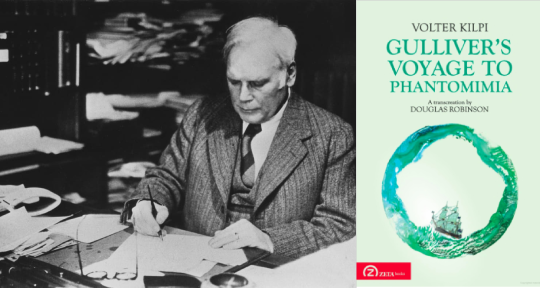

Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia by Volter Kilpi, in a transcreation from the Finnish by Douglas Robinson, Zeta Books, 2020

All reference sources on Volter Kilpi (1874–1939), Finland’s most renowned prose fiction experimentalist from the early twentieth century, will unanimously cite his novel In the Parlour at Alastalo (1933)—with its nine hundred pages conveying just about six hours of story time—as the writer’s main masterpiece. Difficult reading in the original, this modernist tour de force is also deemed untranslatable, with only a Swedish version available to a non-Finnish audience. As a result, Kilpi’s fame does not traverse lingual borders easily, and his reputation as James Joyce’s literary peer is established by proxy: most of us would just take a Finnish professor’s word for it. The arrival of Douglas Robinson’s English “transcreation” of Kilpi’s posthumously published last novel, Gulliver’s Voyage to Phantomimia (1944), indicates a seminal challenge to this status quo.

The original Kilpi novel pretends to be the Finnish-language publication of an English manuscript that a Finnish librarian (presumably, Kilpi himself) happens to discover among old manuscripts in stock, “caked with dust.” It turns out to be Lemuel Gulliver’s own account of the fifth round of his exciting travels, which Kilpi “translates” for his local readership’s convenience. Kilpi began working on the novel in 1938 and wrote twenty-five chapters before suffering a debilitating stroke, but articulated an approximation of his plans for the remainder. Taking up this playful design of a sequel to Jonathan Swift’s 1727 classic, Robinson then develops and intensifies it: not only does he translate the Kilpi text into a stylized version of Swiftian English, with eighteenth century spellings and phrasings to make it resemble the “original” Gulliver manuscript, but he also supplies it with a bunch of metafictional “Introductory Texts” and an ending—another seventeen chapters, an intratextual sequel to Kilpi’s intertextual one.

The way Robinson finishes the novel stretches matters far enough to incorporate a satirized Donald Trump-like character into a futuristic 1938 London, where Kilpi’s Gullliver finds himself having traveled through time. Robinson sandwiches eras and places as radically as Kilpi most likely would not, unless the Finnish ascetic high art author were a twenti-first century maximalist jocular scribe. This transcreation of the Kilpi transcends all the limits and borders the Finnish novel initially appears to set, but does so openly (as the Introductory Texts never tire of revealing) and consistently—by relocating Kilpi’s reservedly satirical experiments, aborted at the author’s death, into the jungle of infinitely recursive postmodern jouissance.

The book opens with an “Editor’s Foreword,” where the fictionalized Doug Robinson, a translation theorist and English professor based in Hong Kong, relates the twisty circumstances of his taking hold of Swift’s handwritten Gulliver’s Fifth Voyage at a Yale University library. Prior to his discovery, the manuscript seems to have served as a major inspiration for the 1914 Vorticist Manifesto, the source text for Kilpi’s unfinished 1938 Finnish translation, and as an artefact temporarily kept on the planet Venus. We are soon to grasp that the person responsible for the lost-and-found English classic’s extraterrestrial trip is quite multi-faced: he is the telepathic voice of Ezra Pound and the librarian inaugurating Robinson’s possession of the manuscript at Yale, as well as one of Gulliver’s companions in the voyage and the fictional publisher of the entire book we are reading. Since Kilpi’s Phantomimia is reached by a two-hundred-year leap from 1738 to 1938 via the “Polar Vortex” à la Edgar Allan Poe’s 1841 short story “A Descent into the Maelström,” such omnipresence of the character Ethel Cartwright is motivated by his excellent command of time machinery.

The Foreword is followed by another four sections of Part I: the “random notes toward a vorticist manifesto” proving that even the name of Pound’s modernist movement alludes to the vortex in the newly acquired Swift, Volter Kilpi’s “Translator’s Introduction” to his Gulliverin matka Fantomimian mantereelle, a fictitious Finnish professor’s outraged report of Robinson’s unacceptable English “travesty” of Kilpi, and the “Publisher’s Postscript” by Ethel Cartwright. Kilpi’s reuse of the found manuscript fictional device in “Translator’s Introduction” to his 1938 novel is thus encased amidst fictitious paratexts cross-referring to each other circularly—sometimes viciously so: in his “Reader’s Report,” for instance, Prof. Julius Nyrkki attacks the indebtedness of Robinson’s narrative embedding of the Kilpi to the analogous structure in Vladimir Nabokov’s Pale Fire based on Robinson’s passing remark in “Editor’s Preface,” but the “Preface” includes a response to Nyrkki’s critique. Which of the two is written earlier, and who is responding to whom? In footnote 11 to Nyrkki’s “Reader’s Report,” the “editor” ([Ed.]) exclaims, “What is this paragraph, if not a response to my footnotes?” right before the paradox is resolved: as the same footnote continues to say on the author’s and translator’s (“[Au./Tr.]”) behalf, that author-translator (but not “editor”) “wrote this ‘reader’s report’” himself, which the “publisher” reconfirms in his “Postscript”.

Kilpi’s narrative of Gulliver’s Voyage translated into English and completed by Robinson entails the book’s larger Part II. The transition from Kilpi to Robinson is made explicit: “The part left untranslated into Finnish at his death by Volter Kilpi” starts from Chapter XI of Book Two and goes to the end of Book Three. We must not forget that the fictional editor’s heavily compromised claim ascribes the entire thing to Swift, more or less. Insofar as our actual authors—Kilpi and Robinson—never say that they are authors, hiding behind Gulliver and Swift, respectively, they mimic their common prequel: Swift too speaks through Gulliver the narrator and Gulliver’s editor/publisher Sympson. Had not the name “Cartwright” figured in Kilpi (but not Swift) before Robinson, we would be encouraged to suspect that American actress Nancy Cartwright—the voice of Bart Simpson in The Simpsons—is part of this Robinsonian cruise (excuse my Defoe). The sheer joy of such far-reaching free bonding of eras, languages, and genders is explained by “Robinson” to “Nyrkki,” whom Robinson calls ze in lieu of he: to the imaginary Finnish professor’s rhetorical wondering what Robinson gains by his transformative but disrespectful treatment of Kilpi’s original, Robinson footnotes, “what I gain is giggles.”

In the nautical Book One (“In the Polar Current”), Gulliver relates his voyage to the North Pole aboard his drinking pal Cartwright’s ship, the Swallow Bird. The vessel gets caught in the polar vortex, descending it for months, with just four survivors left of the crew. In Book Two (“In Phantomimia”), Cartwright, his 15-year-old son Ethel, Gulliver, and Higgins walk away from their ice-stuck ship to meet a British polar expedition of 1938 and have some hilarious exchanges about clothes and other cultural differences, after which powerful “Flying Machines” take them to London, where many strange things amaze them. Robinson’s part of the story starts with the four characters invited to see King Dick the Stiff in the Royal Palace; the King is an arrogant sadist, paranoid about the expected Venusian overtake of his powers—a problem he confronts with abusive legislation and murderous violence. Ethel, who adapts to the future much more readily than the adults, manages to fly them away from Phantomimia and back into the time vortex, hoping to arrive in 1738, but Gulliver’s Bible that they rope down from the aeroplane into the water to retrace their route seems to throw them too far into the past. In Book Three (“In the Conquest of Canaan”), the travelers are separated and placed among the characters of the King James Bible (James also being the name by which the Yale librarian introduces himself to Doug Robinson in “Editor’s Foreword”). Gulliver and his fellows witness some genocidal atrocities reported in the Old Testament and die terrible deaths alongside hundreds of others. However, Cartwright Junior befriended Venusians during their brief stay in Phantomimia and mastered the art of time travel, so that all eventually return to the eighteenth century, where we leave Gulliver at his home gate.

Even though Kilpi’s modernist Finnish would sometimes feel strange to his native readers, he does not imitate 18th century language: after all, today’s editions of Swift “translate” his outdated English into comprehensible contemporary diction. Robinson’s capitalization of nouns and artificial aging of grammar and vocabulary in his translation is thus part of his overall meta-narrative framing of the Kilpi. To readers who know other Robinson translations, such as his recent take on Brothers Seven by Alexis Kivi, or his translation theories (Robinson is an internationally acclaimed translation scholar, who has authored dozens of academic books in iconoclastic translation studies)—it comes as no surprise. It is so easy to identify Robinson’s own voice when Nyrkki attacks him for failing to perform “the translator’s humble prostration before the unattainable brilliance of the original” that one needn’t receive a direct indication that Robinson wrote Nyrkki himself: it is the transcreator’s irony that Nyrkki proclaims his values by negating them. Robinson’s project is performative: think of contemporary productions of classical drama redressing it in twenty-first century costumes and moving it to this day’s settings. What Robinson does as a literary stage director, he also does as a translator: His performance of the Kilpi novel amplifies whatever subtle overtones there are about the author’s style as well. Take alliterations: when Gulliver reads Cartwright’s irritated glance at him, Kilpi only alliterates the last two words of Gulliver’s interpretation, “merkilliseksi mitannut,” literally “measured as meaningful,” but Robinson starts lobbing m-words thirteen words from the end:

Cartwright, for his Part, bestow’d upon me a Glance, that was nigh unto a Sneer: As if to say, there, you hear now what they make of your Tall Tales; but he kept mum; misdoubting from his moonish Mop, he meted this Mome’s mellsome Miching Meed-less.

Translatory meekness is not for this translator, whose Kilpi speaks so modern by speaking obsolete.

To “gain a giggle” while getting to know a text by a key twentieth century Finnish writer and reencountering one’s favorite eignteenth century English character is most certainly a bargain. Those of us who will go for it and like it may also expect the show to go on: rumor has it, Robinson is currently translating Kilpi’s magnum opus, In the Parlour at Alastalo.

Ivan Delazari teaches Comparative Literature at HSE University in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 2014-2018, he was a PhD Fellow and part-time lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University, where he explored contemporary American prose and taught English academic writing and twenty-first-century fiction. He is the author of Musical Stimulacra: Literary Narrative and the Urge to Listen (Routledge, 2021), a book about experiencing music by way of reading novels.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: