The vast contours of the internal landscape are painted with delicacy and precise restraint by Argentine writer Federico Falco in A Perfect Cemetery, our Book Club selection for the month of April. With his studies of life on the rural outskirts, the author gently but determinately probes the stoicism and stillness of human existence, and how a perceptible smallness and inwardness can betray a complex and considered philosophy of living. In light of our days being increasingly filled with aspirational stimuli, Falco’s work is a respite of care, of untangling the secret threads that connect the nature of being with the ways of the world.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive Book Club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom Q&As with the author and/or the translator of each title!

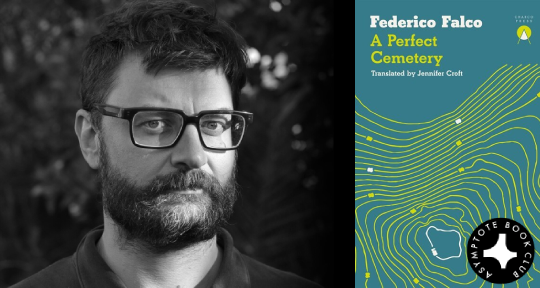

A Perfect Cemetery by Federico Falco, translated from the Spanish by Jennifer Croft, Charco Press, 2021

In five impeccably crafted short stories, Argentine writer Federico Falco displays his distinctive gift for distilling and dramatising the quietude of rurality to generate—from such ostensibly minor landscapes—an intense and varied portrait of life on the geographical periphery. Take, for example, the titular story: Víctor Bagiardelli, a scrupulous engineer of cemeteries, is commissioned by the mayor of small town Colonel Isabeta to build their first cemetery. Mayor Giraudo no longer wants to have the town’s dead sent to nearby Deheza to rest, but he meets resistance from the town council, who accuses him of abusing public funds in the interest of ensuring that his father is buried at home. “A bunch of ignoramuses who care nothing for progress,” Giraudo grumbles of a council whose inertness, he believes, only serves to secure the town in its provinciality.

Giraudo’s description—though unkind—is perhaps not an inaccurate assessment of Falco’s characters who, in their locality, shun the promise of progress. They are searching, instead, for a place to rest. Whether a literal burial place at the end of one’s life, or simply a spot to retreat to in order to go on living—the quest for silence and solitude constitute the central drama of their phlegmatic dispositions. After all, ‘cemetery’—from the Greek koimētḗrion—refers first and foremost to a sleeping chamber. A perfect cemetery, as the dark comedy of the collection’s title suggests, refers then to an ideal place for rest, recuperation, and languor. Read together, Falco’s fiction cohesively articulates—as the book’s intellectual and emotional pleasure—retreat as a way of life against the hedonism of pursuit.

Meanwhile, even as Mr Bagiardelli oversees the cemetery’s construction on the hillside down to the last weeping willow, and residents are eager to reserve the best spots for themselves—the 104-year-old Old Man Giraudo refuses to die, much to his son’s consternation and the engineer’s chagrin. Even the pinnacle spot in the cemetery, under the shadow of a majestic oak, is unable to convince the centenarian to rest reliably, as he actively plots against not just the cemetery’s but his life’s completion; as such, we come to understand how the ideal resting place never comes easy for these characters. That is, the only legitimate form of pursuit for the people who populate Falco’s landscape is one that is restlessly in search of stillness; a philosophy of solitude that knows how a privacy to live and die can be a hard-won thing.

It comes as no surprise, then, that their ideal spaces of respite are often ensconced in the isolated environments detached from the noise of human activity. The opening story, “The Hares,” is remarkable for conjuring, from the onset, a descriptive landscape that empties the short story of the human ego: we follow an enigmatic “king of the hares” through a pine forest for five whole pages, and because of his animal-like movements, cannot quite make out his humanness. Our protagonist eventually reaches an altar made of “adornments of honey locust pods and wildflowers, spines, and scapulae interwoven to create a pyramid,” and kneels silently in front of it, in a state of spiritual repose. The encounter has an aura of the numinous, appearing as an invitation for the reader to commune beyond the human—to reimagine human sociality with the non-human, as life around him responds to his ritual of rest:

The hares didn’t take long. They arrived and lined up in a half-circle, ears pricked, the slits in their noses probing the air: all the hares from the meadow. At that moment the sun shot up over the mountain, a diagonal ray dyeing their coats orange.

One of the most affecting powers of Falco’s prose is his uncanny ability to world an ecological landscape, at once anchored in his native province of Córdoba and tethered to an imaginary of unnamed sierras, forests, and rivers, stretching across his stories like an unbroken scroll. These are spaces of respite not just for his characters but, one suspects, also for readers whose literary imagination might be locked in the urbane, and who wish to seek flight into other literary ecologies. Indeed, we later learn that the king of the hares had retreated from his nearby town to the meadows, and can occasionally hear, from his new settlement, the faint, faraway sound of “mostly barking dogs, but gusts of music, too, when there were weddings, and, on New Year’s Eve, the thunder-flashes, then the dazzle of the fireworks.” They are remainders of an integrated and humanly social life, cast to the periphery as a minor act to the symphony of a less populated—but perhaps infinitely more ecologically attuned—landscape he now inhabits and lives.

In Falco’s world, specific landscapes enable his characters to inhabit ways of seeing that might prove disorienting when they are abruptly uprooted from their surroundings. “Forest Life,” for instance, follows the story of Old Wutrich as he is forced to marry off his daughter, Mabel, to live elsewhere as their pine forest home is gradually being logged by the industrious lumberjacks working on the horizon. When a Japanese man, Sakoiti, agrees to marry Mabel as well as pay for the old man’s stay in a nursing home (equipped with a cinema and a dance hall), Old Wutrich begins to recall the four hundred and fifty thousand pines he planted back home. Mabel herself finds, in her new home amongst other Japanese immigrants, her eyes becoming “lost in that ground with a single tree.” Over the course of the story, a muted bond develops between Mabel and Sakoiti, not over their marriage—which suffers from one-sided lovelessness—but out of a mutual recognition that their union was only possible because they were uprooted from a prior landscape through histories of immigration and deforestation, to live amidst this one, which will inevitably supersede their past.

We endear to Falco’s characters not because they offer themselves up to us transparently, like so many verbose and erudite narrators and protagonists of contemporary fiction. Instead, in their calculated reticence, these characters often only speak to sufficiently express what they mean. One walks away from these stories with the rare feeling that their allure emanates from their intense guarding of one’s interiority; we root for their restraint and reservation—their allegiance to place, not people—and are rewarded when, in carefully timed moments, they put aside their enigma, allowing us a glimpse at the tenderness that had hitherto remained private. This narrative composure is most evident in the stories’ sensitive evocation of sexuality, where sexual connection is often established only to end in a repressed expression of tenderness ranging from polite rejection (“I’m not used to that kind of thing anymore,” the king of the hares say to a lover who visits), to a reluctant relenting (“Just for a little while,” says Mr Bagiardelli to a suitor), or a patient deferral (“Next time,” Mabel says to Sakoiti, “I’ll relax, I promise.”). These are often heartbreaking in their very austerity—where such fragile connections are being sought, they convince us not so much of love but its possibility.

Man Booker International Prize-winning Jennifer Croft writes in the epilogue to her translation: “It was the emotional clarity of the communication between characters in these stories that I most wanted to preserve in my translation.” If Falco’s writing has been praised for his evocative exploration of the Argentine interior, Croft’s lucid translation bequeaths Anglophone readers a writer who himself has an adept gift of excavating the psychological interior as it relates to the exterior, the environmental, and the ecological. Attuned to both the expansiveness of the world beyond the self, as well as the trickle of detail and of daily human living, these sweeping stories form an accomplished, cinematic pentalogy that immerses the reader even as it asks us to keep a distance, to give privacy its own mysterious hiding place.

Falco, who was named by Granta in 2010 as one of the “best young Spanish-language novelists,” proves his mettle here with the short story genre: his patient, affecting storytelling has the ability to stretch his form and setting’s assumed smallness and quietness into capacious worlds. Here is writing which transforms provincialism into the province of fiction, drama, and ultimately, nourishment, stories which have perfected the art of refusal. They teach us to say no to the lure of a perfect cemetery, to instead wrest back autonomy in the decision of one’s eternal company, and in where one gets to call his resting place. They teach us not to forfeit that sovereignty even in the afterlife, and certainly not while we are up in this business called living. If anything, they teach us to keep looking.

Shawn Hoo’s poems have been published or are forthcoming in journals including Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, Queer Southeast Asia, OF ZOOS, and Voice and Verse Poetry Magazine, as well as anthologies such as A Luxury and EXHALE: An Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices (both Math Paper Press, 2021). He graduated from Yale-NUS College with a BA(Hons) in Literature and was a Teaching Assistant Trainee (English Literature) at the National University of Singapore. He is assistant editor at Asymptote, and can be contacted via his email here.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: