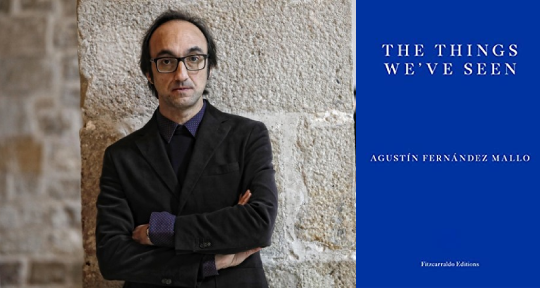

The Things We’ve Seen by Agustín Fernández Mallo, translated from Spanish by Thomas Bunstead, Fitzcarraldo, 2021

In 1989, an extraordinary exhibit opened at the Zoology Museum of Barcelona. Visitors flooded the unveiling of a retrospective on the work of German zoologist Peter Ameisenhaufen, who disappeared under mysterious circumstances in 1955, and his assistant, Hans von Kubert. The exhibit consisted of the meticulous field notes, drawings, photographs, and x-rays of the rare animals the scientists discovered on their travels: Perrosomus, a desert rabbit with exaggerated incisors, Squatina squatina, a leathery sea creature with grotesquely humanoid features, and Solenoglypha polipodia, a snake with birdlike legs running along the length of its body.

If this is starting to sound far-fetched, it’s because it is.

Ameisenhaufen and von Kubert are the alter egos of Catalan photographers Pere Formiguera and Joan Fontcuberta, and the exhibition was, in fact, an artistic one. Designed to question the intentions of photography and its rich potential for deception and fakery (around 30 percent of those attending the inauguration with university degrees said that they believed the animals were real), the exhibit asked visitors to examine the blurred line between fact and fiction and see what truth they could extract.

In much the same way, Agustín Fernández Mallo’s latest novel in three parts, The Things We’ve Seen, sets the mind racing with blurs and glitches—periodic and perturbing reminders of just how malleable our reality, both past and present, can be in the hands of an expert. The English title of the book is taken from a line of poetry by Beat poet Carlos Oroza, which serves as one of the epigraphs to the novel, and subsequently appears with mantra-like regularity:

It is a mistake to take the things we’ve seen as given

With this as his cornerstone, Fernández Mallo creates an intricate network of information and stories, which sprawl outward and intersect seemingly at random, to form a vertiginous commentary on history, war, memory, and our interconnected, twenty-first century lives. In the first part, a writer not unlike Fernández Mallo himself attends a conference on the small Galician island of San Simón, where a group of Twitter-obsessed creatives and thinkers reflect on digital networks. He is accompanied by Julián Hernández, a real-life man who is part of a real-life punk band, Siniestro Total. With the mention of actual people, places, and events so early in the novel, it is tempting to think that what follows will be a species of essay. However, The Things We’ve Seen is published by Fitzcarraldo, whose color-coded covers give the game away (white for essays, Klein blue for fiction). Far be it from me to judge a book by its factuality, but in this case, it is as though the author is daring the reader to believe, to latch on to the recognizable markers of our shared world.

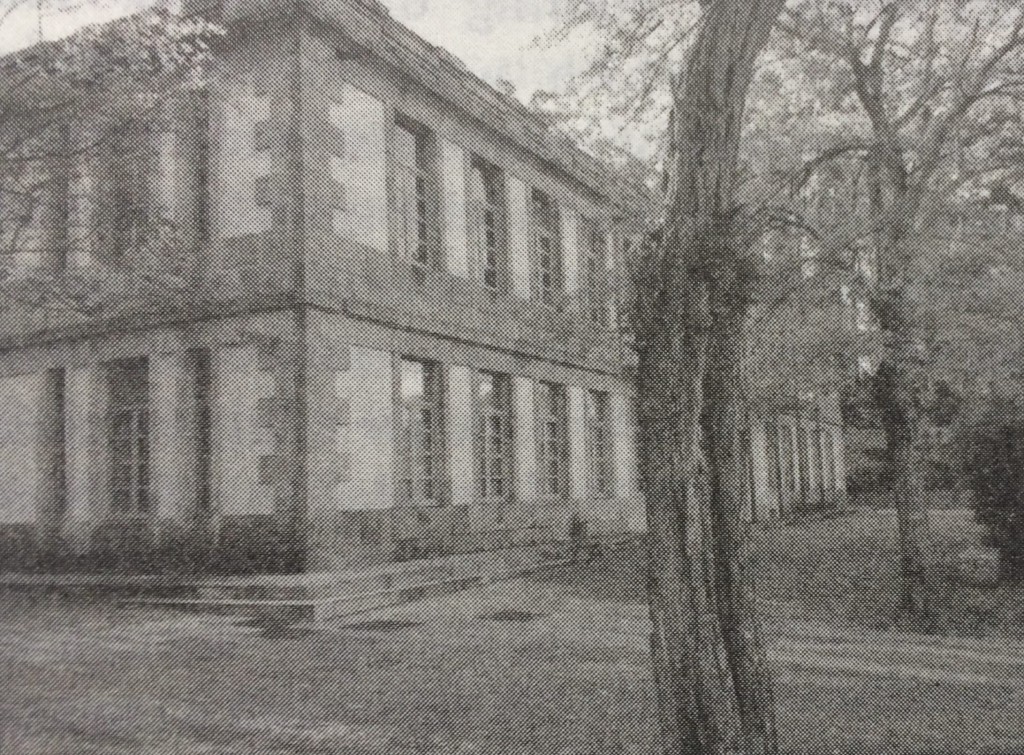

Like Fontcuberta and Formiguera, Fernández Mallo isn’t afraid to use pictures alongside his words as proof of their verisimilitude or lack thereof. Once on the island, the writer sets about taking photographs to match those he finds in a book detailing San Simón’s dark history as a Francoist concentration camp. A line of prisoners stands against the wall of what is now an unassuming pavilion. Past and present sit together on the page with unsettling proximity, much like the fake and the real.

After the island conference has finished, the writer stands on the beach with his colleague and suddenly echoes the novel’s other epigraph, Dorothy Gale’s eternal words from The Wizard of Oz, ‘“Julián,’ I say, ‘I’ve a feeling we’re not on the island anymore.”’ At this, a series of dizzying, dreamlike narratives unravel before us. The writer later returns to the island alone, only to be haunted by the ghosts of the prisoners held there during the Spanish Civil War. Between yearlong lapses in memory, he travels to New York, meets a punkish artist who specializes in war, listens to a Dalí lookalike (or perhaps he’s the real deal?) talk about his theory of trash, becomes obsessed with a baker who may or may not have been a prisoner on San Simón, and eventually winds up in Uruguay, carrying a handwritten manuscript of poems by Lorca (the ghost of whom, by the way, wanders around Central Park at night). The writer proceeds as though attempting an exorcism, dragging flesh and blood relics to the present, to prove they existed without relying on the images which, as we’ve seen, can so readily be manipulated and manipulative.

Each piece of the triptych has a different narrator, and each, like the writer, is dogged by doppelgängers, incessantly repeating motifs, and prolonged bouts of daydreaming, which draw them to, and perhaps over, the edge of insanity. In the second part of the book, we meet Kurt Montana, the fourth astronaut aboard the Apollo 11, who has been all but erased from history due to his role behind the lens as the voyage’s photographer. Whether he is delusional or from a reality parallel to our own no longer matters—he is simply part of the network.

Despite trouble with his memory, Kurt leads us through feverish reconstructions of key moments in his life, which range from the mundane to the intensely psychedelic. The anchoring factor here though, the novel’s ground zero as we come to realize, is war. From his mother’s visions of the massacre at Guernica to the flashbacks of his crimes in Vietnam, this entire chapter could be a hallucinogenic one-man attempt to write himself into world history. He even describes his crude efforts to reproduce an image of his younger self, with his face as it is now:

what I do is I take the printouts, cut around my face and then stick my current face onto a photo I’ve got on the wall back at home, a photo Armstrong took of me, a private moment you understand, something the public has obviously never seen: it’s of me walking on the moon

Coincidentally, in Joan Fontcuberta’s 1997 exhibition Sputnik, the photographer edited a Soviet version himself into a fictional space mission. Again, past and present are merged photographically, only this time, in the same body.

In the final part, the narrative network swoops back around to a woman in Normandy, who is making a pilgrimage after the mysterious disappearance of her partner, a familiar-sounding writer. She walks the beaches of the D-Day landings, thinking of the lives extinguished there, and is plagued along the way by images of contemporary life, news flashes such as the migrant crisis in Calais, and Marine Le Pen’s election posters. We are once again thrown between past and the present, and it is here perhaps that the novel reaches its most coherent stage, despite the soft-focus through which reality is presented—a style that translator Thomas Bunstead has clearly mastered. Although Bunstead must be intimately familiar with Fernández Mallo’s prose by now, having translated his critically acclaimed Nocilla Trilogy, his translation is nonetheless impressive. The writing is disorienting, almost aggressive in its cyclical litany of motifs, and the reading experience suggests an at times excruciating translation process.

In a book so full of repeated sounds and pictures, I found myself beset by a phrase I heard last year, in a virtual lecture by Judith Butler via the Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid: “The dead should not be left to bury the dead.” This was Butler’s closing statement, as her hazel eyes and neat bookshelves were broadcast live across many hundreds of screens, virtual yet real. Similarly, The Things We’ve Seen reminds us that, like the writer on the island, the fourth astronaut, and the wandering pilgrim, we are duty bound to summon the ghosts of the past, whether through technology, art, or pure imagination. In doing so, we all take our place in the network.

Maddy Robinson is a freelance writer, editor, and translator living in Madrid. She is one of Asymptote’s Spanish social media managers.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: