With an infectious blend of humor, satire, and biting social commentary, Yassin Adnan’s novel Hot Maroc gives readers a portrait of contemporary Morocco—and the city of Marrakech—told through the eyes of the hapless Rahhal Laâouina, a.k.a. the Squirrel. Painfully shy, not that bright, and not all that popular, Rahhal somehow imagines himself a hero. With a useless degree in ancient Arabic poetry, he finds his calling in the online world, where he discovers email, YouTube, Facebook, and the news site Hot Maroc. Enamored of the internet and the thrill of anonymity it allows, Rahhal opens the Atlas Cubs Cybercafe, where patrons mingle virtually with politicians, journalists, hackers, and trolls. However, Rahhal soon finds himself mired in the dark side of the online world—one of corruption, scandal, and deception. Longlisted for the International Prize for Arabic Fiction in 2017, Hot Maroc is a vital portrait of the challenges Moroccans, young and old, face today. Where press freedoms are tightly controlled by government authorities, where the police spy on, intimidate, and detain citizens with impunity, and where adherence to traditional cultural icons both anchors and stifles creative production, the online world provides an alternative for the young and voiceless. We are thrilled to partner with Syracuse University Press to present an excerpt of its debut in English.

The Atlas Cubs Cybercafe

The autumn winds blow over Marrakech’s gardens, parks, and trees as September draws to an end. The entrance exam period has passed and those of Rahhal’s and Hassaniya’s friends who passed the exams have enrolled in training schools for primary and secondary school teachers, while those who flunked have gone back to throw themselves into the embrace of a deadly emptiness. Students went on with their university lives, embarking upon another semester of lectures, discussion circles, and endless cafeteria fights, whereas those who failed were deprived even of the routine of attending classes. Hung out to dry like clothes on the line, blowing in the wind, a sense of worthlessness gnawing away at them. As for Rahhal, he found himself face-to-face with what Hassaniya had suggested. He had no other option. And he couldn’t have hoped for a better solution himself.

He stood ill at ease and submissive at the door of the principal’s office, and after Hassaniya asked if he could enter, Emad Qatifa himself rushed forward to welcome him.

“Please . . . please . . . Mr. . . . Mr. . . . Rahhal, right?”

“. . .”

“Please, come in.”

In a show of gratitude, Rahhal just nodded. He was nervous and flustered, unable to raise his eyes up to those of Emad, who seemed nice, while Hiyam, the actual principal of the school, remained sitting at her desk. She was totally indifferent. She didn’t stir in her chair at all. She was silently watching the scene with an expression that moved between severity and detachment.

The meeting ended quickly, quicker than Rahhal expected, and without him having said a single word. He found himself in the courtyard of the house that had been turned into a school, having gotten the job right then and there, but not yet understanding exactly what his job was, or what exactly the position entailed. The school had a teaching staff whose names, along with the details of the subjects they taught, were posted on an educational chart hanging to the right of the principal’s office, and Rahhal’s picture was not among them. The school had a doorman, who stood at the gate washing Hiyam’s car, watching over Hassaniya’s motorbike and the teachers’ bicycles, and selling single cigarettes to passers-by, so even this position was not available. What was left, then? It was clear that Rahhal would remain leaning up in the corner of the courtyard like a bench player on a soccer team. He would remain until things became clear. Watching the students come and go, making himself available to everyone: Emad Qatifa, the owner of the whole thing; his wife, Hiyam, the principal of the school; and her vice principal and private secretary, Hassaniya Bin Mymoune.

***

When Emad Qatifa agreed to Hassaniya’s suggestion of employing her husband along with her at the Atlas Cubs Private Elementary School, all he wanted was a guarantee that she’d take the job. There was a consensus inside the family council, headed personally by Qatifa, Sr., that their neighbor’s only daughter was qualified for this task because of her high moral fiber and university education, and that she was also more capable than a stranger to deal with Hiyam’s mood swings. The condition that Hassaniya adroitly brought to the table in the form of a suggestion resulted in his de facto hiring, pending further clarification as to what he would do in the future. Thus, Rahhal received this opportunity without Emad or Hiyam having to worry themselves about the exact nature of his job. He found himself as an employee with no defined tasks. Besides his daily job driving the motorbike the school had given to Hassaniya, and outside of taking Hiyam’s orders to the neighboring café and bringing back lunch sandwiches for himself and Hassaniya from the restaurants on Dakhla Avenue in Massira, Rahhal didn’t really do anything of note. He would watch the students come and go, monitor this or that classroom whenever the instructor would go to the bathroom or head to the principal’s office, and would waste the large part of his remaining time yawning in the school courtyard, lazy and resigned.

Hassaniya’s boldness with Rahhal and the sharpness with which she occasionally addressed him emboldened Hiyam to do so as well, and then some. But as soon as she discovered that the man was not looking for respect, nor was he concerned with issues of dignity, she left him alone. For Hiyam absolutely loved petty disputes and stubbornly engaging in little skirmishes, and she had raised the fabrication of problems and picking fights to an art form. But Rahhal was boring and weak. He wasn’t the type who could keep up with her in that domain. And because Hiyam was a gracious winner, she despised him to her very core, not even giving him the time of day.

When Hassaniya spoke to her about his typing skills on the computer, Hiyam casually suggested that her husband open the building’s locked garage for Rahhal, buy a computer and photocopying machine, and put them at his disposal. That’s how he took on writing and copying all of the reports and private administrative documents for the school, as well as the teachers’ documents and departmental exams, as long as the shop remained open to all. This would provide publicity for the shop and the school. With this arrangement, they found a real job for Rahhal to justify the salary he had been receiving for the past four months.

Emad, who welcomed the suggestion, also thought of negotiating a contract with Maroc Telecom that would allow him to open a téléboutique in the spacious garage. Thus, Rahhal found himself in front of a computer and a photocopying machine with three telephones attached to the left-hand wall of the shop, open to the public.

***

Minding the telephones won’t require too much of you, Rahhal, besides exchanging the customers’ bills for dirham coins, then emptying the bellies of these phones of the coins they held at the end of the day. Other than that, you’ll have all the time you need to listen in on the lives of others from behind your rickety, wooden desk. “Hello, Naima?” “Hello, Hajj?” “Hello Hajja?” “Hello, my beautiful.” “Hello, my love.” “Hello.” “Hello.” “You’re hanging up on me, you whore?” “You remember what you did!” Endless conversations. Provide change to the customers and enjoy yourself listening in on their conversations, on their lives. Photocopying is a mechanical procedure no less mindless than watching over this or that classroom while waiting for a teacher to come back from the bathroom. As for using the computer, typing on it and caressing the keyboard, there’s no pleasure like it: clicking the t with your index finger, the ring finger caressing the m, the middle finger pressing firmly on the n, a light push on the b, then running the pinky finger softly over the belly of the emphatic t. His fingers dancing and flying across the keyboard, Rahhal follows what they do with his eyes fixed on the screen. He is filled with a strange feeling of pride comparable only to the feeling he got when he learned to drive his Uncle Ayad’s motorbike as soon as they moved in to live with him in his house in Moukef. But driving here is more enjoyable, and safer. Driving on a clear, white, well-lit stretch. No jammed streets or bikes running red lights. No buses polluting the air with their heavy black smoke or the roar of their engines. No pedestrians walking outside of the crosswalks. No honking car horns. Safe driving on a highway of light.

“Photocopy, please.”

Sluggishly, Rahhal would get up. He’d turn on the photocopy machine. Irritated, he’d take the document. He waits a bit for the machine to warm up. Then: zzzzzz. He completes the task then returns to the keyboard. But gradually he began to steal glances at the documents. He’d look them over a bit as a way to kill time while he waited for the machine to get going. But with time, he would find that there was some enjoyment in making copies. This encounter with strangers, peeking into their lives through the documents they would give to him was not devoid of pleasure, really. The task wasn’t as boring as he had first imagined it.

But let’s set all of this aside.

Let’s go back to our winged horse of light.

Rahhal’s fingers became increasingly light and delicate during their flights over the keyboard. How happy he was with his machine! He began to soar higher and higher, day after day. He finally found the letter dhal hidden among the numbers and figured out how to extract the shadda sign from its hiding place after his search for it over the last few days had completely exhausted him. The exclamation mark was still seemingly impossible, but he would not rest until he dragged it out of its hiding place, too. He would use the shift key and move all around the keyboard until he found it . . . Finally. Eureka! Eureka! He had accidentally pressed on the number 1 and the shift key at the same time and there was the exclamation point, appearing before him slender and tall, standing there self-confidently on top of its small, solid base raising its eyebrows and sticking its tongue out at him.

Way to go, Rahhal . . .

Drag the mouse by its light tail and continue your magnificent wanderings in and out of words and sentences. Align the paragraphs well. Type the title in large, prominent letters. Change the background color. Get rid of the extra spaces. Line up the margins and the blank spaces of the paragraphs. Use the spell-check while you type . . .

“One photocopy please, my friend.”

“Huh?”

“A photocopy of the card, if you wouldn’t mind?”

She was tall and beautiful. Wearing a turquoise djellaba à la mode with macramé and silk threads. Her hair was jet-black. Her eyes were dark. And her face was sad.

Name: Nafissa Gitout

Birthdate: 3/14/1971

Profession: None

Address: Douar Aït Mohammed, Commune (. . .) District of Sefrou

This card is valid from 8/13/1989 to 8/12/1999

But what are you doing in Marrakech, Nafissa? Why did you come from Sefrou, the land of cedar and cherry trees? The land of cherries, the Cherry Festival, and the Beauty Queen of the Cherries Pageant? What is it that brought you here, you with the sad eyes? Work? What work, while you’ve listed “none” as your profession? What work, Nafissa? What’s a beautiful girl like you doing in a city more than 400 km from her hometown?

Rahhal was sure to survey the documents that were handed to him with piercing eyes before copying them. But some important information escaped his memory.

For example, Nafissa, the name of the hamlet and the region are included, but the commune is missing. Was she from an urban or rural commune? From Sefrou, the city, or from Bhalil? From Hermoumou or Bir Tam Tam? He no longer remembers. That’s why he made sure not to be so careless with such things in the future. Next time, he’d be sure to make an extra copy for himself—secretly, of course—which he would examine carefully and at his leisure after the customer has left.

Thus, a fabulous archive began to gather in the front of Rahhal’s desk: identification cards, passports, residency certificates, marriage contracts, birth certificates and others for death, proxies for buying and others for selling, work certificates, small paper slips from teachers, educational inspectors’ reports, exams from the instructors of the Atlas Cubs and the surrounding schools.

Rahhal would enjoy reading those documents, deconstructing their components and thinking deeply about what they contained. And the documents that interested him or excited him, or that made him feel at ease, those he would choose to practice on the computer. He’d place them to his left and move the mouse with his right hand. He’d open a new page in Word and start typing.

***

The king is dead, long live the king!

Rahhal, like most people in the country, sensed the difference. People were breathing a new air in the street and on the bus, at home and around the neighborhood, in the markets and cafés, everywhere. True, the regime was one and the same, and even though the previous opposition government came to power in 1998, a year before Hassan II’s death, it had been running the country’s affairs with his full approval. “Change from inside the system, with continuity.” This was the slogan of the time. The papers were talking about fierce opposition to the reformist initiatives launched by the new ministers on the part of the shadow government, and there were pockets of resistance to change. However, although the pace was somewhat slow, change was possible, and those dreaming of it were growing in number.

Hassan II died on a scorching hot Friday in July 1999. Moroccan television began to broadcast Qur’anic verses and at first, Moroccans wondered why such a sudden righteousness and piety had struck the television broadcasters and programmers. The door was opened to many different interpretations, and rumors ran rampant. Agence France-Presse spoke of the king’s probable death, according to sources close to the palace. But details remained blocked in France, while the people here remained in suspense until the Spanish press released a statement announcing the death of the Moroccan ruler.

The king is dead. But kings don’t stay dead for more than a couple of hours. After that, they enter the history books and ascend to the level of myths. A king’s death doesn’t last more than a few hours. The king is dead, long live the king! That same day, loyalty was professed to the crown prince Mohammed, son of Hassan, in the throne room of the Royal Palace in Rabat. And the Government of Change, run by a previous opposition leader who had been sentenced to death during the Years of Lead, seemed intent that the transitional period pass smoothly, and that the young king take full advantage of the situation to fully put things on the road to reform.

The king is dead. Long live the king!

Many things have changed, Rahhal. Many things. The phone booths have disappeared and have been replaced by phone cards and mobile phones. Teenagers have even started to walk around with multi-ringtone mobile phones. Postage stamp collectors have started to go extinct since email doesn’t require an envelope, or a stamp, or even a mailman. Your Peugeot 103 motorbike that used to take you and Hassaniya to Massira has turned into a Fiat Uno. It’s a used car, but the engine still pulses with determination, roars with power, and moves around with the perseverance of a worker bee. Hassaniya managed to get a driver’s license and has now taken on the role of driver. When you stay late at work you have to take the bus to Djemaa Lfnaa. Sometimes you slip in among some suspicious characters in the collective midnight taxis. And from the heart of the square, you turn toward the nearest alley that will take you to Mouassine.

Rahhal had started to work late more and more in recent years. The spiders of the cybercafe that he managed continued to weave electronic threads into webs until midnight, sometimes until after one in the morning when the weather in Marrakech was hot and the nights of the Red City made it tempting to stay out late.

The customers at the cybercafe were mostly young people. Teenagers. It happened that some middle-aged people would visit the café, too, but not with any regularity. Most of the regulars were young boys and girls, students from the nearby high school. There were college students, too, and a few unemployed people as well.

***

The king is dead. Long live the king.

Long live the multi-ringtone mobile phone. Long live modern technology. Long live blue screens.

When the poor population gets a mobile phone and surfs the kingdoms of electrons, they forget all about their misery. The world becomes as small as a village. It becomes available to people in the cybercafes that have begun to spread like fungus, all at democratic prices. Not too expensive for the poor. Two dirhams for a light, passing visit. Three dirhams for half an hour. Five for a full hour. For the loyal customer, the second hour costs four dirhams, and so on. A few dirhams and a few words of every foreign language is enough for the virtual people of God to surf the multilingual pavilions of blondes. That’s for the guys. As for the girls, a bit of Arabic is enough to make flashing red hearts leap from the Atlantic Ocean to the Persian Gulf.

Long live technology.

As for Rahhal, he was at the heart of it. In the right place at the right time.

He opened a Hotmail account, not to email anyone, but rather, just to have an account with Hotmail. He set another one up on Maktoub, not to use to chat with Arabs online, but rather, because it just made sense for him to have an account on Maktoub. The third one on Yahoo, similarly because it was Yahoo. The fourth? He still hadn’t decided.

All of the cybercafe’s customers were new to the scene. Most of them were still at the discovery stage, which is why whenever a new person came to the shop, he would stand in front of Rahhal to request a computer and a helping hand. This one wanted to open a Hotmail account, that one a Yahoo account, and Rahhal stayed up late opening online accounts for them here and there; a new service that seemed magical to those heading to the cybercafe for the first time. Therefore, he set a price of thirty dirhams. The account was free, but Rahhal made thirty dirhams for every account he opened and the customers found that to be perfectly reasonable. You couldn’t get an online account that did the same thing as a post office box that held letters for the customers in the Massira Post Office for nothing, right? And Rahhal’s mailbox was better because you didn’t have to pay more than the registration fee on the first day for it to remain open for you forever.

Customers came and went, taking turns at the computers and dragging mouses over the desktops. But a small family gradually began to form around Rahhal. Salim was a high school senior dazzled by the new, virtual world. He had two email accounts so far, one with Hotmail and the other with Yahoo. Sometimes he’d come in with his father and sometimes with his sister, Lamia. Always searching for information on the web, and every day needing to print out his search results which he knew how to flaunt in front of his classmates.

Samira and Fadoua would come in together, sit together, and leave together. Specializing in chat rooms, they became a single online persona. They loved to chat with young guys in Arabic, French, and English. Username: Marrakech Star.

“Two in one. Shampoo and conditioner,” Qamar Eddine Assuyuti would tease them whenever he glimpsed them entering the cybercafe. Qamar Eddine was the son of Shihab Eddine Assuyuti, the most notorious Islamic Education teacher in Massira High School, and the one whom the students joked about the most.

“Which one of us is shampoo, and which one is conditioner?” Fadoua would ask in a conspiratorial voice.

“To be honest, I’m still working that out. When I decide that you’re the shampoo, I’ll let you know.”

Qamar Eddine knew all about Marrakech Star, especially since Fadoua and Samira ran to him for help with all of their messages that were in English. He’d explain whatever was unclear in the emails they got from all over, and correct their replies so they could travel across the internet with fewer mistakes.

Qamar Eddine’s English was good. So was his French. But he liked to say over and over, whether anyone asked him or not, that, regretfully, his Arabic wasn’t so good. There never seemed to be any regret on Qamar Eddine’s face when he repeated this confession. In fact, he practically shone with a hidden pride. Did he say it to spite his father, Mr. Shihab Eddine? An Arabic teacher who moved to Islamic Education not out of an abundance of religiosity, but rather out of laziness and a desire to wash his hands of grammar lessons. Islamic Education wasn’t a core subject for science or humanities students. Two hours per week for everyone. A number of students considered that class a break that they’d spend on the sports fields, in front of the school, or at Rahhal’s place in the case of those who could pay the price of skating along the screens’ icy surface and surfing the light’s waves, especially since Mr. Assuyuti didn’t take regular attendance.

***

Qamar Eddine wanted to get out of his country by any means necessary. He was sick of Shihab Eddine and with the boring life he lived at home. He was sick of the college that he only went to rarely now. He was even sick of the damned cybercafe that, it seemed, he had become addicted to. He was sick of Rahhal’s snooping—every time he turned around, he found the rat looking at his screen. He was sick of the history teachers from school who would come en masse to the cybercafe to talk. They didn’t have set hours, but when they honored the place with their presence, they came as a group as if going to the mosque. Each one occupied a computer and rather than riding the waves and surfing, they’d chat as if they were in the teachers’ lounge. They’d tell stories about how much worse things had been in the Hassan II era and about how much better things had become under the young king; that there were more freedoms, that there was a new vitality and initiatives for change. Qamar Eddine wasn’t interested in his father’s colleagues’ stories. He couldn’t see any change at all. And who said he wanted to know how life was under Hassan II? He was young then. And today he felt that he had grown up. He didn’t want to go backward. He had no time to waste on this sort of talk. Qamar Eddine wanted another life. The kind of life he saw in the movies. The kind he saw on television. The kind of life that God’s chosen people were living up north. Qamar Eddine wanted to escape. Emigration is a sacred right. He didn’t understand why he should have to stay in a place that was strangling him, with creatures he didn’t like. He didn’t understand why he wasn’t entitled to cast this whole, irritating world from his days and nights—from his life, his future—and just take off.

***

“Big Brother is watching you!”

Qamar Eddine would repeat this sentence in English from time to time, mocking Rahhal.

“Sorry, sorry, I meant to say, ‘Little Brother is watching you!’”

The cybercafe would shake with laughter.

It had to be admitted that Rahhal’s English was just above nil. As for his knowledge of English literature, it wasn’t much more than what Amelia knew about the Islamic theological teachings of Imam Malik, which is to say, nothing. In any case, Rahhal was a product of the Department of Arabic Literature with a specialization in ancient poetry: pre-Islamic epic odes, poetry from the Umayyad and Abassid periods, as well as from al-Andalus and Morocco. He didn’t even read novels in Arabic, a language he’s very good at, so how could he read them in other languages? And because no one ever explained to him that the reference was to George Orwell’s famous novel, 1984, in which Big Brother watches over everyone, he continued to wonder deep down why Qamar Eddine was boasting about his two brothers—the big one and the little one—in the cybercafe when he only had one sister, who was pursuing her graduate studies in Rabat.

“Little brother is watching you!”

Qamar Eddine’s prodding didn’t irritate Rahhal at all. Qamar Eddine was protesting the way Rahhal treated the customers’ screens in the shop as private property as he fixed his mouse eyes on them as he pleased. That annoyed Qamar Eddine to no end during the first stage of his virtual life, when he was still addicted to porn sites. To this day he hates it when people snoop around his blessed sites. That’s why he began to avoid illustrated pages that included pictures of churches, icons, and ecclesiastical drawings. Mostly, he would take texts and paste them onto a blank page and then read them in Word at his leisure. And when he was done, he’d toss the file into the trash bin and log out.

But in Rahhal Laâouina’s kingdom, there was no place for trash bins. As soon as the last customer would leave after midnight, Rahhal would take a few minutes, sometimes more than an hour, to examine the computers. He would inspect each and every one. He would scrape around inside and tear the cover off of the secrets of those who have hidden themselves in the digital shadows. A number of them left their accounts open. Same with members of online forums. For example, Brother Abu Qatada often minimized the screen and left after hearing the call to the evening prayer, leaving the forum page open with the discussion between brothers continuing along: one time about the need to kill and sacrifice the self should an occupier come to a Muslim land. Another time about using the fraudulent electoral system as a means to gain control and win government posts. This time the discussion was heated, and always about elections. The brothers in God strongly objected to the candidates’ heretical self-promotion, and likewise to the notion that all members of society have an equal vote, no matter their degree of learning or religious devotion. As for Abdelmessih’s Holy Scriptures, Rahhal would retrieve them from the trash bin and transfer the Arabic ones to his personal computer so he could go over them leisurely the following day.

This amounts to extra work that Rahhal does before closing up, except that he’s the one who opened up the accounts for all the club members in the first place. His prodigious squirrel memory stores everyone’s login names, real and made-up, and remembers all the passwords. Veils are lifted and the secrets behind them revealed. That’s how Rahhal Laâouina knows everything about the flocks of his happy, cybernetic kingdom. Even the Nigerian community in the Atlas Cubs Cybercafe had their secrets revealed to him after they transferred their activities to the electronic realm. Amelia and Flora are gay, but they prostitute themselves to men right now as they wait for the emerging and promising women’s market in Marrakech to open up. And Yacabou works for them as an escort, a personal guard, and as an intermediary. As for his relationship with Flora, it’s a cover, silly Qamar Eddine. It’s just a cover.

Yeah, Rahhal. You see them moving in front of you like puppets. None of them knows that they’re in your pocket. Their real and made-up names. Their interior and exterior lives. Their dreams and their delusions. Their ruses and their wild, made-up tales. Their innocent virtual friendships and their illicit electronic adventures. Everything is in your pocket, Rahhal, but you’ve got to be smart about it. Be extremely careful that these secrets remain hidden. Keep them to yourself, you scrawny squirrel. Otherwise, if, for example, Abu Qatada found out that Qamar Eddine had lost his way so much and deviated enough from his path and his religion for his name to become Abdelmessih, and that the two Nigerian girls were ladies of the night, he’d call for jihad right then and there; a crushing war would erupt in the cybercafe. So Rahhal enjoyed spying on the members of his new family with just enough care to give each one of them a feeling of total safety. Besides, they were at home and in the embrace of their happy family here in the virtual jungles of the Atlas Cubs Cybercafe.

Translated from the Arabic by Alexander E. Elinson

Click here for more information about the book.

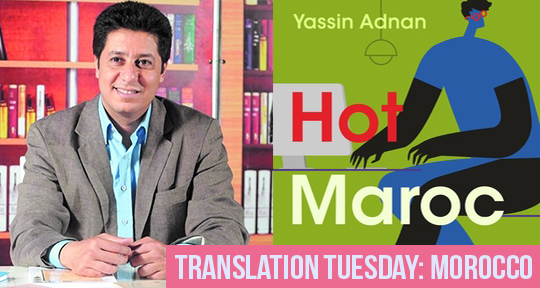

Yassin Adnan is a Moroccan writer, editor, and journalist. He is the editor of Marrakech Noir and the author of four books of poetry and three short story collections. Since 2006, he has researched and presented his weekly cultural TV program Masharef (Thresholds) on Morocco’s Channel One, and currently hosts Bayt Yassin (Yassin’s House) on Egypt’s Al-Ghad TV. Hot Maroc is his first novel.

Alexander E. Elinson is associate professor of Arabic language and literature, and head of the Arabic program at Hunter College, CUNY. He is the author of Looking Back at al-Andalus: The Poetics of Loss and Nostalgia in Medieval Arabic and Hebrew Literature. His translations include two novels by Youssef Fadel: A Beautiful White Cat Walks with Me and A Shimmering Red Fish Swims with Me.

*****

Read more from Morocco on the Asymptote blog: