Paranoid Wonder: A review of Yi Sang’s Selected Works (tr. Don Mee Choi, Jack Jung, Joyelle McSweeney, and Sawako Nakayasu)

Paranoid. Labyrinthine. Uncanny. Secretive. This is how a Korean literature enthusiast might describe the works of Yi Sang (1910-1937) before words eventually fail them. They might then offer up details of his life: that Yi lived during the Japanese occupation, that he trained as an architect, that his pen name sounds like Korean for strange or ideal, that he succumbed to tuberculosis in Tokyo after a period of incarceration for the crime of being futei senjin–a “lawless Korean.” When you hear about Yi Sang for the first time, there is something intoxicating about the reverential air, the residual awe, the mourning over what might have been. Everyone mentions how he died so young.

With the release of Yi Sang: Selected Works (Wave Books, 2020), English-language readers can chart their own journeys of paranoid wonder. The volume boasts over 200 pages of translated poetry, essays, and fiction, organized into four sections. Jack Jung tackles the Korean-language poems and essays; Sawako Nakayasu covers the Japanese language poetry; Don Mee Choi and Joyelle McSweeney collaborate over his fiction. But there is more to this division of labor than boundaries of language and genre. The volume includes essays from the translators, who speak in voices at once scholarly and personal, urgent and elegiac.

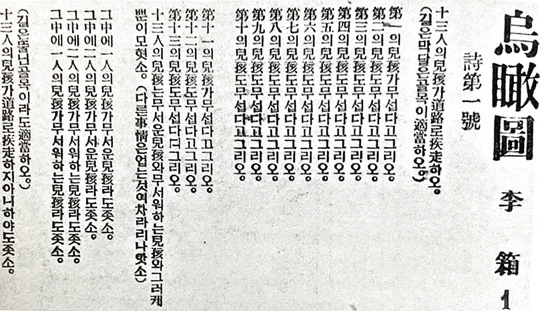

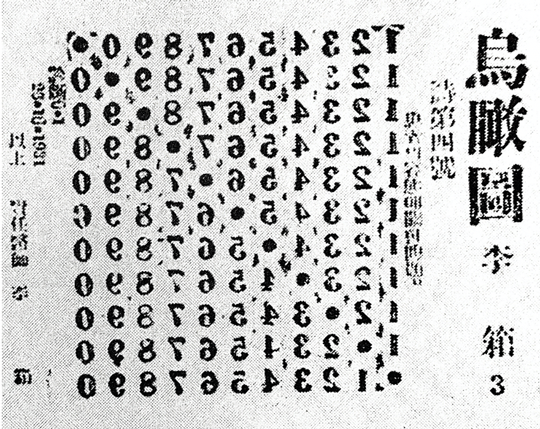

Selected Works acts as a sourcebook of images too, crucial for appreciating Yi Sang who was also a talented illustrator and artist. Much would be lost if we did not take into account the visual dimensions of his work, the unsettling emotions they were meant to evoke. Below are reproductions of “Crow’s Eye View” Poems No. 1 and No. 4, originally published in Chosun Central Daily in 1934:

Poem No. 1

For twenty-first century readers accustomed to eye-popping colors and sleek lines, the prickly black script and claustrophobic spacing may induce dread or ghoulish foreboding. Even if we can’t read the scripts in the original, we may detect lines of relentless repetition moving from right to left. We may in fact discern something presciently code-like, resembling the glittering digital rain in The Matrix.

Turning to Jung’s translation, we find our unease mirrored in the text:

The 1st child says it is scary.

The 2nd child says it is scary.

The 3rd child says it is scary.

The 4th child says it is scary.

[…]

Despite its opacity, “Poem No. 1” seems intended as colonial critique. This is suggested by the title itself, where the Sinograph for “bird” (鳥) has been changed to “crow” (烏). Notice the subtraction of a single stroke, which led many to think it was an overlooked typographic error. By turning an innocuous term “bird’s eye view” into a visuality of death, Yi Sang transforms a perspective of painterly vision into the optics of colonial domination. Reading it today, one can’t help but wonder what bleak beauty Yi Sang would’ve wrought in this age of drone strikes.

Poem No. 4

“Poem No. 4” appears to be a chart of sorts. Jung’s translation reads, “Problem concerning the patient’s face,” followed by a set of inverted numbers with dots running diagonally from top left to bottom right. It concludes, “Diagnosis by primary doctor Yi Sang.” Thoroughly flummoxed, we may forget about it until seventy pages later, when we see a reproduction of a similar poem in Japanese. Though Nakayasu handles the first line differently (“Problem concerning the condition of a certain patient”), the original lines across Japanese and Korean are virtually the same, most crucially the date of diagnosis (October 26, 1931). What could this mean? The only major difference across the Japanese and Korean versions is whether or not the numbers are inverted. The same diagnosis is made on the same day by the same doctor. One in Japanese. One in Korean. Each a mirror image of the other[1].

These are just a few of many other instances in which the image of the mirror looms large:

Poem No. 7: “Two clean mirrors faced one another and circled each other as the world revolved and rotated thirty times.”

Poem No. 8: “We apply liquid silver to the mirror from our side of reality, until the liquid silver permeates over to the other side.”

Poem No. 15: “I am in a room with no mirror. Of course, the me-inside-the mirror has gone out right now. I shudder in fear of him.”

The colonial psychic split across the Japan-Korea axis was just one of several fissures found in Yi Sang’s life and works. There is the split across city versus countryside (as seen in “A Journey into the Mountain Village” and “Ennui”), modernity versus tradition (as seen in “A Letter to My Sister”), and perhaps the most fundamental of all: translation versus original. It is said that a barmaid once pointed to Yi Sang’s facial hair and accused him of copying D. H. Lawrence, to which he supposedly replied, “D. H. Lawrence is copying me.” For many Korean writers of his generation, the problem of modernity was the problem of vying for contemporaneity while beleaguered by a sense of belatedness. The performative overturning of this vector of influence is quintessential Yi Sang.

Some encountering Yi Sang today may feel the burden of a different form of belatedness–the worry that reading his works in translation over a century after Yi’s birth puts us irretrievably beyond authentic contact. What this perspective neglects is that his works were forged in the colonial crucible of translation; this interminable sense of incompleteness, corruption, fissure, and self-betrayal was the condition of possibility for his modernist technique. For Yi–and maybe the lesson applies to us too–there is no such thing as immaculate conception in literature. (“I sleep on a cold bed, damp from embracing my crime.”)

Herein lies the greatest virtue of Selected Works. It demonstrates how the legacy of a poet is always in the process of becoming, as their works are woven into new historical and socio-linguistic sites. This is most potently felt in Don Mee Choi’s personal essay “Yi Sang’s House.” As a translator, Choi is not satisfied to remain invisible or disembodied. Her own complicated history with the Korean language is touchingly laid bare by including her father’s “photocopied pages of meticulous notes, each character numbers and explained” to help Choi decipher the Sino-Korean vocabulary in the original. She also spells out the mirroring contexts of Japanese and American empires.

For Yi Sang and my father, Japanese was their colonial language as English is a colonial language for me. We did not choose it; it chose us, historically, and that’s the nature of a colonial language…Yi Sang’s use of foreign words signals homesickness, a state of perpetual colonial exile. I am self-trained, but well trained, nevertheless, in detecting homesickness.

Opening ourselves to this poet, we may find ourselves not only reflected–even in the distorted mirror of English–but also diagnosed. “In my dream I am late. I am sentenced to death,” Yi wrote towards the end of Poem No. 15, the last installment of his “Crow’s Eye View” series before it was discontinued. “It is a great crime to seal up two humans who cannot even shake hands.”

[1] This insight comes from a footnote in Walter K. Lew’s “Jean Cocteau in the Looking Glass: A Homotextual Reading of Yi Sang’s Mirror Poems.” The article was part of a 79-page portfolio on Yi Sang, published in Muae: A Journal of Transcultural Production (1995), which included translations of Yi’s fiction, essays, poetry, accompanied by lavish photographs and writing by South Korean and U.S. scholars. Selected Works expands on these important earlier attempts to introduce Yi’s outsize impact in Korean literary history while forging new connections.

Jae Won Edward Chung is a writer, translator, and scholar based in New Jersey. He studied philosophy at Swarthmore College and Korean literature at Columbia University. He has contributed to Journal of Asian Studies, Boston Review, Asia Literary Review, and Apogee. He currently works as an assistant professor at Rutgers University. Visit him at jwechung.com.

Read more from the Asymptote blog: