“All Romanians are born poets,” goes a local saying, but far too few are published in English. Among their faithful champions, award-winning translator Adam Sorkin stands out: while some of us forwent productivity in favor of survival this year, he managed to put out a whopping three Romanian poetry translations. In times of collective confinement, they fittingly tackle the self’s relationship to space: the city, the countryside, the foreign land. They hone in on different forms of love and fear, too, from the romantic to the maternal to the religious—the love and fear of God. Beyond these and other commonalities, however, they differ in structure and style: the first is an emotional bildungsroman, the second an epic, the third a hymn of sorts. This formal range attests to Sorkin’s chops, which Assistant Editor Andreea Scridon is only too happy to extol.

It’s always contentious to name someone the best translator of a language, a claim that is perhaps more trouble than it’s worth. I, for one, tend to shy away from such absolutisms, but Adam Sorkin gives me second thoughts. Undeniably, he’s at the top of his game, having published over sixty books of Romanian poetry in English translation (even in the year of the plague, he’s managed to publish several).

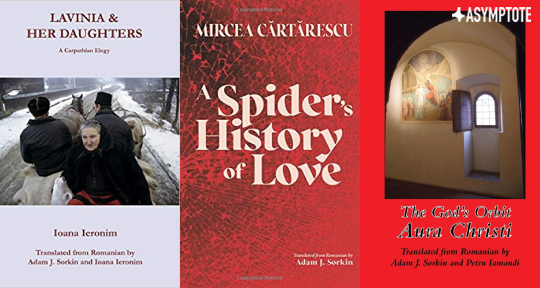

Of the three most recent ones—Mircea Cărtărescu’s A Spider’s History of Love, Ioana Ieronim’s Lavinia and Her Daughters, and Aura Christi’s The God’s Orbit—I must admit I’ve only read the first in the original (among contemporary authors, Cărtărescu is a firm favorite of mine, so the stakes were especially high). All three, however, merit attention.

I have no interest in writing a sycophantic or fawning piece; in fact, I would be embarrassed to be so generous with praise if I didn’t feel that Sorkin’s corpus demonstrated exceptional verve and dedication—two especially valuable traits in a sometimes thankless publishing industry that doesn’t necessarily have an interest in promoting a minor language. To put it simply, having worked with Sorkin myself, I knew he wouldn’t disappoint.

A Spider’s History of Love was published by New Meridian Arts in July, making it the first of three Cărtărescu books to come out in English around this time (Solenoid, translated by Sean Cotter, will be published by Deep Vellum in 2022, and Nostalgia, translated by Julian Semilian, is forthcoming from Penguin in 2021). The book’s title is Sorkin’s doing, a phrase he took from a poem included in the volume, which encompasses selections from multiple collections; these are curated into three sections, entitled “Once I Had . . . ,” “Bebop Baby,” and “Prisoner of Myself.”

Considered cumulatively, these poems do not seem to represent an overarching epic odyssey in the same obvious way that Ioana Ieronim’s Lavinia and Cărtărescu’s own Levantul do; rather, they resemble an emotional bildungsroman with porous boundaries, entirely dictated by the inner life of the poetic narrator as he bends, with force and delicacy, the world to his perception, and not vice versa.

In “Once I Had . . .” and “Bebop Baby,” the microcosm of the poet’s Bucharest serves as the stage for various amorous pursuits. With obvious erudition, indicated by winks to his forerunners in Romanian literary history, Cărtărescu combines Romantic and Levantine elements with communist shabbiness. Thus, contemporary banality, even poverty, are seen through an euphoric eye and become savoury for those who understand how to look the right way, thanks to the poet’s almost rabid attention to detail:

. . . and deep down in the digestive tract I could spy

death herself.

I saw her leaning against the iron fence of the TB hospital next to the police headquarters

stopping a kid on the sidewalk to send him to fetch a newspaper or a fresh bun

and I saw her shopping for bread and newspapers in the pinkest, most incomparable

xxxxxxxxxsunset.

(“Love Poem”)

Everything becomes effervescent and iridescent for this narrator, a master of the art of sublimation, who seems to be eternally in love. His are confessional narrative poems—a form which suits the sentimental experience, with its varied shades and seasons. Long as they may be, they read quickly, engaging with reality and avoiding excessive abstraction. The rhyme is ingenious thanks to both the author and the translator (“. . . the evening / deposited thin sheets of lapis lazuli / the parked cars seemed folded from tinfoil and smelled of patchouli”; “. . . and your figure reminds me so little of aesop / that I wrote you a bebop”).

Often, Bucharest appears a live chameleonic organism (“who are you, Cișmigiu Gardens, smoking like a blue snare, / what color is your life, intercontinental hotel of velvet?”), which makes us wonder: is this ode of love in fact a tribute to the city, the constant element that can truly be possessed by its inhabitant, or to a row of alluring but unidentified women, mysterious and unknowable? The poetic narrator seems trapped under a spell, and more often than not, the woman in question turns out to be an illusion, a dream of desire:

God, how your skirt hung stiff and shredded into scraps while you were standing in front

xxxxxxxxxof the Unirea Department Store

and your skin crumbled into pieces like old paper

your flesh fell in crusty flakes like plaster

your skeleton disintegrated: the maxillae, phalanges, tarsi, vertebrae

dissolved into dust as after a fever

and of the store there remained a few steel uprights,

a handful of aluminium hangers, some haberdashery . . .

(“History of an Ocean”)

The vision of this universe is distinctly curated and cleanly defined, perhaps disqualifying the poet’s style from being utterly postmodern—as he himself says in a poem entitled “Eye to Eye”: “I harbor my own imaginary.” At any rate, he creates a decidedly cosmic atmosphere, as if the reader were watching a tiny Mircea in Bucharest via a telescope from the moon.

A sense of impending doom, of accepted despair, begins to creep in towards the book’s third section, as the poet matures: the final poems read as an elegy for the person who wrote the earlier ones, and they consider the chronic unhappiness of the sensitive individual by retaining the fusion of what is at once repulsive and magnificent (“now a million diseases adorn me / with a bride’s gossamer veil”). At the same time, there’s a shift towards a more sincere and perhaps less artificial space, indicating a change in direction when the poet’s daughter is born. “The Occident,” featured at the end of the book, is an extraordinary poem, both a travelogue and a swansong:

the West opened my eyes but knocked my head against the lintel

and brought me down low.

I leave to others my life until today.

let others believe in what I believed.

let others love what I loved.

I no longer can.

no longer can. no longer can.

This ending suggests the great pause to come—indeed, Cărtărescu has, with the occasion of the pandemic, published his first poetry book in about thirty years.

*

Of the three titles in question, Ioana Ieronim’s Lavinia and Her Daughters (Cervena Barva Press) is the most “high-concept”: it adheres to exploring a focused experience and formally reads as a narrative or epic poem. “A synthesis of poetry and prose,” Sorkin writes in the foreword, “is what makes the peak of creative writing today, if there were a God to measure creative gold at all.” He adds that “the systematic totalitarian policy of post-World War II Romanian communism to subvert and alter the fabric, the values, and the rhythms of life as it used to be is at the core of the work, along with depiction of age-old beliefs and communal relations that were being destroyed.” This grants special significance to the fact that the original Romanian version of the book was first published in 1984, a few years before the revolution.

Ieronim writes with boldness, and what we could deem “emotional faithfulness,” about Romanian peasants—their stoicism in dealing with death, and their profound connection to the space around them. She also tackles how rapports develop in the ecosystem of a remote and rural community. Thus, the book is a delicate tribute to both the titular woman’s condition and traditional life at large:

He looks down to Lavinia—frail, city-like in her black patent-leather slippers.

“‘Cause hay, you don’t put it right, it heats up like corn,” he adds, “it can even catch fire, phew, God preserve us”—and before his eyes, his Maria’s feet appear to him, so broad they don’t fit even her big hand-made country shoes—and so in winter you see her rushing to the well to fetch water, or to the cattle: slapping against the snow, her feet beet-red.

(“Works, Days and the Sliding of the Ground”)

Beyond the story of Lavinia, these are testimonies (in the form of poetry, nodding to oral traditions of storytelling) of various people—particularly women, each with her own feelings and problems. Some of these are tragedies created by communism, which tried to obliterate everything in its wake, but others are universal dramas—heartbreak, a sickly chid, or the brutality of aging (“Late at night, in the light of the gas lamp, the old woman can see her own hands, / her skin like parchment over the bones and her big wooden veins. / She stares at them. A stranger’s hands”).

Yet these other characters still are, of course, secondary to the mother figure embodied by Lavinia, and the ode to motherhood that the book ultimately is:

Lavinia has thought a thousand times about that moment of separation

pressed smooth by clear reasons.

But the bridges had fallen down, fallen down. In her tortured soul, the earth tore loose

from the waters.

The sublunary leaves, newly budded, hesitate between nonexistence and birth

nests of moist tender green born on the old foliage.

(“Prologue”)

The natural environment of this space is more vibrant than others, but ghosts of great historic drama, dead and alive, imbue the atmosphere in complex strata. An air of freshness is discernible; images are intense. The poems’ form mirrors the passage of time, thick and ample like a blooming apple tree—an image that recurs throughout.

*

The God’s Orbit, by Aura Christi, was published by Mica Press in October and co-translated by Adam Sorkin and Petru Iamandi, a versatile translator of Romanian into English and vice versa. Judging from the biography presented in the book, it seems quite clear that Christi’s being an ethnic Romanian born in the Republic of Moldova has directly influenced her work across genres, which is often focused around notions of foreign occupation and exile. The book does make this apparent, though never in a dogmatic way: it acknowledges and explores the topic repeatedly, but it goes beyond it too.

These are poems of self-discovery, self-definition, and often self-consolation, operating on a lyrical, religious, and metaphysical plane. “Tell me, God, whose transient flesh am I?” Christi asks in “Someone Else’s House”; the book is definitely a Credo, a discovery of God inside one’s own amorphous yet vivid universe:

I’m alive.

I smell of paper

and black currants. Like the dolphins in the water

I glide from one kind of waiting to another;

what do they call the never-ending one,

I wonder?

(“The Ferryman of Souls”)

God is a constant preoccupation, but He grows more vivid and less abstract the more fearfully He is portrayed, much like a child’s fear of darkness (“How can I live, oh, God, with Your light, / if it strikes my entire being like a hatchet?”).

Christi’s poetic gaze is sensual and ethereal at the same time (“Fragments of apocalypse deliriously crushed / under the eyelashes, like nutmeats between your teeth”). It is also, however, undoubtedly depressive—both Bacovia’s and Dostoevsky’s influences are apparent. In fact, Christi seems to be under the spell of Russian literature, and interacts with its characters in the poems “Porfiry Petrovitch’s Lesson” and “The Psalm of Light,” the latter featuring Prince Myshkin.

The poems are also often rather abstract syntheses of intense psychological experiences and terrible internal processes, punctuated by gothic images. They reach brave levels of interiority by relating phobias, weaknesses, and dreams that many might find impossible to utter, all marked by profound loneliness:

Just do something about this fear!

Look at it, it comes in flocks, God, like the late crows

on the threshold of winters. I listen to the caverns murmur inside me

and I know only that I no longer understand anything,

and you, after you showed yourself to me, won’t come back.

(“Fear is a Sign that the God breathes”)

The external world is refracted through the prism of the poetic narrator’s feelings at any given moment, and thus the title tells us what to expect: a deeply hymnic poetry that riffs off of what figures like Blake and Dickinson have done—a difficult genre to master. Christi engages with the Bible, but also with paganism and with Ancient Greece, referring to Achaens, Zeus, Apollo, and Pegasus with a compellingly solemn sense of drama.

Her poems have plump shapes on the page, and they are usually relatively short. Sorkin favors clean, aerodynamic translations—something that the Romanian language, with its longer words and more grammatically convoluted structures, doesn’t necessarily facilitate. He doesn’t shy away from what initially seems to be somewhat prosaic language, which doesn’t mean it is devoid of musicality.

As a speaker of Romanian, I enjoyed the inclusion of the titular poem in the original, which made it apparent that Christi’s work is difficult to translate. And while every translator chooses different words, the trick is to make it look easy. In this, as in so much else, Sorkin succeeds.

Andreea Iulia Scridon is a Romanian-American writer and translator. She studied Comparative Literature at King’s College London and Creative Writing at the University of Oxford. She is assistant editor at Asymptote Journal, fiction editor at the Oxford Review of Books, contributing editor at E Ratio Poetry, and an occasional assessor for English PEN’s PEN Translates programme. Her translation of Ion D. Sîrbu’s short stories is forthcoming in 2021 with ABPress.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: