“Although this film is universal, I wish to dedicate the prize to all Iranians,” spoke Marjane Satrapi as she accepted the Jury Prize at the 2007 Cannes Film Festival for Persepolis. Adapted from her bestselling graphic novel of the same name, Persepolis is the autobiographical story of young Marjane as she comes of age against the backdrop of the Iranian Revolution. Although she left Iran for Europe as a teenager (briefly returning to Tehran at the age of nineteen) and has lived in France since 1993, her words clarify Iran’s continual importance to her, as well as its enduring presence throughout her work. Written in French, Persepolis is both a memoir about the challenges of growing up and finding an identity and a fierce, intelligent, and nuanced depiction of Iran following the 1979 Revolution. It is at once enlightening, wise, funny, horrific, melancholy, and profound. In the following conversation, Blog Editors Xiao Yue Shan and Sarah Moore consider this groundbreaking graphic novel, which has sold more than two million copies worldwide, and its 2007 film adaptation.

Sarah Moore (SM): Interestingly, Marjane Satrapi co-directed and co-wrote the film, so in Persepolis we can see how the author wanted to transform the drawings to animation. Satrapi recreates her own work, and she does so in a way that is loyal to the graphic novel, whilst clearly making use of what a new form can offer. Marjane is not a typical heroine. She is bold, honest, relatable, and she is blunt about the uncertainties she experienced growing up. The film transfers her to the screen with remarkable success, without losing any of her spark, humour, or complexity; Persepolis stands out for being able to narrate the political through this fierce character. It is the story of Iranian politics and life, as well as the story of a girl traversing through adolescence. Satrapi has often stated that one individual is the only universal thing—so whilst we witness the Iranian Revolution, the killing of political prisoners, and the Iran-Iraq War, we also follow Marjane as she dreams of being a prophet, goes through puberty, falls in love, has her heart broken, and suffers depression. I think Persepolis is rare in being able to move so much of the atmosphere and energy of a text into film, and one that genuinely works as a cinematic narrative as well. Of course, the plot is condensed, especially during Marjane’s time in Vienna. But the subtlety of emotion and the fullness of the characters carry through to the film, as well as the blend of humour and tragedy. What did you think of the move from book to film in a general sense?

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): There is something more automatic in the transition between graphic novel to film; in textual adaptation, a director must enforce their own visions in a discrete—albeit secondary—architecture, but the graphic novel has an established visual vocabulary. It is a transition that is made with minimal sacrifice. Still, I think there is a certain magic that is rendered between the pages of a graphic novel, in which two frames are juxtaposed by not the logic of movement or chronology, but mimics instead how a scene is pieced together in the mind—with interrupting segments of memory, reference, and unconscious categorization. The rationale of film narrative has to preserve a certain logic: the sense that something is always coming up next, much more resembling the way that biography proceeds—in the distinct knowing that a life continues.

In an interview published in Fourth Genre, Marjane Satrapi says: “When you watch a picture, a movie, you are passive. Everything is coming to you. When you are reading comics, between one frame to the other—what is happening, you have to imagine it yourself . . . It is the only medium that uses the images in this way.”

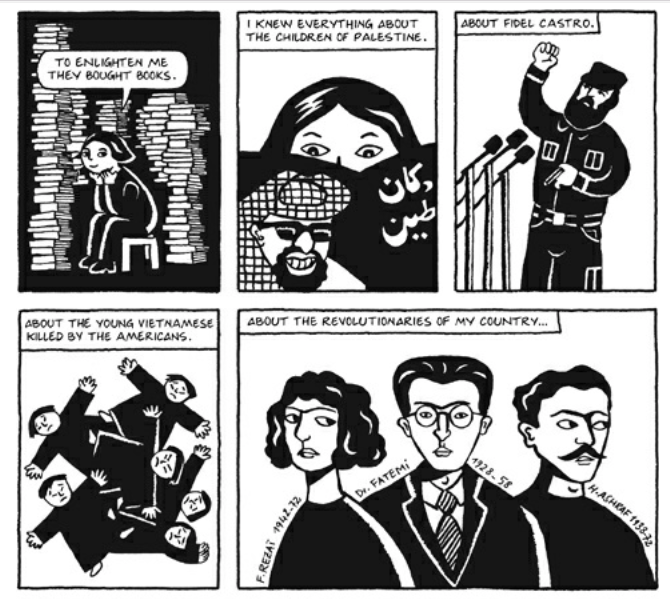

The triumph of comics lies in the immense variations available in seeing, especially when seeing becomes privy to imagining. Satrapi doesn’t make much use of shadow or dimension, relying instead on the starkness of contrast and the vivacity of drawn schematics and constructions, so the process of extending these images over three hundred-some pages is to cure reality of its bindings, to displace it into the realms of mind-space. The consistent surprise and renewal of discovery in visuality must propel the reader along. That is not to say, of course, that Satrapi’s writing is not immersive, nor that her story does not innately possess some powerful thrust, but that her images borrow from the text’s penchant for reconciling past and present, specific and general, distance and immediacy.

SM: Yes, and one of the big differences between the graphic novel and the film is the presence of colour scenes in the film, which take place in Paris-Orly airport. Marjane wears a red coat, starkly contrasting with the rest of the film and the black and white graphic novel. These scenes serve as a link between time periods and act as a “present” from which Marjane narrates the story of her life. They draw out the themes of exile and belonging from the written story. An airport is a place of transit, and by returning to Marjane alone in the terminal, we feel more strongly her sense of isolation and of being between various worlds. In the graphic novel, the airport is also an important setting. Both volumes end with emotional goodbyes at Tehran airport as Marjane first leaves her parents to go to Vienna, and then her parents and grandmother to leave for France. The film adds a final scene after this second departure. As Marjane leaves Orly airport in a taxi, the driver asks where she has come from—”Iran,” she replies, proudly and firmly. Her response recalls pivotal moments earlier in her story—in which she had lied and pretended to be French, as well as her grandmother’s insistence, “Never lose sight of your dignity. Always stay true to yourself.” I felt that the film worked more towards this resolution of acceptance and catharsis—of finally arriving and revealing a true self. Whilst present, this was less pronounced in the book, and I wonder if it also related to Satrapi’s involvement with the film, made after she had literally revealed her story through the graphic novels.

XYS: I think you’re definitely right about this, Sarah. It seems to me that this differentiation in character development (or delineation) can also be referred back to the custom expectations inherent in each artistic form. Whereas comics privilege the isolation of each moment in the long streamline of moments, the film’s insistence is towards coherence. There is a delicacy here in how each slight alteration of the content turns to embrace the traditions of its form. I do agree with you that certain attentions here can be assigned to retrospect here, however; we are, after all, bound by linearity to see ourselves as cumulative things. I really love the candor that Satrapi takes to her own depiction. She revels in her imperfections, her naiveties; there is a kindness in which she treats her portraiture that does not necessitate sympathy, but instead an assuredness that the girl there is a woman now.

We must also address that while the first volume of Persepolis was released in 2000 (with the second volume following in 2004), the film hit the public arena in 2007. By then, the world had become familiar with the phrase “axis of evil,” which George W. Bush first applied to the nations of Iran, Iraq, and North Korea in 2002, and then used unceasingly throughout his presidency. Satrapi responds to this unidimensional, villainizing interpellation by stating that it utterly reduces one to “a very abstract notion.” The scene in the film in which Marji, adjusting her veil, is eyed with suspicion by the woman sitting next to her in the airport does not exist in the book. The dignity and the grace by which the cinematic Marjane works towards her self is perhaps in response to this desire to rescue Iran from this reduction, which is merciless and—regrettably—too-often irreversible.

Speaking of colour—Satrapi has said that she had difficulty regarding the depiction violence in the comics, as the pervasive of violent imagery has rendered them platitudinous—turning the looker into what Sontag called “tourists of reality.” Her choices to absolve the images of colour, then, was a highly resolved decision to reintegrate the shock and severity back into these depictions of violence. In the panels in which prisoners are being tortured, Satrapi draws in brutal strokes a man cut into pieces, his flesh white against the black background. There is no blood, only the painful blackness between the severed segments. The unreality of this image heightens the horror by removing the reality from it, reinstating it not with immediate witness, but a forced and communal imagining. There is no medium which can accurately represent this trauma; Persepolis relies on it to say: just because you have not seen it, does not mean it did not happen.

SM: I think you’re right. Perspolis avoids colour and makes use of different techniques to portray the nature of the story being told. Stories are embedded within Marjane’s narration, which are signaled to us by a different style. For example, when recounting the history and wider political context of Iran, the graphic novel uses images with a greater scale, featuring crowds. When she moves into scenes of her imagination, this is reflected in a more dream-like, decorated style. Photos are also important in the graphic novel. The first book begins with photographs: first, an image of Marjane at the age of ten in 1980; then, a class photo. Throughout, their importance as a record of events is underscored. But all of these photos are equally drawings by Satrapi, who simultaneously presents her own images as significant records of life in Iran. In the film, what struck me most about the different narrations was the style used for the stories of Iranian history, presented like puppet shows. In a way, they are like history viewed from afar, by someone who has to learn the basics quickly. It is reminiscent of the way that history is taught to children. Satrapi has also spoken of how the animation, rather than live-action, renders the film universal. And I think the styles also demonstrate how Satrapi plays with simplicity, especially in a work with so many personally and politically heavy themes. As you said, the minimalism of the drawings and the 2D image techniques in the film accentuate the gravity of the story.

XYS: In Dana Heller’s essay on Diane DiMassa’s serialized comic Hothead Paisan: Homicidal Lesbian Terrorist, she proposes the idea that comics have an enormous potential for dissent, as the strategy of using an unassuming, playful form has the capacity to “camouflage” the strong messages of subversion by portraying them in seemingly innocuous packages. I think Satrapi’s style is very much in line with this thought, and her artistic choices very deliberate in accentuating the rawness of trauma in violent moments, the evocation of orality in retellings of passed-down history, and the dreaming underbelly of a childhood. I think with the transition between the page and the screen, there were also shifts in the intersections between narration and dialogue. In the comics, the recitative text occurs most often, hovering over the speech-bubbles in a stilled acknowledgement of telling what one has witnessed. In the film, however, this technique would have been impossible to render in faith, and thus the conversations reign, and the historic flow of time is restored. It is odd, and somewhat wonderful, to me then that it is still the silent medium that preserves and honours the voice, the stoic remembering figure.

Golnar Nabizzdeh wrote about Persepolis, “The visual domain of comics allows the other to imagine worlds and states of being through her hand. This provides a distinct contrast to the ways in which women’s lived experiences have been historically silenced.” These works are primarily ones of witness, and Satrapi repeatedly stressed that her purpose in creating these works was to stress the active importance of Iranian representation, and a resistance against the punishing simplification of enforced definitions.

SM: And with music having been so important in the graphic novel, but silenced because of the form, I loved how it could be used to great effect in the film. Of course, there is the punk and rock music from the United States that Marjane loves, but is strictly forbidden. Music is a powerful means of expression, and buying and listening to Western music runs alongside Marji’s rebellious nature and outspokenness. She refuses to give up her freedom with these acts of listening and enjoyment. In the film this can be made even more prominent: in the fantastic scene where “Eye of the Tiger” blasts while Marji gets ready in the morning, for example. Music is also used to great effect in drawing out the script’s humour. More traditional music is present, especially in the historical scenes. Such music is used behind scenes with little dialogue, but also to affect emotional response, often melancholy or nostalgia. Strangely though, in this sense, I don’t feel that the graphic novel lacks any force of emotion without this music. In the film, it is enjoyable, but not necessary.

XYS: That “Eye of the Tiger” montage killed me! It was so wonderfully done, so jubilant, so rightfully roaring; I love it when these kinds of heightened scenes feel deserved. I would agree in saying that the use of music wasn’t absolutely contingent to the film, but I thought it was applied elegantly. Another scene in which the sound stood out to me was when Marji floats up to the skies in the vision following her suicide attempt. The sounds are delicate, ethereal, and supplement the gentleness in which Satrapi gifts her autobiographical subject.

Perhaps the reason why the graphics do not seem to require the added emotional impacts of music is because the framing of the comic itself does such an apt job of pacing and providing rhythm to the reading. In addition to the large, quieter frames which capture landscape and scope, there are also thin, rapid panels—the sequence of which can resemble a heart pounding or an incoming crowd.

One thing I would like to bring up is that the language of both the text and the film is French, as opposed to Persian, which Satrapi and her immediate family presumably use to communicate with one another. The author stated that she chose to write the book in French because it is addressed to the Western sphere, towards their understanding, and as a consequence to her unflinching hand and eye, Persepolis has been banned in Iran. Satrapi has said: “A person laughing or crying means the same thing everywhere in the end.” Though a multilingual rendering would’ve proved impossible in the graphic text, I occasionally found myself wishing that the film, and its access to that multi-pronged instrument—the voice—would have approached Persian and applied it as well, in what would have surely been a manifestation equally moving to the creator as to the viewer.

SM: I think you’re absolutely right to mention the language. Satrapi is multilingual (speaking, in addition to French and Persian, English, German, Italian, and Swedish) and had a choice of which language to write in. I can’t venture into her exact reasons for writing in French but, as you say, she has spoken about her intention to engage the Western world in Iran’s history and her true experience there. To write or speak in Persian may have destroyed this intention and not made use of her position of being able to bridge the two cultures. In that sense, I don’t quite agree that the film would have benefited from incorporating Persian. Satrapi co-wrote and co-directed the film with Vincent Paronnaud, a well-known French comic book author. I think the strong French presence in the film (language, cast, production) shows how the book is (as Satrapi often notes) universal, and yet deeply personal—the two cultures are clearly important for Satrapi. And the film is, to a large extent, about exile. The French language can therefore signal nostalgia, melancholy: what was lost and what was gained in return. It’s worth also noting Persepolis‘s accomplishment in publishing and film industries that are so heavily dominated by the English language. The film was a global success and I still think it’s a great shame that the film missed out on the Best Animated Feature Oscar to Ratatouille! It’s interesting that Satrapi decided to provide English subtitles for the French version of the film and then released a second version dubbed in English. Catherine Deneuve and Chiara Mastroianni voice Marjane’s mother and teenage Marjane in both, respectively, but in the English dubbing young Marjane speaks with a heavy American accent that gradually fades as she grows older. I’ve always been unsure why a dubbed version was necessary, but given that Satrapi and Paronnaud oversaw the direction for the English dubbing (which also features a stellar cast of Sean Penn, Iggy Pop, and Gena Rowlands!), I think that an English version must have been a welcome decision for them. In every turn of its conception and adaptation, Satrapi does seem to demonstrate her desire to bridge cultures; the need to present her knowledge of Iran to as wide an audience as possible. As she said in a French interview in Les Inrockuptibles, “If I could have made this film in Persian, I wouldn’t have needed to make it.”

Sarah Moore is a British editor. Her interviews and reviews have been published in Literary Hub, Words Without Borders, Bright Lights Film Journal, and Asymptote, among others. She is blog editor at Asymptote and editorial assistant at SAGE publications. She previously ran the monthly poetry events, “Poetry in the Library,” at Shakespeare & Company bookshop.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Author of the poetry chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love. Find her at shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: