Singapore’s unique multiculturalism is perhaps indicative of the world to come, an encouraging nod towards our evolving ideas of language’s forms and mutations. Just as in poetry, in which the writer is constantly mining a new idiolect from amongst the terra firma of the established vernacular, the current constraints that keep one language from colouring another are dissipating in the multilingual mindset, manifesting in a great intrigue of literary structure. This mobility of speech and its patterns—at times revolutionary, at times bewildering—is exemplified by the scrupulous and guileful poetics of award-winning Singaporean writer (and previous Asymptote contributor) Hamid Roslan, whose work simultaneously juggles and revolts against the visual, the semantic, and the syntactical. In the following essay, our editor-at-large for Singapore, Shawn Hoo, sets out on the discursive cartography charted by Hamid’s new collection, parsetreeforestfire, and finds under its myriad constructions a symphony of linguistic manipulation and play.

In 1950, within the pages of the University of Malaya’s student journal, The New Cauldron, a young Wang Gungwu pens an idealistic editorial entitled “The Way to Nationhood”—a text now regarded as a significant articulation of linguistic modernism on the peninsula hewn tightly to the dream of nationalism. He writes:

A Malayan language will arise out of the contributions these communities will make to the linguistic melting pot. The emerging language will then have to wait for a literary genius who will give it a voice and a soul, a service which Dante performed for the Italian language.

Engmalchin (a portmanteau of English, Malay, and Chinese) was the language and movement advocated by Wang and his fellow multilingual, English-educated classmates to carry the voice of poetry in post-war British Malaya, and to summon a Malayan consciousness. For this linguistic cauldron to be wrought, he had hoped for the major ethnic communities to “throw up from their native or imported civilisations the material for a new synthesis [. . .] infused with the stuff of European poetry and bound firmly in the English language.” Wang tested out this aesthetic vision in his debut, Pulse (1950); eight years later, he declared Engmalchin a failure. A new poetic idiom was premature without cultural or political independence, or as he writes, “[When] the Malayans appear, there will be Malayan poetry.” Malaya’s first dream of linguistic modernism was shattered temporarily, then permanently, when by 1965, Malaya had fragmented into what is now Malaysia and Singapore.

On the Singaporean end of the peninsula, Engmalchin’s legacy has morphed and survived as Singlish—the creole tongue mixing English, Malay, Chinese, Hokkien, Teochew, Tamil, and other languages—which in turn has found its place in Singapore poetry. Many well-loved poems, from Arthur Yap’s “2 mothers in a hdb playground” (1980) to Alfian Sa’at’s ‘Missing’ (2001) to Joshua Ip’s “conversaytion” (2012), have given voice and soul to the local speech, vocabulary, and syntax. Although one would be mistaken to assume that Singlish is the de facto register of all Singapore poets—far from it—the use of Singlish in poetry today is ubiquitous enough to go unremarked. If Engmalchin’s dream was to cultivate in poetry a national consciousness, to hold disparate languages together, and to reflect a local reality, then many will consider Singlish as its worthy and undisputed successor.

Then arrives a book like parsetreeforestfire (Ethos Books, 2019) that engages with this language politics so intensely that it agitates for commentary—even disputing if a certain iteration of Singlish can qualify as Engmalchin’s only rightful successor. Shortlisted for this year’s Singapore Literature Prize, Hamid Roslan’s collection is divided into four sections: “parse,” “tree,” “forest,” and “fire.” While marketed on the front flap by its publisher as “a bilingual book of poetry” that translates between Singlish and English, the term is at once a misnomer and a sly declaration of the work’s self-consciously modernist poetics—involving what is more accurately transcreation, or even mistranslation and anti-translation. The result is what I would term a Singlish Modernism—the unanticipated sequel to Engmalchin Modernism—one that rebels and breaks free from a tacit tradition of using Singlish in a sincere, realist, and most authentic fashion. In a time when Singlish has become Uniquely Singapore (to borrow a tourism slogan), and even marketable to other Anglophone markets (Cheryl Lu-Lien Tan’s Sarong Party Girls is one example), this anti-orthodoxy can reinvigorate the debate on the status of Singlish in literary writing. Or, to quote the book’s virtuosic speaker: “You all always want to Singlish is our core our core, identity identity. Go fly kite. Go fly kite go Kalimantan. I want body, not propaganda.”

This thrilling voice accompanies us through the book’s four-act libretto. The reader who treats this book as a musical score (reading it “out loud with one ear covered with a finger” as Hamid’s mentor, Lawrence Lacambra Ypil cheekily puts it), pausing only to breathe in between the acts—be warned: the notes here are so far from speech, so hard to hit, that your entire musical range will be stretched and challenged. Sonic leaps and dips aside, as I’ve revisited this collection over the past year, it is instead the book’s borrowing of visual forms that have moved me to see its poems anew, to read in a different order. Already, the book cover renders the title vertically—a towering image of this nineteen-alphabet-long, one-word title—teaching the beholder to tilt their head, or rotate the book, to read the text. It is this visual play, displayed with similar verve throughout the volume, that allows it to consider Singlish with modernist eyes: as video, cinema, or art object.

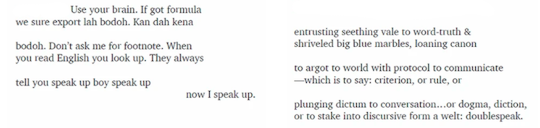

The first two sections draw most conspicuously on the visual layout of the bilingual book, rendering Singlish and English in parallel text. Traditionally, this layout functions like a gentle hand that points the aspiring reader to draw a word-to-word correspondence across the channel, and swim to their own tongue. Bypassing the need for a dictionary by giving you the life-jacket of a synonym, the bilingual book encourages you to head out to uncharted seas without the risk of drowning; in short, it instructs and secures. Hamid’s iteration of this format, however, refuses to hand-hold, and one suspects that his speaker is instead watching with a gleeful schadenfreude as the reader chokes for air. Witness the last lines of his opening pair of poems, an ars poetica that defends the book’s obscurity or esotericism (accusations possibly applicable here to the poeticisms of either language, depending on who the reader is):

Alternatively, the poem emphasises the specificity of its speaker as well as its reader—after all, much of the Malay is pure sound to me, made meaningful by snatches of partial understanding and gestured at via other contexts. And while the speaker on the left uses a variety of Singlish that borrows more extensively from the Malay (rather than the Chinese, the mother tongue of the dominant ethnic group in the country); the speaker on the right demonstrates he can walk a poem-length sentence in English and dilate it with polysyllabic, highly technical words. And while I glide from “dictum to conversation” to “discursive form,” I let “Kan dah kena // bodoh” chastise me—before confirming with Google Translate to make sure it is chastising me. “Don’t ask me for footnote,” the poem bluntly states, anticipating our clamouring (like A+ students asking for the model answer) before immediately shutting it down. In all its Singlish and jargon-filled glory, it refuses even the glossary (the choice of collections like Heng Siok Tian’s Crossing the Chopsticks (1993) or Joshua Ip’s Sonnets from the Singlish (2012)) as a way to preserve the aporia of a poem while providing a learning opportunity for the studious reader who consults the endnotes. After all, the glossary has always been contested in Anglophone publishing; where its strategic use can simultaneously access a wider readership, it also concedes that the monolingual reader should be prioritised. What remains to do then—and this is the book’s pedagogical style—is to reside in the confusion, to relish in the pairing of two stubborn texts at a time. Like an austere and ardent educator instructing their students to “look up”—the curt imperative which demands the student in me to memorise or master the text (look up!), or else to trust that the teacher knows best (look up!)—the text speaks up.

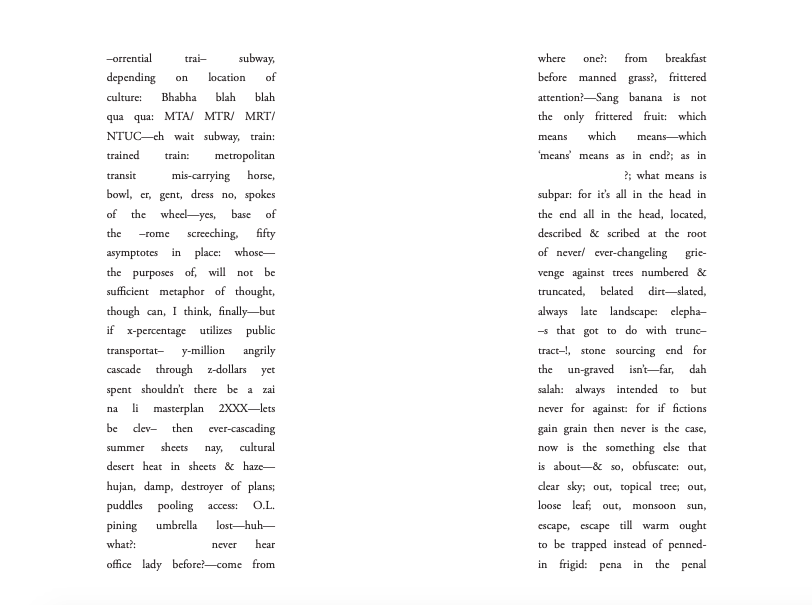

Rather than correspondence, the visual layout invites dissonance and juxtaposition. Hamid’s visual choice has more affinity with two-channel video art or the twin cinema poetic form than the bilingual primer. Anyone who has sat in a gallery, confronted with multiple screens, gradually understands that the point is not to follow disparate trajectories faithfully, but to spot the allusive connections between the screens; the point is to be washed over by stimuli and pick out whatever signal sparks your synapses, connecting a loose phrase on the left with a lone word on the right. This exercise can be frustrating for the reader who wants to “get it” the first time, but entirely rewarding for the repeat offender like myself who stares the poem down, reading and re-reading in different orders, to find new meaning. This way, you arrive at a different “translation” upon each return. After all, how does a standardised, word-for-word translation work if the status of Singlish has not even accrued to a standardised text—and should it? In another poem, the contestations over the standardisation of written Singlish are investigated, in which accepted forms of the creole tend to favour (and celebrate) misspelled Malay words mangled by Chinese phonology:

Due to unforeseen circumstances, the boy who

anyhow humtum got kidnapped by kumkum

because hantu see eye-rhyme not happy.Due to unforeseen circumstances, the boy who

jelat nasee lomak now his tongue always pull him

go & lick the dish. Now his family bankrupt.Due to unforeseen circumstances, the boy who

ask people to tiam-tiam his heart arrhythmia

because God keep go & spell check him.

Beyond staging the critique that “standardised” is another word for “sinicised” in the context of Chinese speakers bastardising Malay loanwords in Singlish—that is, the creole as a form of cultural hegemony rather than hybridity—the poem also renders linguistic error a matter of fatality and tragedy for the speaker who so chooses to misspell. As the poem on the adjacent page tersely translates: “Wherever possible, genocide occurred.” Take the first stanza, for instance, where the boy’s misspelling of hentam (meaning “to hit,” and in certain contexts, “to make a wild guess”) as “humtum” has unintentionally formed an eye-rhyme with “kumkum” and offended the hantu kumkum (an old woman ghost), who in turn kidnaps him. Typically a blood-sucking ghost who preys on young girls to restore her lost beauty, here the ghost preys on the errant speller—not intending to rectify, but to register her protest (“not happy”) at the visual ugliness of misspelling. The rest of the poem is replete with cases of misspelling and an imagined poetic justice—using “tiam-tiam” (from diam) forces a similarity with the condition of “heart arrhythmia”; “kachiau” (kacau) metamorphoses one into a cockroach; “scully” (sekali) causes scurvy; etc.—and the poem’s celebration of cross-linguistic sonic misfortunes ends with an ironic injunction for us to “spik proply.” On the adjacent page, parts of English speech lose their raison d’etre, “Tenses hushed in a corner // not knowing when was now.” Now the whole of the two pages becomes a crime scene, and I its detective.

After zooming in to parse each tree, the third section makes sure that we do not miss the forest for the tree, the render for the parse. Here is a long, narrative poem written in a set of parallel axioms—divided vertically this time, a more hierarchical division of the voices into main body (English) and subsidiary footnote (Singlish). But if footnotes have typically functioned as explanatory tools or a mark of scholarly meticulousness, here the speaker in the footnote talks back to the main text, referring to the speaker of the main text as an “ang moh lang” and makes clear his visually subordinate position within the text:

13. Before this present speaker & other present speakers

can speak, this faulty language must be confronted.——————

13 But nevermind, he very yaya say he want to fight

himself talking. Let him do lor. I sit down here see how

he sotong.

The visual field changes. Previously, we were taught to read for counterpoints, but here it would be wise to follow the cinematic workings of “forest.” The main text is rendered in a parody of plain writing, with the “clarity” of analytical philosophy, stripped of all the poeticism and linguistic dexterity found in previous sections. Ironically enough, the “clarity” renders the text turgid and somewhat meaningless (at least in the poetic context). Thus I look down to the footnotes not as an explanatory tool, but as a kind of subtitle so that I may follow the main plot and decode its poetry. For example, while “Axiom 54” quotes verbatim the British historian O.W. Wolters’s words on how cultures are localised, the footnote offers a much more emotional and lucid gloss:

54 This one also must learn from ang moh? Just take

one ang moh put another ang moh inside? Of course

must adapt to local context lah—if not how to use? Is

like you bring ice-cream go Pulau Ubin. Cannot right?

Can Singlish be made to speak axiomatically and philosophically? Here, folded into a footnote is a critique of worshipping Western scholarship and a resistance to using the obvious assertions of one’s lived experience to account for cultural phenomenon. This section bends Singlish to work as a cerebral and argumentative material able to participate in the commentary tradition of philosophy, on its own terms. One only wishes that philosophers would visit this section and read it with utter seriousness the way they treat Wittgenstein’s Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus.

After three sections that draw on the visual vocabulary of bifurcation, the final “fire” draws on synthesis (the very dream of Engmalchin). Formatted as a block text that runs across six wide-margined pages, the poem visually resembles the alphabet “I” on each page. Rather than make Singlish a means to access the lyric “I,” or render it as a form of consciousness to apprehend a social reality, it becomes a wall of words. This section looks almost like it should be sputtered forth from the mouth of the other self-translator Samuel Beckett and his one-mouth play, Not I—albeit a mouth which is obsessed with abbreviations, eats soon kueh at a kopitiam, and mentions Freud in the same line as Tiger Balm. The result is a text impenetrable when read, but rapturous when performed.

The great achievement of this book is in how disinterested it is in employing Singlish as a mode of capturing local speech patterns in writing, or as a way of inserting local flavour into the book’s mental landscape. It retains its singularity by refusing to be easily transformed into either a commodity object or a representative object; its goal is to become a subject. Thus, while Hamid states in an interview with the Quarterly Literary Review Singapore that what he deplores in most writers is the quality of “[being] precious or sentimental about one’s lived experience,” I am suspicious of placing him in an easy alliance with the post-identity impulses of the Language school poets. Rather, insofar as his linguistic experiments are built to ask formal questions of racial and postcolonial subjectivity, his affinities lie closer to Asian- and African-American avant-garde poets like Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Cathy Park Hong, or Harryette Mullen; the creole and code-switching poetics should also draw comparison to the Caribbean modernism of Kamau Brathwaite or Derek Walcott.

Here is Singlish atomised to a state of extreme diglossia, writ large as philosophical treatise, and impenetrable as a word vomit visual object. If its portmanteau-predecessor Engmalchin has come to signify the possibility of synthesising a national consciousness in the grips of British imperialism, I wonder what the neologism-successor “parsetreeforestfire” can go on to signify. A synthesis of the microscopic (“parse”; “tree”) and the macroscopic (“forest”) views aiming to defamiliarise our relationship to language? Or perhaps an attempt to set fire not just to language but the cauldron itself? And if Singapore poetry now wants to speak in entirely new ways, the book’s advice is simple: “THEN OPEN YOUR MOUTH.”

Shawn Hoo writes poetry and non-fiction. His poems have appeared in or are forthcoming in journals such as Voice & Verse Poetry Magazine and OF ZOOS, and anthologies such as A Luxury We Cannot Afford and EXHALE: An Anthology of Queer Singapore Voices. He graduated from Yale-NUS College with a BA(Hons) in literature, and is currently a teaching assistant trainee at the National University of Singapore (English Language and Literature Department). He is the editor-at-large for Singapore at Asymptote, and can be contacted via his email here.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: