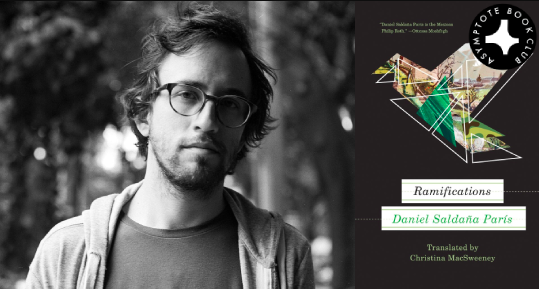

It is perhaps fitting (though regrettable) that our October Book Club announcement has been somewhat delayed: Daniel Saldaña París’s Ramifications is all about holdups. Via Christina MacSweeney’s seamless translation, the acclaimed Bogotá39 writer gives us a counter-formative tale that is both masterfully constructed and poignantly penned. In it, he exposes existential and political conservatism without dealing cheap blows, and introduces readers everywhere to a profoundly relatable narrative voice.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD15 per book; once you’re a member, you can join the online discussion on our Facebook page!

Ramifications by Daniel Saldaña París, translated from the Spanish by Christina MacSweeney, Coffee House Press, 2020

Ramifications opens with a brilliant gambit; within a handful of paragraphs, it both sets up and crushes the prospect of a bildungsroman. A grown narrator feeds us the near-requisite opening, the painful loss at a much-too-tender age: in 1994 his mother, Teresa, flees their home in Mexico City, leaving ten-year-old him and teenage sister Mariana in the care of an oblivious father. Just a few lines later, though, we get a sharp taste of his current predicament—far from being the seasoned, thriving type mandated by the genre after years of fruitful struggles, he defines himself as “an adult who never leaves his bed.”

The rest of the novel artfully explores the tension between the classic formative tale and its antithesis. Parts one and two delve into Teresa’s disappearance and her young son’s attempts to make sense of it, culminating in what could have been an archetypal “journey of self-discovery”—he tries to follow her to Chiapas, where she’s run off to join the budding zapatista movement. Part three, by contrast, hones in on the trip’s bland aftermath, both instant and deferred. It’s not as tidy as that, of course (the narrator jumps back and forth in time), but there’s an overarchingly grim shift from promise to flop. It’s made all the starker by a series of deliciously clever winks from the author: the protagonist’s childhood neighborhood and school are literally called “Education” (“Educación” and “Paideia,” respectively), and he’s thirty-three at the time of writing—an age that, for culturally Catholic audiences at least, can’t help but trigger unfavorable comparisons.

A disclaimer, lest readers think I’ve spoiled the plot: the novel doesn’t ride on events. It is, at its core, an absorbing character study, driven not just by voice (more on that later) but by a deeply original theme: (a)symmetry as a curb on growth.

On the most basic level, there’s our protagonist’s fetish with the art of paper-folding, which appears to give name to the book:

I used to . . . pull leaves off the shrubs. I’d fold each leaf down the middle . . . Then I’d attempt to extract the petiole and the midrib (I liked calling the stalk of the leaf the “petiole” and the central axis, from which the veins branch out or ramify, the “midrib”) . . . as a form of training for origami.

This seemingly casual pastime takes on urgent meaning after his mother’s abandonment—which is, in itself, a starkly asymmetric act, breaking the balance of a gender-split family of four. He, too, is destabilized: “someone had, without warning, expelled me from paradise . . . into the dirty, violent realm of history.”

Origami becomes a desperate bid to salvage that paradise lost—the safety, sanity, and above all, symmetry of life prior to orphanhood, when days were “divided along the same axis, like a square piece of paper retaining the memory of its previous folds.” For a while, he swears that if he jots down his deepest wants (chief among them, Teresa’s return) and shapes them into perfect figures, they’ll have “magical effects” and come to pass. His cranes and pagodas are, alas, hopelessly flawed, and he eventually tires of these botched incantations. His efforts to bring his mother back continue, however: the imitation of her features and demeanor, he reckons as a teen, might make her “return to [his] life via the oblique route of DNA.” He gets into the habit of talking like her, or growing and wearing his hair like she used to; likewise, he pores over the details of his face hoping to find hers (much to his chagrin, he inherits his father’s voice, looks, and “brusque, uncouth manner” instead).

Let down by these earlier tactics, a now-adult protagonist flirts with others. He thinks of boarding the same bus he took twenty-three years ago in search of Teresa so “the ramifications of that night . . . [might] be obliterated,” her absence reversed through the “ritual repetition” of his pilgrimage. Most crucially, though, he decides to pen his story; convinced that recalling an event simultaneously distorts it, he records his memories of his mother in order to settle them—that is, to stop himself from having to recall and distort them in the future, thus preserving her essence as faithfully as possible.

His stabs at magic, mimicry, remakes, and manuscripts all ride on the most basic form of symmetry: the one-to-one mapping of paper halves, of a self to another, of the future to the past, of remembrance to reality. But what seem like harmless gestures meant to soften his loss lead to a second, more pernicious kind of symmetry—invariance under change. The narrator claims Teresa’s departure has “hollowed him out” and “eroded his essentially feeble adult normality”; these are the ramifications he’s been trying to dodge by bringing her back in some way. In fact, however, his quest for restoration has unleashed them, irrevocably stunting his development.

Such is the heartrending joke at the center of the book, and to make matters worse, he’s unaware of it: he “pit[ies] that boy who compensated for a painful . . . situation by adopting strange behaviors” and is “angry . . . at that version of [himself] that ha[s] ceased to exist.” We, however, know that it hasn’t, and we can’t help but pity the grown-up instead (Saldaña París exploits dramatic irony to great effect). His anti-coming-of-age tale takes on powerful cautionary overtones: there’s no reclaiming childhood’s paradise after its loss, no point in clinging to the memory of its folds; only history, with its violent twists and turns, enables growth.

Another mark of the bildungsroman: the hero starts out at odds with society, but he gradually accepts its norms and is welcomed into its ranks; this is, indeed, a large part of his journey, yet the author again turns it on its head. Our protagonist remains an outcast—and perhaps it’s for the best, since the mores he grows up with have little formative potential. This time, the issue lies with asymmetry.

Every social structure, from the simplest to the broadest, is wildly unbalanced. As a child, he believes that god prefers him to all others, with his mother and then-friend Guillermo trailing close behind; later, however, when word spreads that Teresa might be a callous terrorist, Guillermo shuns him at school, hitting “the peak of his popularity” and demoting him to “the marginality of a pariah” in one fell swoop. Asymmetries are equally present at home: while god might favor him, his mother does not (she seems fonder of his sister), and his parents’ marriage suffers from obvious differences in taste, intellect, and manner. These local dynamics serve to illustrate broader inequities—notably, the rampant machismo at the heart and loins of Mexican society, and the military’s abuse of the general population. The two are jointly, vividly depicted in a bone-chilling episode during our character’s trip to Chiapas, when his bus is pulled over by the army and he’s asked to step out for a random check. With him is seat neighbor Mariconchi, who has kindly lent him a shawl:

“How old is the little girl?” The soldier in charge of the searches had a nasal twang. “Eleven,” Mariconchi improvised, “and he’s a boy not a girl.” . . . The soldier gave a coarse, rather dissolute laugh. . . . “Wow, so he was born a fairy. Right down to the shawl!” Then he laughed again . . . [and] crouched down so that his face was on a level with mine . . . Mariconchi sensed danger and tried to move me away from the soldier, hiding me behind her back. The soldier straightened up and slapped her lightly, more to sow the seeds of fear than to inflict pain.

The world he’s meant to take his cues from, then, is just as stuck in time as he is. It is to the author’s great credit that its failings aren’t caricatured. In fact, whenever they’re flat-out denounced by the narrator, his judgment is tacitly questioned. Saldaña París understands that exposure is much more damning than verdict; in this, too, he proves a deeply intelligent writer.

I’d hate to give the impression that his brilliance is merely formal, though, riding on the bold subversion of a literary genre—not that that isn’t plenty, but I promised I’d come back to voice. For the sake of patterns (which, like the protagonist, I’m rather fond of), I’ll couch it in terms of yet another kind of symmetry: the beauty that sprouts from balanced proportions. The novel elegantly straddles slang and lyricism, heartache and humor, young candor and adult nuance, yielding prose that is nothing short of exquisite. Translator Christina MacSweeney, too, pulls a spectacular balancing act: she paints a picture of modern Mexico that captures its vibrant shades without laying on an ounce of undue foreignness. This is crucial because, while firmly rooted in a time and place, our antihero’s plight is universal—much more so, perhaps, than we’d like to admit.

Josefina Massot was born and lives in Buenos Aires, Argentina. She studied philosophy at Stanford University and worked for Cabinet Magazine and Lapham’s Quarterly in New York City, where she later served as a foreign correspondent for the Argentine newspapers La Nueva and Perfil. She is currently a freelance writer, editor, and translator, as well as a blog editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: