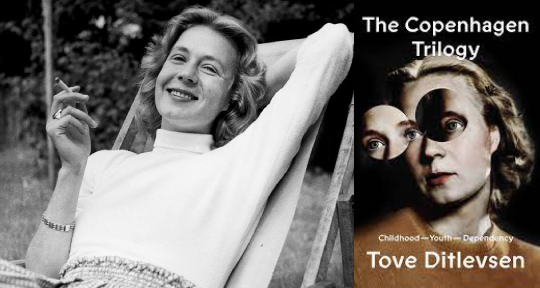

The Copenhagen Trilogy by Tove Ditlevsen, translated from the Danish by Tiina Nunnally and Michael Favala Goldman, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021

When I was a young girl, when beginnings were pure and brute in their unknowing, my mother ruled alone over the great realm of truths. There was the education in sensual matters (the fragrance of her unfettered in the mornings, porcelain spoons filled to overflow) and the introduction of worldly wonders (mittens, pinwheels, rock sugar), but mostly she was the insistence of one, axiomatic certainty: no one will ever love you the way I love you. She said it often, matter-of-factly, without any cadence of sentiment or tenderness, to comfort just as well to condemn—no one will ever love you the way your mama loves you. This line never wavered. It never tarnished. And it has stayed with me my whole life.

The memoir can be a baffling genre, and the writer’s memoir most of all. One spends their whole life under the thrall of converting subjectivity into objectivity, studying the essence of things and their multiplicity, studying the losing journey living matters embark on in order to arrive at the page—at the culmination of such a discursive, cognitive, and all-bearing life, what is left for the private language to make public?

“a whole person / is too much to take,” Tove Ditlevsen writes in her ninth volume of poems, Det runde vaerelse. Yet in her memoir, The Copenhagen Trilogy, she still commands the facts of her life with that same prolific, torrential force that has sprawled through dozens of texts, telling of madness and poverty and femininity in the various violences they enact upon a single body, all in a fastidious discernment of what can be made material by ink and paper. In the reading of this monument to a life of letters, one is left with the sense that yes—a whole person is too much to take, in the way that anything, forced to be seen with such unimpeded clarity, is.

To tell the story of a life, there is always the light shone into the intimate, unthinking crevices of origin. Before Tove Ditlevsen was a woman, she was a daughter. The excavation of memory is a conscious act; some things may rise to the surface in gasps and startles, but in Childhood—the first act of the trilogy—the author is herself grasping the glimmers of what can be told to make sense of the now. In the way of Hayden White, who said, “What is at stake is not, ‘What are the facts?’ but rather, how are the facts to be described in order to sanction one mode of explaining them rather than another.” The first fact then, is that there was a girl, and there was her mother. It is the people who know you from your first moments who hand you the legends by which the world can be deciphered, and this, as Ditlevsen goes on to tell, is the making of a tragedy.

I look up at her and understand many things at once. She is smaller than other adult women, younger than other mothers, and there’s a world outside my street that she fears. And whenever we both fear it together, she will stab me in the back.

Amongst what is largely agreed to be unforgivable are mothers who do not love their children—even worse are those who love, but do so as flawed, fragmented, and unhappy women. Through the portraits of Ditlevsen’s child-sense, one glimpses the shatterings of a mother who, in all her cruelty and neglect, sinks in the daily despair of a life dispossessed. The words of my own mother resound—no one will ever love you the way your mama loves you—and she was, of course, right; but it is not necessarily that a mother’s love is all-encompassing, or more magnanimous, or even more impassioned, but simply that it is the first love that you know, and therefore informs the love that you then bestow, and the love that the mother of The Copenhagen Trilogy manages is one full of human weakness. So it is that the above passage ends with: “. . . my heart fills with the chaos of anger, sorrow, and compassion that my mother will always awaken in me from that moment on, throughout my life.”

Were I to speak with her, I believe Tove Ditlevsen would stand—at least in part—with me in my position that poets are born, not made. As such the efflorescence of a young devotion to language marks the most immediate, epiphanic, and tortured portions of Childhood. (“Someday I’ll write down all of the words that flow through me. Someday other people will read them in a book and marvel that a girl could be a poet, after all.”) In the deprived, habitual patterns of being young and drained of wonder, it is language that comes as something of redemption. In the proceedings of familial trespasses, hesitant growings, and the volatile impositions of those that populate the joyless residences of Vesterbro, the young poet contains within her bursting mind the convictions of her fate. “Even though no one else cares for my poems, I have to write them . . .” To read Ditlevsen’s young verse here is sweet, consolatory; we know that within their immaturity, a certain glory is supine and patient. Poetics are glimpses at destiny; they indicate one’s innermost pursuits, discerns what is seen from what is looked at, and paves the path that the poet follows, in reverie.

Surely there are many routes to find one’s way to poetry, but this sense of absolution is what grasps and holds the poet to this frugal, vicious, uncompromising art. As Childhood leads into Youth, the girl finds her way into “a real poem,” the ferocity of which carries her through odd and painful jobs, odd and painful men, and still—that pervasive haunting that love, and perhaps all instances of coming up against another person, is never without the shroud of furtive, innermost darknesses. In a stunning domestic scene, Ditlevsen’s older brother, Edvin, sneaks a look at some of her poems and is taken by their loftiness into hysterics: “‘Oh God,’ he gasps and doubles up with laughter, ‘this is hilarious. You’re really full of lies . . .’” Almost immediately thereafter, however, he breaks into equally uncontrollable, equally explosive sobs. One senses that this first instance of illumination between the two—in which the raw humiliations of self are mirrored by the presence of an equal—had come about by the unusual, numinous quality of words. Words which even in the heightened elapses of fancy, in the strange conjuring of the never-seen and never-felt, can still reveal, incarnate, a truth about the one who has written them.

Divided into its triptych, The Copenhagen Trilogy maintains its conspicuous, haunting regard of time’s linearity. Having been written over the course of four years (1967 to 1971) but elapsed through a lens of decades, each section forcefully impresses the oblique illuminations of distance. Her voice remains steadfast in its gently invulnerable retelling, but the transmogrifying substances between Childhood to Dependence is striking. Where the former glints with the kaleidoscoping abstractions and détourné of memory—less concerned with documentation than it is with illustration—the latter is corporeal with urgency, as if it is the not-so-long-ago that dangles off the precipice of the mind, needing to be rescued from the irredeemable stations of forgetting.

The melodrama of one of Denmark’s most well-loved authors suffocating under horrific marital abuse and crippling opiate addiction casts a pale, opaque pallor over the text’s pages. As Ditlevsen moves through marriages, becomes a mother herself, and rises through the ranks of the Danish literati, a shot of Demerol intended to soothe the disturbances of an abortion promptly collapses the already fragile mental architecture founded upon the lucid capacities of envisioning. Quickly escalating in her addiction, Ditlevsen headrushes through unthinkable matters—marrying her dealer, having his child, undergoing an unnecessary surgical procedure that leaves her deaf in one ear—and, in a procession that is not any less sorrowful for its predictability, stops writing.

Will I ever write again? I remember that time long ago when sentences and lines of verse were always flying around my brain when the Demerol started working; but that doesn’t happen anymore.

Dependence, with its frenetic pace, its indolent need, and its trembling depictions of a woman dissolved, is a journalistic delineation of decline. In unrestrained, hurriedly punctuated lines, the sense of departure from one’s own body—one’s own life—is concurrent, urgent. There is little of the phenomenological phantasm that populate the preceding sections; she is rescuing remnants from the flood.

With the first two parts translated by Tiina Nunnally and the last by Michael Favala Goldman, the English prose honours the lilting musicality that Ditlevsen has cultivated with her poems. They are of a careful, unexacting oratory—one hears within the chiming of the words an ease of someone who knows the fascination she evokes, the grip she exerts with her medium. Even as she describes herself in the tumult of insecurity, or shame, or regret, or the horrific deluge of her addiction, in the confines of the page she is fearless, precise in her remembering, commanding in her retelling. It is, in the end, this one irreducibility that draws her back into herself.

I left the light on, and I lay there, looking at my bony white hands, and I let my fingers move as if they were typing. Then I had a clear thought for the first time in a long while. If things get really bad, I thought, I’ll call Geert Jørgensen and tell him everything. I wouldn’t do it just for the sake of my children, but also for the sake of the books that I had yet to write.

Strange that to learn about one’s life, it is not sufficient to only live; one must also wander the halls of the past, searching, opening entryways within ourselves for the past to re-enter, anew. That the narrative which forms alongside a lifetime is not simply a document of happenings, but a discourse of reconciliation, not simply testimony but a manifesto of reinvention. The sadness by which Ditlevsen regards the women who were unable to tell their stories is symptomatic of the fact that so many of them were utterly deprived of control, of any semblance of ownership over their days; the helplessness of others confirmed her own presupposition—that the only way to own one’s life is to never concede in the telling of it.

Simone Weil said, “Avoid beliefs which fill the emptiness, which sweeten the bitterness . . . for love is not consolation, it is light.” The harsh love of growing. The gnawing love of becoming. The excruciating love of freeing oneself. This is Tove Ditlevsen’s legacy—to have turned on the glare of feeling so that it may reveal. To have had this light stay on, her whole life.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: