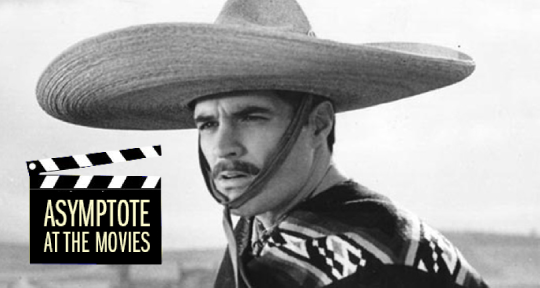

Today, on Día de Muertos, Asymptote is resurrecting Asymptote at the Movies, our column on world literature and their cinematic adaptations. In a marvellously topical fusion, we’re returning with a discussion on Juan Rulfo’s beloved and widely acclaimed Pedro Páramo, and the film of the same name directed by Carlos Velo, who dared to take this complex and mystifying text to the screen.

John Gavin, the American actor who portrayed Don Pedro in the film, likened Rulfo’s novel to Don Quixote, The Divine Comedy, or Goethe’s Faust. What those books are to Spain, Italy, and Germany, Pedro Páramo is to Mexico. It’s a declaration that would seem hyperbolic if it weren’t corroborated by so many other literary masters and critics. In her preface to Margaret Sayers Peden’s translation of the novel, Susan Sontag declared the novella “one of the masterpieces of twentieth-century world literature.” Borges declared it one of the greatest texts ever written in any language. In the following conversation, Assistant Editor Edwin Alanís-García and Blog Editor Xiao Yue Shan dive into the myriad thrills that arise between this pivotal work, and its strange and brilliant cinematic counterpart.

Edwin Alanís-García (EAG): It’s a tradition to watch Pedro Páramo on Día de Muertos. I’m not sure how or when this tradition started, but I liken it to how airing It’s a Wonderful Life is a perennial custom at Christmas. To be clear, I don’t mean that Día de Muertos is simply another holiday. It might be unjust to even regard it as a holiday; perhaps ritual or ceremony is more apt. However we label it, it’s one of Mexico’s most sacred and revered traditions, perhaps even more so than Christmas or Independence Day. A defiant celebration (literally, it’s a party for the dead) of the ubiquity of death, Día de Muertos acts as a sobering reminder that the only guarantee in life is that it ends. At the same time, it’s a festival to remember and honor the dead, especially our ancestors and those we have loved and lost. On this day, it’s said that the spirits of the dead can travel to our world, hence the importance of ofrendas, ritual displays where gifts are offered to the dead to welcome them home.

In a very concrete way, these sentiments permeate Juan Rulfo’s novel and Carlos Velo’s film: the realm of the dead and the realm of the living are constantly woven together throughout the story. We start with Juan Preciado at his mother’s deathbed, vowing to fulfill her dying wish. His mother’s voice takes him to a literal ghost town in search of his father, Pedro Páramo. Through the testimonies of the living and the dead (and it’s sometimes difficult to tell the two apart) we’re treated to flashbacks of a once thriving town and the tyrannical legacy of our titular villain.

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): Cultural commemorations and reconciliations of death seem to be mirrored across the world. In China, during a day of early springtime (a varying date on the Chinese calendar), we observe the Qingming Festival—heading to the graves of our ancestors to sweep and tidy up the grounds, burn incense and paper money, pay tribute. It is—in the same vein as Day of the Dead—an acknowledgement of the steep and synchronous passage between the realms we experience, and all the others we are offered only brief glimpses at.

Something I thought about was that—when sorting through the wreckages of a national trauma, there tends to be a reprise of narratives that amalgamate death and spirituality with day-to-day life. Day of the Dead, and what it means to Mexico, bring to mind a section of Robert Bolaño’s vividly wandering long poem, “The Neochileans”:

To the Virgin Lands

Of Latin America:

A hinterland of specters

And ghosts.

Our home

Positioned within the geometry

Of impossible crimes.

“Holidays” of remembrance are communal methods for managing the irresolution of death; when the abrupt disappearances of lives become a ceaseless tide, acceptance of its pervasion does not equate to understanding. Reading and watching Pedro Páramo brought to mind firstly the human impulse to fight against and disprove the terrifying concept of permanence. Death, our only pedestrian encounter with the eternal, is something that feels instinctually wrong for both its ineradicability and inevitability—perhaps because we have nothing to measure it up against, no certain qualifiers or records, a complete void of comparability. The persistence of ghosts, and spirits, and their continual autonomy and humanity, then, is an automatic salve for the mystifying absolution of death, and Pedro Páramo is such a brilliant dissolution of permanence, an astonishing textual disprovement of linearity and the limits of our living experience. I often find that cultures that incorporate spirituality more seamlessly into their daily philosophies are also generations that have suffered formidable violence. Along this vein of thinking, there are some who say that writing this book was Juan Rulfo’s way of protesting the failed promises of the Mexican Revolution. What do you think?

EAG: The political frame you’re suggesting is a fascinating and very apt way to approach Pedro Páramo. The time of the revolution and the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz marked a progression towards logical positivism, so certain teleological elements of Indigenous and Catholic conceptions of mortality were explicitly challenged. In Mexico, both ancient and modern views of death emphasized life as continuous with death, as being a cycle of rebirth (either into a Christian Heaven or a corporeal underworld of the Mexica). But these views just didn’t hold up any longer to “educated” and modernized lives—it could no longer “explain” or soothe the pain of mortality. In The Labyrinth of Solitude, Octavio Paz devotes an entire chapter to Día de Muertos, and stresses the cosmological and metaphysical view held by ancient Mexican philosophers that our lives are just another natural fact of the world, beyond our control—that our lives and bodies don’t truly belong to us. By contrast, the Christian focus on the self (how we “own” ourselves via personal responsibility and our relationship to God) created a new moral dimension that was ripe for social and economic exploitation, and at the same time continued this pacifying view of death promulgated in a more deterministic way by Indigenous philosophers. There was a confrontation with death that was absent during modern and post-modern (including positivistic) conversations about mortality—perhaps they were deemed by the elite of the Díaz regime as no longer “necessary”? But this disavowal of death could not apply to the poor, those forced to face death as something quotidian and at the whims of the powerful—the elite and wealthy could (literally) afford to see death as an aberration.

The promises of Díaz to modernize Mexico did succeed to some degree regarding reforms in education and separation of Church and state, but the exploitation of the poor (especially indigenous Mexicans) did not abate and were made far worse under his dictatorship, hence the indigenous uprising of revolutionaries like Zapata. The subsequent betrayal and murder of Zapata by his own allies was perhaps a precursor to the lasting government corruption that would persist in the Revolution’s aftermath—the rise of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) in Mexica, which held dictatorial power in Mexico for generations after the Revolution. For all the good the party did in terms of legislation (better labor conditions, rights for women), the sources of the Revolution’s discontent were not addressed, and were eventually made worse—something that Rulfo was no doubt addressing in the 1950s, a time when social unrest was continuing to foment against the PRI, which would soon lead to the Mexican Dirty War of the 1960s and ’70s. That Rulfo was addressing the failures of the Revolution to bring about genuine change to the suffering of the poor does seem most resonant in the character of Don Pedro. The tyrannical landowner was the quintessential antagonist of the Revolution, the one who used the government to suppress worker uprisings and claims on Indigenous lands, but the other antagonist (at least until the rise of liberation theology in the 1960s and ’70s) was the Catholic Church. We see this with the corruption of Father Renterí who defends Don Pedro and the soul of his evil son, Miguel, simply because they could pay for last rites, while the virtuous poor are left without blessings and so cannot be given Christian burials. At every level, Rulfo appears to uncover and expose the forces that oppress the marginalized of Mexico—women, the poor, the Indigenous—partially by treating them as eternal voices in the ghost town of Comala. They provide testimony to Juan Preciado from beyond the realm of the living.

XYS: With this continuously elaborating and propagating lineage of national trauma, I’m reminded of Walter Benjamin’s Angel of History, who is forced to face the past, and therefore towards an event that never ceases to throw chaos and tumult into the present. Yet, despite this awareness, he remains helpless, for he is being swept towards the future by an indomitably strong wind—that of progress. Writers take on many roles in this fragmented and multi-dimensional framework of history, but Rulfo has accomplished, with a graceful subtlety, a fiction that gives voice to the very real ghosts of his country’s brutal hierarchies. After all, in Pedro Páramo, it is only the dead that speak; the living are the ones who are relegated to voicelessness.

Speaking of voice, one of Rulfo’s most evocative and consistent literary devices here is the echo, containing within its fractured nature our referential, refracted, and broken present. Though this book presents more challenges to the filmmaker than most, Carlos Velo was most effective in his adaptation when evoking this same device in a variety of manifestations—cutting to the next scene while the voiceover from the previous continues, leaving a character’s face completely shrouded in darkness as he/she is speaking, applying a soft and wavering reverb, layering an equally voluminous music atop the dialogue . . . The constant irregularity between voice and vision is a brilliant application of distorting perception for the sake of defamiliarization: insinuating strangeness without being obvious.

When reading the book, I found myself having to constantly reorient myself around the book’s mutative reasoning, and one of the most challenging aspects of this was following the identities of the very many speakers. The voice-heavy, polyphonous nature, though common in both mediums, had very different tonal denouements. Watching the film, the shifting role of speaker and listener, and their hybridity, was obviously less of an issue of comprehension, and I was therefore much more willing to surrender to the cinematic pursuit of plot trajectory! Did you have a similar sense of distinction when going between the two formats?

EAG: Yes, absolutely. And it’s a testament to the strengths and limitations to these respective narrative artforms. One thing that fascinates me about the story is that it’s really not clear that everyone is a ghost. There’s ambiguity about certain characters over whether they’re physically present or not. But this ambiguity is much more explicit in the novel, whereas the film must rely on extratextual techniques, such as a sound and lighting, to suggest what is present (alive) and what is past (dead). Benjamin’s Angel of History is a brilliant example of what I think Rulfo was striving for thematically—that the sins of the past are always present. They’re echoes that become the noise of today’s world, nearly indistinguishable from living noise. A damage that is not reparable, only witness-able. The film version seems to expand upon this textual theme. In the times I’ve seen this film, I never before thought of the echoes in such a way—that’s a brilliant observation and an extraordinary detail on Velo’s part. I heard the echoes as an emptiness, but you’re absolutely right—they are, more importantly, a statement of time, how history is like an album on repeat. It’s a technique that—if it’s apt for me to say so—translates the sentiments and confusion of the novel into something more concrete. A limitation of film might actually demonstrate a limitation of text.

It’s interesting that the story is nearly identical between the novel and the film adaptation, though the plot has notable (and intentional) differences. The script writers (which included Carlos Fuentes—the film was a huge cultural project for Mexico) seemed to juggle the fragmentary structure of the novel (which I think we see as a textual influence on something like Cortázar’s Hopscotch) with the linear conventions of cinematic narratives. The film was still at the end of Mexico’s Golden Age of Cinema, an era where Mexico’s great films were both critically and commercially successful, so many of the traditional masterpieces of Mexican film did also rely upon a popular appeal that might be hindered by too many postmodern innovations.

The film is still very weird and ahead of its time, as demonstrated by several of the audio techniques you mentioned, which have now become standard in film. But it’s not as weird as the book. That flouting of logic which Rulfo was so good at, e.g., that dizzying and unsettling scene where Bartolomé lowers Susana into the mine, and she finds a man’s skeleton at the very spot where Bartolomé would eventually die, the implication being Bartolomé was somehow dead and alive at the same time. Though it’s since become a horror trope, this creepy detail doesn’t appear in the film, and it would’ve been rather difficult to include it. But it also would’ve been, perhaps, too much of a deviation in audience expectations of cinematic narrative for a mainstream blockbuster, at least at the time. I remember my mother said she and her sister went to see the film because it had received so much acclaim when it was released, and their reactions were pretty much what the hell did I just watch? In considering such reactions, do you think there are other literary tendencies that just fundamentally don’t carry over well into film?

XYS: Most definitely! I felt that one of the most conspicuous absences was the exclusion of “establishing shots”—which in textual equivalence was Rulfo’s utility of allusive poetry and slight Dionysian ornament in constructing his visual compendium—lines that denote not only presence, but also time’s passing and stasis. There were so many sentences that felt at odds with their surroundings in the most magical sense of delineation, brief elements of aestheticism: “still air shattered by the flight of doves flapping their wings as if pulling themselves free of the day.” Because the text is so driven by dialogue, these occasional breathing places of sensitive noticing are necessary to ground the various and reorienting POVs with an earthly, astute awareness of place: “The air carries the sound of the clear water escaping the stone and falling into the storage urn.” This steadfast and objective lyricism—which does not suggest so much as it abstracts—is rendered nearly non-existent on screen, which barely maintains a single unpopulated frame.

Velo’s preoccupation with human figures is perhaps necessary to mimic the singular logic of the novella, which is, as you say, an ambiguous procession of hearsay, memory, and illusion. After all, human continuity is much easier to follow in a film, which must maintain a chronological integrity (at least in the sense that one presumably is watching once through, without rewinding or fast-forwarding). Yet, I found the lack of an environmental anchor jarring; the camera is so insistently captivated by expressions and movements that it creates a rushed sensation of being jostled from mind to mind. One feels this claustrophobia palpably when Velo does finally impact a full or long shot, relieving the viewer of the close-up’s melodrama.

Throughout the film, one rarely see a character entering or exiting, nor is afforded a visual contemplation of the objects that Rulfo senses with such delicacy—instead, we are mostly enforced into the immediate action of the scene. It’s an interesting method of cultivating the nonlinearity of the novella, but perhaps also underscores its inadaptability. Physicality is something that cinema, as opposed to literature, has much more immediate access to, but because space is conceptualized as overall discontinuous and adrift by Rulfo, film’s normal treatment of space is not sufficient for the vertiginous Pedro Páramo. So it is that Velo must formulate the same disquiet and chaotic disruption with existent architectural elements, and while some scenes did so strikingly (Juan Preciado coming to meet with Damiana Cisneros in a stunning composition of chiaroscuro, for example), the staging of these conceptual, alternative spaces were, I feel, undermined.

You gave exact language to the uncanniness between the two mediums when you brought up how the story remains intact, but the plot is varied. One of the most notable differences, for me, was the scene of Juan Preciado’s death. Where Rulfo enshrouds it between immediacy and recall, Velo heightens its drama. At the exact moment of his life’s end, the image on-screen clouds—we are suddenly deprived of finality’s reproduction; Velo conjures vastness by way of obscurity, accentuating the object of darkness as a space of infinite potentiality.

Darkness is the opportunity of dreams to overtake the flawed rationale of our limited observations—as Borges said, “. . . night is pleasing to us because, like memory, it erases idle details.” Though Velo urges Juan Preciado’s death into something of a climax, he preserves the integrity of the Rulfo’s tenets. With dimming tricks borrowed from the night, he discreetly communicates death’s immaterialism; how the transition between the living and the dead is—in this world—minute and indistinguishable.

When Juan describes his death in the book, he uses the word “forever” with some incredulity:

Not a breath. I had to suck in the same air I exhaled, cupping it in my hands before it escaped. I felt it, in and out, less each time . . . until it was so thin it slipped through my fingers forever.

I mean, forever.

There is a communion between author and director here. Both know that they are working within the human ways of organization, which rests atop a far more indeterminate and unapproachable schema of the universe. Yet, both continue to revel in the ways their respective arts at once abide by and reinvent the terms of our existence, channelling and interrogating something as maddening as “forever.”

EAG: I’m glad you mentioned chiaroscuro because there’s so much credit due to the film’s brilliant cinematographer, Gabriel Figueroa, for orchestrating many of these iconic shots. One scene that’s particularly striking is when Juan Preciado is searching for Doña Eduviges through a dilapidated corridor. No one is on screen aside from Juan, yet the way shadows shift around the protagonist adds a sense of unsettling motion, accentuated by the fact the hallway is filled with disembodied echoes. The book relies more on cerebral moments of horror, moments that unsettle because they disturb our logic and understanding of reality, whereas the film takes full advantage of horror conventions (there are even a few jump scares in Juan’s scenes). Every time I’ve read the book, I know it’s supposed to be night when Juan arrives, but I don’t get that same sense of horror the film explicitly employs through lighting.

Perhaps this visual dynamic is another way in which the text doesn’t, and perhaps can’t, translate into film. Take certain transitions between past and present. Like you said, in the book there is no equivalent of an “establishing shot,” no setting the scene—we’re just thrown into a new block of text. And the film tries to do the same by eschewing these shots, but it feels jarring; there are jumps between scenes that are so sudden that it makes me feel as though there were some editing mistake on the cutting floor. In cinema of the era, there’s often a gradual fade out into the next scene. In Pedro Páramo, there’s no voiceover transition or fade out. This is almost an assault on the eyes, being thrown from a painfully bright and violent past into a dark, almost pitch, present full of ghosts. And when we finally get a wide, extended shot at the very end as Don Pedro dies with his ruined, barren land in the background, it’s like the visual direction must end there. No more jump between past and present is possible. The novel ends: “Dio un golpe seco contra la tierra y se fue desmoronando como si fuera un montón de piedras.” Don Pedro crumbles, collapses, like a pile of rocks… the ruthless tyrant dies, and so does the world around him.

Edwin Alanís-García is a writer, philosopher, and cultural critic. They’re the author of the chapbook Galería (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019) and their poetry has appeared in The Acentos Review, The Kenyon Review, [PANK], Peripheries, Tupelo Quarterly, and elsewhere. They’re an assistant editor for Asymptote, where they curate and edit Translation Tuesdays for the Asymptote blog. A graduate of NYU’s Creative Writing Program and the Harvard Divinity School, they divide their time between small-town Illinois and small-town Nuevo León.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor born in Dongying, China and living in Tokyo, Japan. Her chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, won the Frontier Poetry Chapbook Prize and was published in 2019. Her website is shellyshan.com.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: