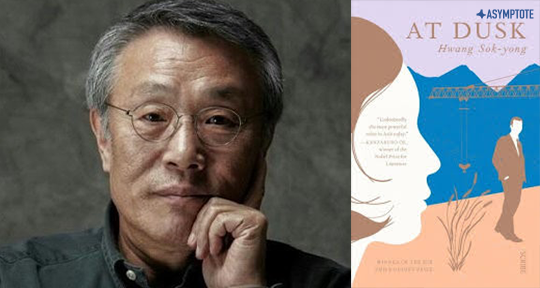

Watered Foxtails: A review of Hwang Sok-yong’s At Dusk (tr. Sora Kim-Russell)

Set against the backdrop of South Korea’s rapid rise in the second half of the twentieth century, At Dusk follows the divergent fates of two children from the same slum, Moon Hollow. One (Park Minwoo) manages to fight his way out of poverty; the other (Cha Soona) never leaves it behind. Committed to our current technologized reality, novelist Hwang Sok-yong pieces together his protagonists’ past and present through text messages, phone calls, emails, and video fragments. At one point, pierced with sudden yearning for a childhood the memories of which he has long suppressed, Park even does a Google search of “urban redevelopment.” It is supposed to be a sign of Park’s prominence and success as an architect that such a generic term readily yields photos of his own large-scale residential redevelopment projects that paved the way for South Korea’s ruthless modernization. (Just as compelling if much subtler is the suggestion that Moon Hollow isn’t searchable on the Internet directly by name—so utterly has it been obliterated.) Now, fifty years after he has left Moon Hollow and at the dusk of his life, Park is haunted by what he has bulldozed to get to where he is today.

Points of view alternate in Hwang’s brilliantly executed novella nesting story within story—each with the perfect amount of exposition topped with vivid specificity—and whose translation in Sora Kim-Russell’s poised English was longlisted for the International Booker Prize in 2019. A less imaginative writer would have made Cha narrator along with Park; but, instead of Park’s crush, Hwang arranges for another female character (Jung Woohee) to take the reins of even-numbered chapters. A young struggling artist who barely makes ends meet by working night shifts in a convenience store when not putting up plays, the milieu Jung occupies is worlds away from the other narrator Park’s.

At first, the two narrative strands that make up At Dusk’s rags-to-not-quite-riches story seem unrelated. It’s only when a fourth pivotal character, Black Shirt, a male co-worker, appears in Jung’s life that pieces of the puzzle start to shift into place. Though it is also hinted that Black Shirt may be to Jung what Cha is to Park (i.e., true love realized too late), Black Shirt’s character serves at least two plot-related functions and one discursive one: First, as a former construction worker, he has witnessed the kind of suffering that guilt-ridden Park refuses to stick around for—through him, then, Hwang gives voice to the powerless. (In a stunning scene that must have scarred Black Shirt forever, a teenager protests his family’s forced eviction by charging headfirst into the still-swinging metal arms of an excavator that has come to demolish their home.) Secondly, Black Shirt is the one who introduces his mother Cha to Jung, whereafter a friendship develops, and Jung, learning about Park, decides to continue Cha’s love story first by showing up at Park’s public talk with a note containing Cha’s phone number and then by impersonating Cha in her emails to Park after Cha dies (i.e., essentially staging a drama of her own making offstage). Finally, in Black Shirt’s own tragic demise (his lifeless body is found with that of other strangers after an online suicide pact), Hwang shows how the crisis of meaning is not confined to those who led inhumane modernization efforts—the rot has spread to the generation subsequent to Park’s. Though her career as a playwright has only ever been an uphill slog despite winning a New Playwright Award, at least Jung can tell Black Shirt what all her hardship is for; Black Shirt, on the other hand, is hard pressed to say why he is hustling so hard to stay alive. Just like Park at the end of the book, Black Shirt is lost too.

Life’s meaning, then, seems to lie in Jung’s transgression (of which the very practice of literature in an unforgiving capitalistic society is surely part). When the clicking into place of disparate narratives finally occurs—which it does all the more satisfyingly for being very late, the unassuming 29-year-old is exposed as the true agent of this novella. Even if she has to resort to catfishing Park, she is determined to play out Cha’s unfinished love story. By so doing, she materializes an audience for only one of the many neglected voices that have been swept under the rug of history. The following passage, narrated in a moment of supernatural lucidity by a shaken Jung as she leaves the deceased Cha’s apartment for the final time, seems to hold not only the secret to Jung’s intervention but a metaphor for literature itself:

As I was carrying the last of her items out of the apartment, I noticed a flowerpot in the corridor outside her front door. It was overgrown with foxtails. They were yellowed and starting to wither, as if they’d been neglected for a while. I told myself she couldn’t have possibly planted them on purpose, that the seeds must have been blown into the pot by the wind and sprouted there. But at the same time, someone must have watered them for them to grow that lush in the first place.

This concludes our four-part spotlight on Korean literature. We would like to thank LTI Korea for making it possible.

Lee Yew Leong is the founder and editor-in-chief of Asymptote. Based in Taipei, he works as a freelance editor and translator of contemporary Taiwanese literature. Recipient of the James Assatly Memorial Prize for Fiction (Brown University), he has written for The New York Times, among others, and served as one of the judges for PEN International’s 2016 New Voices Award.

Read more from the Asymptote blog: