Our Book Club selection for the month of March comes from one of Brazil’s most powerful contemporary voices. With Antonio, Beatriz Bracher brings philosophy and narrative in a deeply ruminative and immersive expedition through familial lineage, uncovering the various fragments of a tumultuous paternal relationship in order to understand the myriad forces that carries an individual from their origin to their present.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

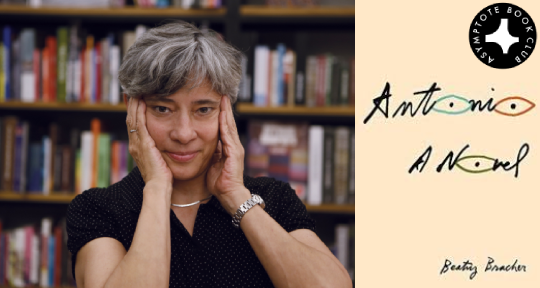

Antonio by Beatriz Bracher, translated from the Portuguese by Adam Morris, New Directions, 2021

“The spectators were part of the show, but they only realised it once they had gone by.”

To read Antonio is to become part of its story. In the conversational style that has become one of Beatriz Bracher’s calling cards, the narrative begins in a direct address to the reader, immediately situating us as characters for whom the story is told, as though one was crowded around a fireplace, listening to a relative tell stories from an armchair. Adopting the same hushed tones and subtle drama of the fireside orator in her writing, Bracher crafts a layered story which brims with mystery and tension. Effortlessly weaving her way through points of obscurity and shocking revelation, she plays with the reader-turned-listener as she leads us through the undulating landscape of a murky family history.

Moving away from our sheltered position at the feet of the narrator, we do not remain passive listeners in a safe domestic environment but active participants in an unsettling journey ascribed with a name and a character—Bracher uses a strikingly intimate second person narrative to address us as Benjamim, the son of Teodoro, the grandson of Xavier, and the father-to-be of Antonio. Benjamim’s family history is uncomfortable; he seeks to uncover the story of his father’s self-exile from São Paolo to the remote countryside, where his mental illness worsened dramatically, leading to his premature death when Benjamim was a boy. Centering the father-son relationship, Bracher follows the male line to interrogate the paternal bond in a way that provokes and disturbs. The reader-as-Benjamim anchors the novel, which flips between perspectives as different speakers—Teo’s friend Raul, his grandparents’ friend Haroldo, and his paternal grandmother, Isabel—provide monologues in response to Benjamim’s questions.

Named for Teo’s dead brother, we—as Benjamim—take the role of the only living man in our family. Beginning with the questions surrounding the death of our namesake, we provoke answers and begin to scrape away at a concealed history. Teodoro and Xavier were driven mad by circumstances that unfolded from the death of the baby Benjamim and his mother. Their spectral presences bind Teo and Xavier in their lives and in their deaths. As Benjamim, our questions are both active and invisible—much like these ghostly figures. They are given shape by spoken acknowledgement, problematized and patiently answered. Although the narrators “know [we] get annoyed . . . if [we are placed] at the center of the narrative,” we are undeniably there—alongside our dead namesake who haunts the novel in more ways than one.

Bracher compiles a chronology of fragmented testimonies, presenting the life of father and son in parallel whilst offering insight into issues of class and politics, which evolve in tandem with their story. Bracher asserts that, in her novels, setting is as much of a character as the people are, and that much is true for Antonio: family history is set to a backdrop of social turmoil, an “environment of fracture and frustration” that sees itself replicated within the family, and on an individual level by Teo and Xavier. The choices that Teo and Xavier make, to immerse themselves in extreme rurality and flee from their middle-class urban lives, are inescapably linked to the politics of the world. As Isabel so aptly tells us, “the world and the choices a person makes in life can also lead to madness.”

There is a pervasive urgency that underscores the conversations and permeates the novel as a whole—an urgency which bleeds into the pace of reading. Adam Morris’s translation navigates the unpredictable turns of the story in a way that amplifies the suspense so integral to it. Morris, a longtime translator of Bracher’s work, preserves her characteristically colloquial language. He retains her subtlety and intimacy. In doing so, he also maintains each individual voice noticeably and recognizably, so much so that we can identify who is speaking even without the chapter titles. Isabel, for example, is formal and restrained, while Raul’s speech is constantly punctuated by corrections, sudden thoughts, and rhetorical questions: “Time flies, it’s true—life goes on,” he tells us at one point. He later asks us: “I kicked your father out of my house. You realise what that means?” Through his translation of this specificity, Morris transmits the differences in class, region, and politics that distinguish each character, ultimately influencing their perspective of the shared history that they tell.

We bear witness to an invented family history; in spite of the fact that it is a work of fiction, Bracher’s writing carries a pervasive truth and a sense of factual realism in its tone. She herself has said that she lifts her inspiration from reality, relying on interviews as preparation for writing. As she explained in an interview with BOMB, they give her “the words, the grammar, [and] the syntax” that allow her to convincingly occupy such a variety of voices and personas in her writing. Yet, there is a quasi-mystical ambiguity that rises from the fragmented accounts, conflicting truths, and shifting perspectives, compounding the mystery of Xavier and Teo. Their stories are connected by a string of coincidences and eerie similarities, transcending their blood relation to forge a metaphysical inheritance that passes from father to son—their lives appear as one, a cycle doomed to repeat itself: Haroldo observes that

Xavier had the same obsession and passed it on to your father. Sometimes I see them as two demagogues, one abandoned by his people, the other devoured by them. Reinventors of the world who left only a void. Their method of isolation was establishing themselves in the midst of other people, laying their heads to rest in foreign places, wading into places other than their own. Your father went too far and too fast.

Two wanderers share the same fate, existing together yet separate. With Teo inheriting not only illness but a way of life from his father, Bracher vaguely nods toward the uncanny, peeping out from behind confrontational realism.

Bracher plays masterfully with the dynamic of seeing and not seeing. Excerpts of conversation and memories obscure as much as they reveal. She hides and then illuminates moments, people, and revelations so that we experience the story as Benjamim: we are shocked, confused, unsure, and irate, just as he is. Various narrators chastise Benjamim for his impatience or anger just as I was guilty of those very reactions, reinforcing the synthesis between reader and character. “Now hold on, listen,” Isabel firmly warns us—a stark contrast to Raul’s sharp rebuff: “Don’t get short with me, Benjamim,” which he follows with a string of curses.

Bracher puppeteers the narrators in a quietly theatrical performance that situates us at the heart of the story. Like children crowded at her feet, we are absorbed by her words. Yet this story is less dramatically entertaining than sophisticated, subtle, and slightly devastating, with no real resolution provided at its close. We, as Benjamim, are left with a patchwork of family history. Closing the book, we react as he would: with dissatisfaction, some sadness, and, more than anything else, a lasting feeling of awe as we reflect upon the lives of a father and son, bound together in a darkly poetic and deeply moving tragedy.

Nicole Bilan is a comparative literature graduate, currently studying for her master’s degree at King’s College London. Stating the obvious, she’s a bookworm who’s interested in pretty much anything—longform essays or fragments of poetry, she’ll give it a try. She gravitates towards writing about identity politics and self-fashioning in text, but also loves anything with a hint of the surreal. She’s got her sights set on a Ph.D in the not-too-distant future, but in the meantime is pursuing a career in publishing. She’s usually found writing in the company of a small dog, who kindly snoozes on her legs or laptop to aid the creative process.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: