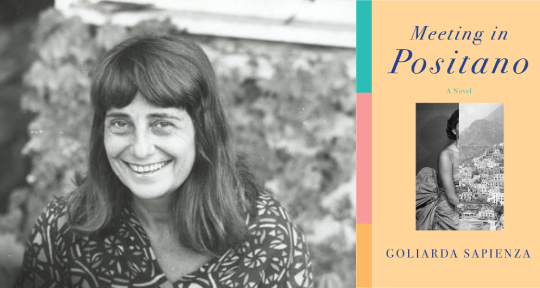

Meeting in Positano by Goliarda Sapienza, translated from the Italian by Brian Robert Moore, Other Press, 2021

Meeting in Positano was the very last novel that Goliarda Sapienza wrote before she fell to her death in 1996 at her home in Gaeta. Frustrated by many failed attempts to publish her writing throughout her life, Sapienza’s ultimate book was fraught with the existentialist neuroses of modernism as she searched for ways through and out of its sprawling, vicious embrace. Between its fragile subjectivity and ambivalent subject, Meeting in Positano traces the psychology of its protagonist, caught between film production in the Italian capital and the pacifying lure of the titular out-of-the-way town—wherein a fading daughter of the old aristocracy has also come to shed her qualms with the pace, pressure, and emptiness of materialism, money, and men.

The daughter of Sicilian socialists—who, among many plaudits, published Antonio Gramsci—Sapienza lived along that drift in which sensitive artists become hardened intellectuals before succumbing to outright revolution. Despite the environment of ardent intellectualism, the wayward, postwar Sapienza children were afloat in an Italy which resembled a rudderless raft in the Mediterranean—a country that had gone slack in its attempted confrontation of the country’s unresolved tendencies to fascism. In its quest for spiritual emigration, the literary work of Goliarda Sapienza details the inner lives of her fellow Italians, challenged by the trials of collective renewal following years of unspeakable despair during and after the years of World War II—even if the traces of those years are only seen, or merely felt, after the fact.

Meeting in Positano, translated by Brian Robert Moore, continues this thematic exploration, as the traumas of wartime violence appear in hints and traces amidst this tale of friendship in the bucolic coastal village of Positano—a surprising haunt of rare peace in central Italy. The novel, almost plotless and buttressed with chapter-long spats of dialogue, spotlights three sisters, most notably the eponymous narrator Goliarda—a particularly perspicacious young woman whose eye catches an enigmatic traveler, Erica. Their distant affair—a flirtatious asexual intrigue—evokes an emotional release, which the narrator finds in fleeting moments over the course of many years as the sisters continuously return to Positano. However, the iron hand of grief is never far and afflicts the novel’s characters with sudden, intimate tragedy.

With lucid prose that is at once descriptive and meditative, threaded with pearls of phrasing that provoke the mysticism of conceptual thought, Meeting in Positano is a distinctive contribution to Italian literature, crafted from Sapienza’s richly informed, semi-autobiographical stance as a metropolitan woman with both countrified origins and ideals inherited from Italy’s educated class. In addition to building on the foundations of her background, the book also exhibits her filmic ear for dialogue and cinematographic imagination for scenography, a mix of flamboyant intellectuality and streetwise determination drawn liberally from her stellar assortment of connections to the film industry, which had become one of Italy’s primary mediums of cultural expression. Throughout her life, Sapienza fielded the attention she earned from early successes on the stage and screen, and Meeting in Positano airs her grievances with that most demanding sector—its assumption of the worldly values that the narrating Goliarda finds sanctuary from in the slow passage of time, the eternal cyclicality of life, in Positano. Through her narrator, Sapienza gives vent to a desperate fervency, her voice exuding a powder keg of suppressed passion, personified in the unrequited affection that Erica lured out of Goliarda. The unobtrusive complexity and dramatic tension builds on the sands of an unsettling psychological landscape, and her characters have a Chekhovian taste for dense and extended dialogue, braving the storms of late-twentieth-century reconciliation along the tides of progression, caught between the global capitalist march towards infinite growth and more reflective, inclusive postmodern sensibilities.

Named with characteristic darkness, Positano is “love’s tomb,” a witticism attributed to a painter called Lorenzo, whose membership among the culturati of creatives, intellectuals, and lovers smacks of Sapienza’s authentic, world-weary experiences of going back and forth from the cities of Rome and Milan to Italy’s beachfront countrysides. Yet, it is concurrently a bold, pointed expression, considering the fate of Erica, who exclaims that Positano has cured her after a soured romance ended somewhere between business and pleasure. Raised on old money, Erica would seem to contrast with Goliarda, whose quixotic leftism is autobiographical. Instead, Goliarda’s empathy is boundless as she listens to the visitor opining on everything from her dashed hopes to art theory. Although Erica displays a bend toward fascist anti-modernism—decrying the dreamless, cold mechanics of photography—Goliarda ultimately claims that her only fault was that she treated small and important matters with the same gravity.

Toward the end of the novel, during an especially verbose meeting, Erica digresses for many pages in her direct address of Goliarda, which seemingly has become a thinly veiled exercise in the author speaking to herself. Erica appears impatient, overwhelmed, and unwilling to impart her wisdom, but does so with signature Mediterranean relish: “And besides, life is always a novel left unwritten if we leave it buried inside of us, and I believe in literature.” Moore, who received the 2021 PEN Grant for the English Translation of Italian Literature, has delivered a fresh, airy cleanness to Sapienza’s writing, though it appears that the lilting gravity and rich flavors— normally prevalent with Sapienza’s knack for vernacular Italian speech—is replaced by the comparatively stultified manner of the English. As part of the novel’s long, slowly unwinding conclusion, Goliarda bemoans: “My father used to say that when times change—he was referring to the end of the First World War—not only does our way of speaking change, too, but so do sensations, feelings, et cetera.”

Meeting in Positano is easy to read, but it is not an easy read. For all of its homing-in on the microcosmic proportions of human drama in quaint Positano, the novel is best read with a literacy in the breadth of Italian geography, and a grasp of how the political and class hierarchies of postwar Italian culture confronts the borderless, assimilative Western urbanization of the globe. Along with quick references to Homer, Tolstoy, and Nietzsche—which pass through the narrative prose with the quick-wittedness of a proudly erudite European—the prose also nods at Italian aesthetes less known to the outside world, including the genre bestseller Luciana Peverelli or the popular librettist Giuseppe Giacosa.

Italian identity is, in Meeting in Positano, exacted from a self-criticism that might also befit the overeducated, default existentialism of the global, Americanized middle class. It is a condition of excess, decadence, and finally, nomadism. Since she was a child, Erica sang, danced, played any sport, copied any painting, but never landed square on one thing; she confesses to Goliarda that she had failed even at becoming a murderer. The degree to which she opens up is a preface for a breakdown, conceivably mirroring Sapienza’s prolific literary productions, which, within her lifetime, had returned—like Positano itself—to the unknown.

Angelo Pellegrino, Sapienza’s spouse, reflected on Meeting in Positano in an afterword, entitled “Places, Characters, Happiness,” the piece is his emotional recounting of what Sapienza’s last novel meant to those closest to her. Sapienza had first gone to Positano for a film production. That sea—along the Amalfi Coast and mined for years after World War II—opened up in the 1950s, and its fecund silt was where Sapienza found her muse. A Sicilian, the sea was her life, and her return to its shores buoyed her out of suicide, even as she wrote of the tragedy she found in its waves, which attracted her until Positano itself died—or ended its own life—and changed indistinguishably from its past.

The specter of suicide looms in Meeting in Positano as it did in Sapienza’s life; following her first suicide attempt in the spring of 1962, Sapienza’s bookish intellect survived shock treatments at a psychiatric asylum. She went on to embark on a series of autobiographical writings, which carried her through the next five years. Although the literary establishment roundly rejected her novels and texts during her lifetime, Penguin Classics published the English edition of her magnum opus, The Art of Joy, in 2013, after Einaudi—a prestigious publisher in Italy—announced that it would edit and release all of Sapienza’s precious writings.

This second appearance of Sapienza in English comes after the Ferrante novels enlightened the world to the spirit of contemporary Italian fiction by women. But whereas the early twentieth-century roar of such internationalist luminaries as photographer Tina Modotti immortalized the progressive Italian woman as canonical to Western cultural history, Sapienza’s struggles—to touch the heart of her country, to venture into its unsung towns, and to reach out as a woman to love, even platonically, another woman—showed a penchant for modernist interiority in a literature that did not quite possess the same vogue appeal.

It is possible to feel, after rereading Meeting in Positano, that Sapienza identified with that town on the Amalfi Coast, with its Saracen gaze focusing far out to sea. She was married to its infinite waves, sharing her afterlife with its shores, which had once rocked with the rumble of exploding mines. Displaced from her Sicilian birthplace, the stage and screen business of big Italian cities, and the rush of machine-addled moderns to her beloved Positano, Goliarda Sapienza has finally become, posthumously, the widely published and translated author she never had the chance to be in life. Meeting in Positano delivers an unfaded love letter to friendship in the face of mortality, in the process revealing just who one midcentury, female Italian author was, when she felt most like herself.

Matt A. Hanson is a freelance journalist and art writer based in Istanbul, where he contributes to Artnet News, Tablet Magazine, The Millions, Words Without Borders, Al-Monitor, forthcoming for the Jewish Review of Books, and many others. He is an editor of artist books and exhibition texts for Arter, Dirimart, Pera Museum, Koç University Press, Yapı Kredi Publications, with collaborations featuring the poet Lale Müldür and the artist and writer Deniz Gül. For a series on art writing in Turkey by SAHA Association, he wrote an autobiographical essay.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: