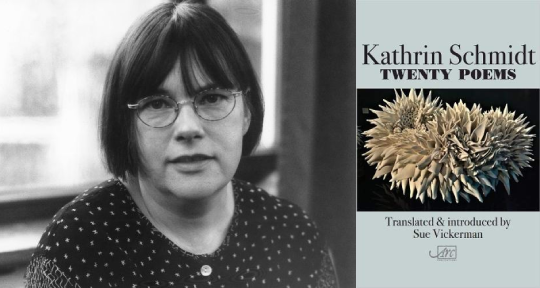

Twenty Poems by Kathrin Schmidt, translated from the German by Sue Vickerman, Arc Publications, 2020

Born in the former GDR and now of Berlin, Kathrin Schmidt is a renowned poet and novelist. Notorious in her native Germany as a competitor of Herta Müller (since beating the celebrated writer for the 2009 German Book Prize), she is a strong and serious voice of what translator Sue Vickerman terms “the left-behind east.” Schmidt, who has worked as an editor and a child psychologist, has published six poetry books and five volumes of fiction in German. A versatile author whose own interior and external experience stands at the base of her writings, Schmidt continually broaches contemporary topics, from the fall of the Berlin Wall to migration in the era of the internet, with relentless perspicacity and humor.

An excellent translator doesn’t necessarily have to be a writer, but when an exceptional translator is an exceptional writer in his or her own right, as is the case with poet-translator Sue Vickerman, the experiment takes on a new aura, advancing transcultural dialogue and culture itself. In her introduction to Kathrin Schmidt: Twenty Poems (the author’s first collection in English), Vickerman draws the reader into her own personal experience of translating Schmidt, a project she completed with obsessive attention to detail and superhuman dedication.

Vickerman’s profoundly personal engagement with Schmidt informs the translation; deeming her a “kindred spirit” of a similar age and worldview, Vickerman—deeply affected by Brexit—began translating Schmidt’s work as a creative response to the upheaval around her, finding similarities in the divided country that Germany once was and that Great Britain has recently become, the two states mirroring one another with paradigmatic shifts, ruptures with the recent pasts, and new zeitgeists. As such, “these twenty poems draw together work from five of Kathrin’s six collections published before and after Reunification (1990).” The free-verse poems, characterized by “labyrinthine nuances,” address sensitive topics without any hesitance: eroticism and the body cohabitate with the concept of a “lived history” that is both personal and national, both anecdotal and macroscopic. As such, reading this poetry hailing from East Germany raises the following questions: How are writers writing about Brexit now? How will they do so from now on?

Take, for instance, “Day of the drop dead divas,” a totem of a poem, emblematic for what Schmidt has set out to represent: an epic portrait of a decadent society, transmuting in more eccentric shades the critical urban portraits in the manner of Juvenal and T.S. Eliot. Trenchant and scathing, it is an argument of a poem with a dynamic vortex-like quality, pulling the reader down under, guided by hypnotic language: “not a single bourgeois amaryllis adorns the boulevard.” In this poem, Schmidt perceives the centrifugal city’s hum and energy: “the divas up top / want to simply speak berlin like a poem.” She demonstrates breadth and range, then moves to a concise yet enigmatic rural parable right after in the following poem, with the sense of drama shifting from social to individual as parental concern is broached anecdotally. Importantly, Vickerman notes: “published in 1987 in the GDR, the poem demonstrated how wordplay and punning had been useful devices for sidelong criticism of the régime.” This notion can be applied to every one of the poems in the collection, conferring it an additional dimension, which can be understood as subliminal for the author and subconscious for the reader.

Like Paul Celan and, on occasion, Samuel Beckett, Kathrin Schmidt excels in linguistic abstraction—thus being, on a formal level, a saliently difficult author to translate: Vickerman spent almost three year immersing herself in Schmidt’s imaginative world and making tough decisions. In one exemplification of her intricacy, Schmidt writes of “bounteous tree, / need it weather all these assaults,” of

smokes ravening plumes

billow blue

heavenwards and temptation

is baking in that oven:

the taking of bread

whereby hunger and lust

are one

Schmidt has a Dickinsonian way of plying language like a jeweler, and similarly seems to boldly dominate the reality she inhabits in an unorthodox and irreverent way: “Winter is hanging so pure out there / like a nappy. Come on, / let’s go carve our shadows in it, / cut it up for lunch.” Details serve an almost parabolic purpose for the undeniable expression of a social conscience, reinforcing poetry’s power in national crisis. In this sense, Schmidt reminds me of Romanian poet Magda Cârneci—as for both poets this grim exterior is contrasted by a rich inner life: “im still snagged on / the hitches of those years / the bitterest bits / the beautifulest,” writes Schmidt.

The reader perceives an almost spiteful intensity: Schmidt is determined to use the most searing images to jolt the reader into the reality she has been forced to live in; in this sense, she is a social poet par excellence, never censoring or softening the frightening and painful aspects that are undeniably inextricable from the pulse of real life. From an individual standpoint, self-hatred (“if you now came back / your voice would be a small island / on my heads clear-felled wasteland”) appears to be supplemented by meticulous lucidity (“i slept for months in reverse mode, / sliding into childhood”). Snippets and fragments function as ambiguous half-portraits of a cumulative experience, understood implicitly through searing images without being directly referenced: Schmidt’s “trickster” voice coexists with her opening a door prophetically to cosmic possibility and profound implications:

while the flake-fall was still light, we were happy with

the fate that hung above us on untampered-with threads

but, as these began to fray and split, our destiny on a

different shape. we became unstable, unable to stand as it

fell and fell from the sky

Noting Sue Vickerman’s abundant enthusiasm in the translator’s note, I set out to discover who Sue herself is, particularly in light of her involvement in the Poettrio Experiment—a new, interactive way of looking at both writing and translating. Vickerman is herself a writer from the north of England, the author of five books of poetry and four of fiction. Her most recent is Adventus, published by Naked Eye Publishing (an independent press in Bradford undergoing a rebrand toward world literature). Reflecting with terror on Brexit, this book of self-referential poems is informed by this specific cultural context: “I put Radio 4 on. Fusty cottage bad smell.” Not incomparable to Schmidt’s aforementioned “Day of the drop dead divas,” her work is characterized by an awareness of cadence (“the fell’s dry-stone-wall-bevelled loveliness”)—wistful but never overbearing, meticulously ominous though never obvious: a breathless and charged countdown to the rupture that has occurred, an eloquent expression of impending doom:

stacked-up rocks that go back centuries,

luscious mosses that go back millennia,

sleet, rain, sleet, now slithery heather,

now tactile lichen-laced granity crags

Gloriously polyphonic and polymorphous, the poetic narrator merges personal and national crises with an equality in deftness of form and sentiment:

uncertain hills;

a changing light that never would have worried me

before. But now, no hand is reaching out to reassure

Thus, though they come from different cultures and approaches, the two poets meet in their exigency and perspicacity, their quintessentially European writing towards a determined and defined idea. Sue’s translation of Schmidt’s short story collection, Finito. Schwanm drüber (It’s Over. Don’t Go There), will be published in late 2021 by Naked Eye Publishing. Having read one such lighthearted, profound story in advance, it seems that both writers have made evident their grassroots approach to writing about a firm reality and future. I am very eager to see the writerly and translatorial relationship between Vickerman and Schmidt develop through this exciting text, and can confirm that there are great things to come.

Andreea Iulia Scridon is a Romanian-American writer and translator. Her translation of a series of short stories by Ion D. Sîrbu, a representative of subversive writing under the communist regime, is forthcoming in 2021 with ABPress, and her co-translations with Adam J. Sorkin of the Romanian poet Traian T. Coșovei are forthcoming in 2021 with Broken Sleep Books. She has a chapbook of her own poetry forthcoming with Broken Sleep Books and a poetry book forthcoming with MadHat Press in 2022.

*****

Read more reviews on the Asymptote blog: