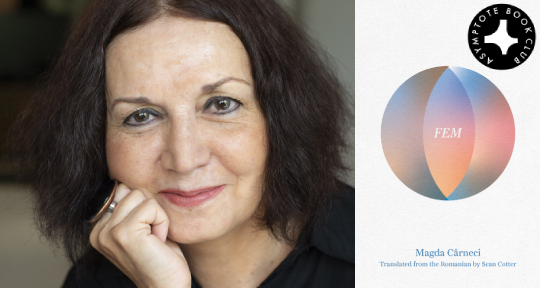

FEM by Magda Cârneci, translated from the Romanian by Sean Cotter, Deep Vellum, 2021

In the very first lines of FEM, the protagonist—a fictionalized version of author Magda Cârneci—compares herself to the mythical heroine Scheherazade, then immediately troubles the comparison: “A little, everyday Scheherazade in an ordinary neighborhood, in a provincial city; your personal Scheherazade, even if you won’t cut my head off in the morning, when I fail to keep you awake all night with extraordinary stories.”

How, then, is she like Scheherazade? She will indeed attempt to enchant her listener, a lover, with a string of stories—but are all women who tell stories like Scheherazade? It is not a simple affinity between the two women that gives meaning to the comparison, but, more fruitfully, the symmetry’s imprecision. Like the north ends of two magnets, the two storytellers’ refusal to meet tantalizes, inviting the reader into the no-man’s land, in which they may question—or even participate in this exchange of identities. Cârneci’s own active approach to living in a body, in fact, is exactly what she begs her listener/reader to adopt, and her appeal is so breathtaking, it’s a wonder anyone could refuse:

We are seeds sown into the brown-black loam of a terrestrial existence, and we must germinate and rise slowly from our fragile burgeoning, our green sprouting, through layers of clay and stone, through bacteria, worms, and insects that wish to devour us, we must pierce through sheets of underground water and enemy root systems, our germinations are deviated by contrary forces, deceived by gravitations and visions, by temptations and traps, but pulled upward by an atavistic, core instinct, along a fragile thread of light, pulled by an inverted, celestial gravity, we are tractable, attracted toward growth at any price . . .

Like One Thousand and One Nights, FEM alternates between the narrator’s real-time direct address to her lover—indicated by italics—and the stories that she tells him, admittedly more biographical and weaker in narrative than those of her predecessor. She relates anecdotes from her life, but they aren’t filled with drama and adventure—at least not in terms of their action. Instead, they are of moments—however superficially mundane—when she accessed a sort of transcendence. She often recognizes the onset of this state by a physical sensation:

And out of the blue, I was struck, physically, on the back of my head by the simple idea . . . that I was still missing something important . . . When I face this—how to put it—portal between the world and the mind that secretes a kind of tridimensional metaphor, we could say, because it is invisible and veiled, and it unfolds in space and time, and inside of which I live my life, I am always blind, always ignorant of the deeper meanings of these almost banal events, I always sleep through their simple and mysterious messages.

Though the state is fleeting, she celebrates, prolongs, and practices it with her writing.

The listener—the lover—is a schlub. I don’t know if there’s a word for that in Cârneci’s native Romanian. He drinks, cheats, and tunes the world out with bad TV. But she does love him, and though she’s not in danger of decapitation, she is in danger of being left. Here we find a point of comparison with Scheherazade. Cârneci’s storytelling hopes to change the apparent inevitability that a man will harm a woman with his narcissism and carelessness. “You are as empty as a crumpled paper bag, as a broken vial, you are disgusted that you have fallen into the carnal trap again, you are sick that you let your fecund liquor escape your body again, your precious, sacred, virile fire. But what do you know about me, about the soft, disheveled duvet under which you lost yourself for a second . . .” By way of loving him, she hopes he will be able to “access something, something essential within you—as bored, as tired, as sound asleep as you are, something that will keep you awake the rest of your life. I will be a kind of Scheherazade.” She adores experimenting with her capacity to love. Whether or not Scheherazade spoke from the same intention is a matter of speculation, as is that of Cârneci’s success.

Crucially, her forgiving nature extends not just to men, but to herself as well, and to all of humanity. With her memories, she reveals her equanimity; neither the pain nor the ugliness of material existence deters her fascination, and its sweetness does not distract her from the higher planes to which she aspires. As a little girl, she nearly drowns her baby sister in a basin of water, and as she replays the memory of this childish hatred, she dwells thoughtfully on the beauty of nature, the thrill of early independence, and the painful love of her adult relatives—without imposing value judgments. Years later, after an earthquake acquaints her for the first time with the fear of death, she loses her virginity to a man who loves her, but towards whom she feels no attraction. Afterwards, she is unsettled: “And all I could put together was that I was foreign to myself, and that I did not know me or love me, that I was far from my real self.” Rather than tuning out from this alienating encounter, as so many would, she continues the search for whatever it is she didn’t find in his bed, playing both the male and female roles and marking her impressions of death and estrangement in her self-initiation to sexual pleasure. “Because this carnivorous world, this crude and loving universe extracts its ecstasies through its own fastidious destruction. And through ecstasy it recompenses its victims as it completes its disasters. And through ecstasy something comes, a unifying vibration, a mental geyser, a bridge to the other world.” Just as all beings for her inspire feelings of love and interconnectedness, all experiences contain the seed of transcendence.

The natural world, for Cârneci, is extremely fertile ground for transcendent experience. Images of nature are often either exotic, overwhelming, or both. It is distant from her urban life, unknowable and uncontrollable. At the same time, she imbues images of the natural world with erotic language, manifesting its intimacy. She describes the ocean, for example: “the waves continued to land with their massive, enormous sound, the pure, fecund saliva of a gigantic liquid mammal. What smelled so strange, so sharp and aggravating, so wet and encompassing? What was that smell? A woman. A vast, all-encompassing woman.” As usual, the contradiction between duality and oneness stimulates her.

Immersed in FEM‘s stunning prose, we can imagine translator Sean Cotter as a surfer, abandoning himself to the unearthly force of Cârneci’s poetic sensibility; the lucky spectator on the beach witnesses their dance as if by fortune. Luxuriously long sentences sweep us along, entranced. The word choice and imagery startle and delight. Take, for example, Cârneci’s early childhood impressions of her mother: “Oh, mother, bittersweet honey, enormous female, all-encompassing, in whom I am lost, drowned, like a poppyseed in a cloud of cotton candy. Suffocating, sticky candy cloud, where I want to dissolve, happily, to lie buried under layers of soft fog and ancient fat.”

It is entirely consistent with the worldview that the book proposes that its translator is male, though the content is rooted decidedly in the experience of living in a female body. We all contain, consume, and emit the other, with union as the ultimate objective: “I want to annihilate you, to destroy you, to be you, for us to be one. You want to annihilate me, to destroy me, to be me.” The collaboration also speaks to the recent discourse about identity in translation. It’s up to the reader to decide what it says, but based on the ethos of the novel, it would be fair to assert that there is inherent value in naked encounter with the other.

Though Cârneci’s compositions fail to win back her lover, they accomplish their other implicit goals. Their beauty mesmerizes; they inspire engagement, reflection, and questioning; and they make a passionate case against passive consumption—both of art and of life. This problematic reincarnation of Scheherazade carries her dangerous torch with honor.

Lindsay Semel is an Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Catch up on previous book club picks on the Asymptote blog: