The intricate latticing of a family’s dysfunctions can provide ample material for any writer, but that is no indication that the material is easy to render in its full complexity. In our Book Club selection for January, however, we are proud to present a text that explores the peculiarities of familial relations to tremendous result. My Grandmother’s Braid, written by acclaimed author Alina Bronsky, tackles the subject(s) with equal parts biting wit and generous compassion, culminating in a subtly sensitive portrait of what happens behind the closed doors of households, and the closed minds of our loved ones.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

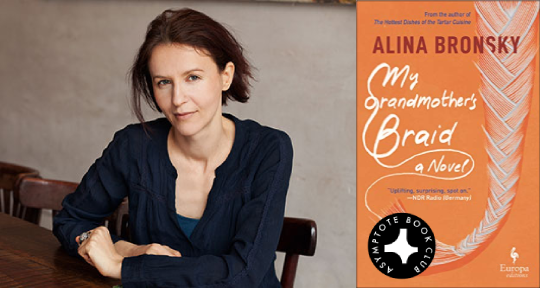

My Grandmother’s Braid by Alina Bronsky, translated from the German by Tim Mohr, Europa Editions, 2021

Over the years, I have grown weary of that infamous Tolstoy adage that “All happy families are alike; each unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” Mostly because it seems to me that the sources of our unhappiness tend to be often so ordinary (and thus far more common that we’d like to admit); evil can lack imagination, and even the worst of pains can soon turn into dull aches as we get used to almost everything. Dysfunctional families, however, are another story, and the family at the center of Alina Bronsky’s My Grandmother’s Braid, translated by Tim Mohr, takes the idea of dysfunctional to a whole new level. Despite its relative slimness, this book takes the reader on a journey with so many twists and turns that I kept staring at the pages in disbelief.

At the age of six, our narrator Max immigrates from the Soviet Union to Germany with his maternal grandparents, taking shelter in a refugee home. The verb “immigrate” is technically correct, although there is a sense that Max and his grandfather, Tschingis, didn’t immigrate as much as they were dragged to the unnamed German town where the story takes place by Max’s grandmother, Margarita Ivanova, or Margo.

Margo is the driving force behind this story and almost everything that happens in Max’s life (and not only Max’s). Worried that Max’s health is too precarious for Russia, she exploits the family’s threadbare Jewish heritage to gain refugee status. Once in Germany, she seems to suffer from what can potentially be described as Munchausen syndrome by proxy: she is certain that Max is too fragile to live as a normal child would—that he is afflicted by a number of inexplicable maladies. She hauls Max from doctor to doctor, all of whom continually refuse her diagnosis as she grows ever more certain of their incompetence. She feeds Max only steamed vegetables and unseasoned barley and oats and refuses to let him go play with other children. When Max starts first grade, she insists on being seated at the back of his classroom and interrupting his lessons with her often-wrong advice on how to solve his math assignments. The dullness of Max’s school life eventually becomes too much for her, and it is only when Margo grows bored that Max is able to gain a little bit of freedom and agency. And it is here that the narrative begins to speed up, and the years slide by to the point where reader loses track of how much time has passed.

Central to My Grandmother’s Braid are also two other Russian immigrants: Nina, a piano teacher, and her daughter, Vera. We learn from the beginning that Max’s grandfather falls in love with Nina. The two begin an affair known to everyone but Margo, until Nina falls pregnant. There is a mounting tension to the story as the reader becomes aware of this affair and grows as terrified of Margo as Max and the rest of the characters are. You wait for the implosion that is certain to happen when Margo learns of the affair, expecting everything to fall into pieces and unable to quite imagine where the story will go from there. How can it all stay together?

The much-awaited implosion, however, never comes. Margo takes everything in stride, congratulates, and immediately takes the baby under her care. There is no escaping the home she creates, nor the haphazard family she commands at her will, although Nina tries hard to leave it all behind. The following exchange between Vera and Max encapsulates the unorthodox dynamics of their hybrid family:

“Sometimes I think my mother is married to your grandmother,” Vera whispered in my ear.

“No, they hate each other,” I said, as if that would rule out marriage.

I was afraid while writing that I was giving too much of the plot away, but I think there is not really a danger of too many spoilers here. First, because the reader can anticipate the truth behind the mysteries and even some of the twists—though Bronsky’s skill as a writer means that even the anticipated twists can shock and hurt the reader. But the spoilers should not disturb potential readers because My Grandmother’s Braid is above all a character study, and a skewed one at that. We see Margo through Max’s eyes and yes, of course, his grandmother is a difficult character to like. She is proud, prejudiced, secretive, and steamrolls everyone and everything in her path to get what she wants. She seems also incapable of saying a good word to anyone.

There is much to be said for subjectivity, but Margo’s actions speak for themselves. Yet, there is also a vein of sadness and misery throbbing beneath every facet of story. We as readers have to reckon with the fact that there is much we don’t know and much we will never learn, because Max will never learn it. Her constant fear that Max will die, her endeavors to keep him safe, eventually begin to sound less like a pathological issue and more the result of a tragic past. Margo had given up a career as a ballet dancer to marry Tschingis, who then betrays her with a younger woman, but still manages to open a successful dance studio on her own while in Germany. In the novel’s tenderest of moments, when Max comes back from school, he begins to linger in the stairways of their apartment building, listening to his grandmother—who would never admit to such moments of pleasure for pleasure’s sake—play an old piano hesitantly.

Just as Max’s childhood is shaped by his grandmother’s menacing and extravagant fairytales, My Grandmother’s Braid is written in a style that seems at turns facetious and tragic; one finds themselves snorting with laughter during the most inappropriate moments. And just like Margo herself, this book is funny, maddening, and surprisingly sentimental and compassionate. It seems incredible to flip through the one hundred and fifty or so pages that comprise this novel and realize how much there is still to talk about, how many pivotal moments to savor and analyze. It is a book about complicated characters and families, a book that takes every tragedy seemingly in stride but hides the most important poignant moments in fleeting gestures and phrases. A balancing act that requires your full attention even as you rush through the pages to find out what happens. Where does life—or Margo—take these characters?

Barbara Halla is an Assistant Editor for Asymptote, where she has covered Albanian and French literature and the Booker International Prize. She works as a translator and independent researcher, focusing in particular on discovering and promoting the works of contemporary and classic Albanian women writers. Barbara holds a BA in History from Harvard and has lived in Cambridge, Paris, and Tirana.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: