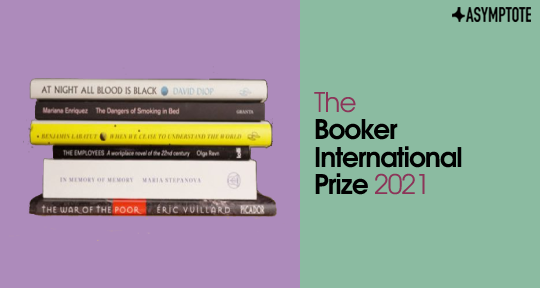

With the announcement of the Booker International 2021 winner around the corner and the shortlisted titles soon to top stacks of books to-be-read around the world, most of us are harboring an energetic curiosity as to the next work that will earn the notoriety and intrigue that such accolades bring. No matter one’s personal feelings around these awards, it’s difficult to deny that the dialogue around them often reveal something pertinent about our times, as well as the role of literature in them. In the following essay, Barbara Halla, our assistant editor and in-house Booker expert, reviews the texts on the shortlist and offers her prediction as to the next book to claim the title.

If there is such a thing as untranslatability, then the title of Adriana Cavarero’s Tu Che Mi Guardi, Tu Che Mi Racconti would be it. Paul A. Kottman has rendered it into Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood, a title accurate to its content, typical of academic texts published in English, but lacking the magic of the original. Italian scholar Alessia Ricciardi, however, has provided a more faithful rendition of: “You who look at me, you who tell my story.” This title is not merely a nod, but a full-on embrace of Caverero’s theory of the “narratable self.”

Repudiating the idea of autobiography as the expression of a single, independent will, Caverero—who was active in the Italian feminist and leftist scene in the 1970s—was much more interested in the way external relationships overwhelmingly influence our conception of ourselves and our identities. Her theory of narration is about democratizing the action of creation and self-understanding, demonstrating the reliance we have on the mirroring effects of other people, as well as how collaboration can result in a much fuller conception of the self. But I also think that there is another layer to the interplay between seeing and narrating, insofar as the act of seeing another involves in itself a narrative creation of sorts; every person is but a amalgam of the available fragments we have of them, and we make sense of their place in our lives through storytelling, just as we make sense of our own.

I have started this International Booker prediction with Cavarero because I have found that this year’s shortlist—nay, the entire longlist—is explicitly focused with questions of archives, loss, and narration: what is behind the impulse to write, especially about others, and those we have loved, but lost? Who gets to tell our stories? It is a shame that Adania Shibli’s Minor Detail, translated by Elisabeth Jaquette—as one of the most interesting interjections on the narrative impulse—was cut after being first longlisted in March. The second portion of Minor Detail sees its Palestinian narrator becoming obsessed to the point of endangerment to discover the story that Shibli narrates in the first portion of the book: the rape and murder of a Bedouin girl, whose tragic fate coincides with the narrator’s birthday. This latter section of the book is compulsively driven by this “minor detail,” but there is no “logical explication” for what drives this obsession beyond the existence of the coincidence in itself.

I think one could give an answer to the question raised in Minor Detail by looking at a title that was actually shortlisted: Maria Stepanova’s In Memory of Memory, translated from the Russian by Sasha Dugdale. Stepanova too is concerned with the act of remembering and storytelling, and its essayistic nature serves as a sort of lens through which almost the entirety of the shortlist can be analyzed. In Memory of Memory explores not only the nature of memory, but the human penchant for saving the most insignificant scraps and family members from the oblivion of forgetfulness, even if only temporarily. According to Stepanova, this desire is often fueled by an implicit belief in the great unjustness of death, and also the urge to finding meaning behind coincidences—between the scattered fragments of our lives in the hope counteracting the randomness of existence, to prove that we are here for a reason. And you can see these impulses at play in Minor Detail, though the death in question that haunts the second narrator is as unjust as it gets.

In Memory of Memory has been at times compared to Annie Ernaux’s The Years (translated by Alison L. Strayer), given that both play with genre and delve into notions of remembering and forgetting. But Ernaux is more earnest and playful in her conception of memory. If memory fails her, if it feels flimsy, she still manages to find joy in the small, tangible things that marked a community: ad jingles, make up brands, cheesy song lyrics. Stepanova, on the other hand, is cautious, cynical almost. Indeed, what starts out as a more traditional story—Stepanova wading through the hordes of stuff her recently departed aunt has left behind—is upended almost immediately. Only a few chapters in, the text sees Stepanova return to her ancestral village to visit what she believes to be the place where her great-grandparents had once resided. She can feel their presence everywhere—it resonates with the hidden ties that bind her culturally and biologically to that place. Yet, on the train back, she is informed that the place had nothing to do with her family after all. The connection Stepanova had felt had been an illusion. In the face of self-deception, how can one find comfort in the malleability of memory; in our self-delusionary tendency to find patterns everywhere?

The power and danger of narrative remerges in Olga Ravn’s stunning and poetic The Employees, translated from the Danish by Martin Aitken. Sometime in the distant but somehow still recognizable future, a crew of humans and humanoids work together in the Six-Thousand Ship, a spaceship orbiting the planet of New Discovery. Life on the ship is heavily structured, all revolving around some cryptic work the crew is conducting. The environment the workers inhabit is sterile, from the food they eat, to the clothes they wear, to their non-existent relationship with one another. Of course, this description is me filling in the gaps as a reader. For The Employees is told in a series of disparate, non-linear witness statements gathered after some strange objects found in a valley on New Discovery disrupt the regimented nature of the life on the ship—and it’s not just the human beings who become affected.

An attempt to describe the plot of The Employees feels futile. All I want to do is quote the many highlighted bits that I keep returning to on a regular basis, lines of poetry that I keep repeating to myself, such as: “Is this a human problem. If so I’d like to keep it?” This is an interactive piece of work; the objects that unleash the transformation of the crew are inspired by Lea Gulditte Hestelund’s sensual exhibition “Consumed Future Spewed Up as Present.” Upon contact with these objects, the crew begins to see themselves as prisoners; human beings feel nostalgic, and humanoids experience emotions they weren’t programmed to feel—emotions that are seen as anomalies to be fixed with the next update.

There are two conclusions to The Employees: on the one hand, the corporation at the inception of the whole project writes a statement detaining the failings of the operation in a methodical, business-like manner that takes no pity on the humans or humanoids sacrificed. Here we see how narrative and the search for meaning can be co-opted, twisted by the capitalist machinery in which the deviations that make us human are seen a problem to be solved for the sake of productivity. And yet, an Appendix to this report offers a glimmer of resistance, as the last humanoids, aware that they will soon be terminated and reuploaded after improvements, make the conscious decision to choose oblivion and death in the beautiful valleys of New Discovery instead. Still, the question of remembrance persists: “How can we live with the knowledge that none of these days will be remembered by anyone, not even ourselves?” an unnamed subject asks.

Save for some contrarians, there was a general sense of shock when Eric Vuillard’s The War of the Poor, translated by Mark Polizzotti, was shortlisted. Part of me wonders if the negative backlash among the reader and reviewer spaces might have never manifested had this book not been included in the longlist—perhaps people would have enjoyed it more if they didn’t feel like it had taken the spot of a more “deserving” title (of which I can think of at least half a dozen). The book simply feels rather average; it’s a traditional story told in a traditional way, an essay on the life of Thomas Müntzer, a little-known figure of the Reformation who defied both the Catholic Church and Martin Luther. Vuillard weaves a rapid tale of the path that culminated in the figure of Müntzer, a repeated history of religion as not an opiate of the masses, but rather a catalyst for revolt. I preferred the book in its last pages, where Vuillard talks about martyrdom as a trap, set by our need for stories to give events and our lives meaning. Yet, despite this warning, the last sentence of The War of the Poor is almost a promise—Vuillard’s pledge that he shall continue to tell the tales of the oppressed, of martyrs, of victories and losses. This impulse remains stronger than any knowledge of ultimate futility, for, as Ernaux says in The Years, “All images will disappear.”

A line from Camus’s The Myth of Sisyphus (in Justin O’Brien’s translation) has stayed with me since I first read it more than a decade ago. In one version of the myth, as Camus tells it, Sisyphus asks his wife to throw his body in the public square after his death. She does, and he is then “annoyed by an obedience so contrary to human love.” An obedience contrary to human love is also the catalyst behind David Diop’s At Night All Blood is Black, translated from the French by Anna Moschovakis.

In the trenches of World War I, Alfa, a chocolate soldier, witnesses his childhood friend and more-than-brother, Mademba, die in agony from a battle wound while Alfa refuses to end his misery, bound by “human” conventions against killing. Yet, Mademba’s death is also Alfa’s liberation, forcing the latter to realize the inhumanity of the human-made rubric that had prohibited him from ending Mademba’s pain when he could. Undone by grief and untethered to any human code of ethics, Alfa becomes a sort of demon haunting the battlefields and nightmares of soldiers on both camps, as he begins to select one German soldier after another to disembowel each night. But there is no respite to be found in violence, and throughout the narrative Alfa begins to lose his sense of self. The stories told about him feed the racist stereotypes that the French had relied on to terrify German soldiers—the sinister operation behind their selection of the thousands of colonized Black men serving in the trenches. And the realization of his own function in this war pushes Alfa deeper into madness.

With the exception of The War of the Poor, the titles above represents some truly stunning pieces of writing that had my heart and brain abuzz. As for perhaps my one controversial opinion about this shortlist—considering that this book has topped rankings of book clubs, held a consistently high rating, and is likely the considered winner for most people who have read a good chunk of the shortlist—it concerns Benjamín Labatut’s When We Cease to Understand the World, translated by Adrian Nathan West. I understand why this book is loved; I think it’s the same reason movies about misunderstood geniuses continue to win and be nominated for Academy Awards (think A Beautiful Mind, or more recently The Theory of Everything). After all, what is more human than losing your mind over the fact that we will never understand the universe, all rendered in writing as polished and soaring as a Hans Zimmer score?

When We Cease to Understand the World follows a number of twentieth-century male scientists, mostly working around the physics and mathematics of a theory-of-everything. There is a short-story-like quality to these fictionalized biographies, and after a while the narratives become formulaic: brilliant mind grapples with hard question, has mental breakdown. I think this book might have worked better had it been published a decade ago; for present day, it feels a bit dated in its tackling of existential quandaries, told with an acknowledgment to the human limits of scientific knowledge. The whole book is somewhat of a less precise and more metaphorical version of a Carlo Rovelli or Brian Green popular science work about time or string theory. The writing is beautiful—Adrian Nathan West has done a marvelous job with the translation—but good writing can only take you so far.

Talking about a tiring conceit, short story collections always have a rough time at the Booker International, so I am wary to consider Mariana Enríquez’s The Dangers of Smoking in Bed, translated by Megan McDowell, as a potential winner. Don’t get me wrong—it’s an enjoyable book, brilliantly presenting horror in flashes of poetic detail, and vividly depicting how the most horrifying things are not otherworldly, but the moments of conscious cruelty: when a group of jilted teenage girls leave two lovers to be presumably eaten by feral dogs, or when a whole set of family members decide to unburden their fears onto the youngest daughter for the sake of their own freedom. But perhaps because this was Enríquez’s first collection of stories, the set feels uneven, at times tentative, like she is still trying to figure out her craft, relying perhaps on the shock value of a macabre twist that is not entirely unpredictable. It’s by no means a bad book, but it pales in comparison to the rest of the shortlist.

In The Tidal Zone, Sarah Moss writes that “[f]iction is the enemy of history. Fiction makes us believe in structure, in beginnings, and middles and endings, in tragedy and in comedy.” This persistent but deeply buried quest for life’s linearity does indeed structure our lives and relationships, but I also think that the best fiction upends this distinction. It reminds us precisely that meaning is constructed—that it can be unsettled, weaponized. Or that our quest for meaning can be moving, but it can also be debilitating. In Memory of Memory certainly grapples with these questions head on, and At Night All Blood is Black has the sort of narrative power that questions our constructed cultural mores—how they serve to subsume our humanity. I think of both of them as worthy contenders, but there is no clearer winner to me this year than The Employees. It is beautifully translated; it is tragic and hopeful and as human as the giving of freckles to a humanoid constructed only for the purpose of eternal labor. Any other title winning would be settling.

Barbara Halla is an assistant editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in history from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: