Last month, Chilean poet Raúl Zurita won the prestigious Reina Sofia Prize for Ibero-American Poetry. He is esteemed as one of the most talented Chilean poets of the twentieth century, alongside Pablo Neruda and Vicente Huidobro. María de los Llanos Castellanos, the President of National Heritage, said that Zurita had been awarded the prize in recognition of “his work, his poetic example of overcoming pain, with verses, with words committed to life, freedom, and nature.” Having lived through Augusto Pinochet’s dictatorship (1973–1990) and, like many other Chileans, having been arrested and tortured under Pinochet’s regime, Zurita’s work addresses the violence committed against the Chilean people. His books in English translation include Anteparadise (translated by Jack Schmitt), Purgatory (translated by Anna Deeny), INRI (translated by William Rowe), and Song for His Disappeared Love (translated by Daniel Borzutsky).

For a year now, since October 2019, Chile has been gripped in fresh political protests, sparked by a rise in subway fares. These have been the biggest protests in Chile since the end of the dictatorship and violent clashes between protestors and police have resulted in deaths, injuries, and arrests. In this essay, Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Iran, Poupeh Missaghi, reflects upon Zurita’s response to state violence in his work. She draws a comparison with her native Iran, which similarly faced a US-backed coup (1953) and has recently experienced mass protests in response to economic injustice. By exploring Zurita’s ability to express the history and suffering of his country, as well as her own relationship to his body of work, Missaghi considers the importance of finding one’s literary heritage.

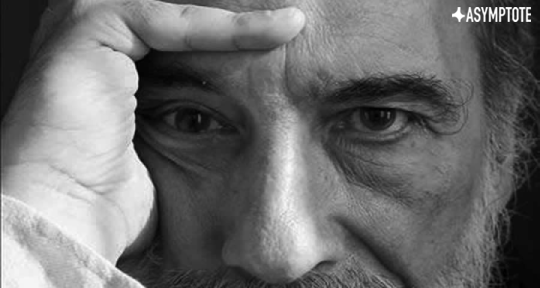

The first time I saw Raúl Zurita read was in 2016 at the University of Denver. My skin felt raw, not just in the presence of his words (some of which I had read before), but also in proximity to his voice—deep and powerful yet carrying its fragility on its every note, accompanied by the trembling in his hands and torso. Trembling that wasn’t hidden or performed, but simply part of the way he carried, had to carry, his body and his voice as they carried with and in them the bodies, voices, and memories of others.

In a foreword to Purgatory, C. D. Wright says, “Instead of speaking for others, Zurita channels their voices.” There is an important difference here: the poet is not sitting on the sidelines and observing, but rather entering the purgatory himself. Whether through the intentional acts of hurting himself in his younger days (“branding his face and burning his eyes with ammonia”) or through the unasked-for Parkinson’s disease in his later years, Zurita literally embraces the pains he and his people have lived through. About his disease, Zurita notes,

I feel potent in my pains, in my curved spine, in the increasing difficulty of holding the pages when I read in public . . . I might have a bizarre sense of beauty, but my disease feels beautiful to me. It feels powerful.

Being in his presence over the years, I cannot help reading his Parkinson’s as another layer of his life-long labor of memory—his nerves being affected, being burdened, and his whole body becoming a witness who speaks even when he is not using verbal language.

***

The first work of Zurita I read was Song for His Disappeared Love, which for some reason I always remember as Song for His Disappeared Self, which is perhaps just a ghost of the same title. I read the book in a documentary poetics class taught by Eleni Sikelianos, and that was the beginning of my fascination with Zurita’s work, as well as with that of the translator Daniel Borzutzky. In Song for His Disappeared Love, Zurita narrates the pains of different countries of the Americas. Toward the end of the poem there are two drawings that resemble maps of some imaginary terrain. The niches in the first map are empty, filled with a void. The ones in the second include names of countries. Looking at them, the preceding pages of text begin to seem like another map, of partitioned city blocks or a cemetery with tombstones made of words. The last stanza of the poem before the drawings reads,

30. Is the tomb of the country’s love calling? Did you call out of pain? Out of pure pain? Was it out of pain that your love cried so hard? . . . are they calling me? Are you calling me?

This is one of the recurring themes in Zurita’s work: the psychological traces of political history on both the people and the landscape, and how one responds to being called by the voice of one’s pained country coming from the depths of darkness, long after the sources of that pain and the bodies emitting that voice are gone. This voice carried through in Zurita’s poems and the embodied, circular manner with which he approaches the topic have become, since those first encounters, a signpost on my path to addressing the pains of my own country, Iran, miles away from his. Because, of course, history repeats itself; even if this repetition is not in the details—though it can be—but more so in the psychological effects and fissures it leaves in our souls.

Both Chile and Iran have faced US-backed coups that disrupted the movements of their people toward building civil societies—Iran in 1953 and Chile in 1973. Both people have lived under dictatorships, state violence, imprisonment, torture, and under the shadows of the ghosts of history, the dead, and the disappeared. Both people have protested and fought back, paying a high price—physically, emotionally, and mentally. In 2009, Iranians faced a severe crackdown with the use of batons and bullets when they protested the disputed presidential election. Since then, many smaller protests have been held by laborers, teachers, feminist activists, and others, all reacted to unfavorably, if not violently. The recent protests in both Iran and Chile in 2019 happened in response to, among other issues, economic injustice: in Iran, they followed the overnight 300% increase in the price of gas; in Chile, the raise of the subway fare. Both protests were met with police brutality. In a video from the streets of Chile, which Daniel Borzutzky links to in his Op-Ed piece for the New York Times, people walk in a line on the sidewalk before security forces begin attacking them with batons. The similarity of that video with videos and pictures from Tehran in 2009, especially one in which security forces, in similar gear, attack unarmed people on a sidewalk, is devastating to me.

And this is not just happening in Iran and Chile. These are just two places among an increasingly long list of countries, including the US, whose people, fed up with corrupt governments, have come to the streets, considering public protest and presence with their bodies as one of the few means that remain to have their voices heard. Everywhere it is us, the people, against the same global, avaricious system that simply lives in different incarnations in different corners of the world, wearing different hats, and calling itself different names.

Attending to this struggle and the violence in response to it, Zurita’s Song for His Disappeared Love does not isolate the destiny of one self from the other, one country from another, the natural from the unnatural. “What is then mapped is not only a particular personal and collective experience in Chile but the countries of America as having arrived at their shape through similar experiences,” states William Rowe, another of Zurita’s translators. One can easily expand this definition to include countries all around the world.

Zurita’s images of the tombs of countries in Song for His Disappeared Love, drawn out as if by hand, feel even more harrowing because they are preceded by the voices of those who are alive—alive and searching for the dead, including Zurita himself: “Now Zurita—he said—now that you got into our nightmares, through pure verse and guts: can you tell me where my son is?”. His images and his text offer different possibilities of writerly and readerly interaction. The juxtaposition reveals that one’s relationship with one’s country and its (hi)stories is a labyrinth; navigating through it to find a way out—or rather in, as deep as possible—demands different forms of breathing at different spatiotemporal stages, while being courageous enough to face the gaps.

Daniel Borzutzky, in his introduction to The Country of Planks, notes, “Zurita’s writing can perhaps be seen as an attempt, as he has said in conversation, to prevent the disappeared from disappearing again.” This has also been my hope and intention in my work, especially in trans(re)lating house one.

Inspired by Zurita’s sensibilities, I created a multi-genre map that takes us in one part to tombstones made of documentary encyclopaedic details about some of those who have lost their lives to various manifestations of state violence in Iran. His experimentation with form in Song for His Disappeared Love and in his other books, for example in Purgatory where he includes his echocardiography in “The New Life,” opened the door for me to explore the impact of visual forms of expression in my work, for example by including word drawings to represent the world of dreams, an important layer of not only personal but also our collective psyche and (hi)stories.

***

Wright ends the foreword to Purgatory by saying, “Raúl Zurita has remained mindfully undistracted from his original task of transcending the unbearable through art and of proposing the possibility of Paradise even in the face of unimaginable suffering.” But I wonder if he has transcended, or ever intended to transcend, the unbearable. It seems to me that he has rather gone to the depth, settling in the eye of the storm, inhabiting the unbearable, the unimaginable. It is only from right there, and not from beyond purgatory, that he has been able to channel the emotional burdens of a place and time, and to envision the possibility of Paradise.

I do not read his Paradise as a pure, unearthly, spiritual or religious domain. For me it is a flawed, humanly one, right here, right now, sharing porous borders with the purgatory that keeps reviving itself every day as a result of new atrocities committed all around the world, a purgatory constantly on the verge of metamorphosing into hell. This Paradise is a space that comes to life in Zurita’s gestures of empathy, in his attempts to see and hear, and acknowledge the human and nonhuman that has been wronged by the human, in his offering of a kind, attentive presence tending to the self and the other, aiming for love, while we are in a state of mourning, surrounded by ongoing suffering. Forrest Gander notes, “Zurita gazes at the strafed wreckage of self and country with the hope that he might yet find some durable faith to bind himself, and all of us, to the world.” It is this very hope to find this very faith to “bind” us to each other and to the world that can make Paradise possible, even though it is never truly realized. We never arrive at it; we are always only striving for it.

In his lifelong endeavor to document, love plays an important role for Zurita: “I touch your flesh, your skin, and the tips of my fingers search for yours because if I love you and you love me perhaps not everything is lost.” Later on that same page, he writes, “. . . because if I touch you and you touch me perhaps not everything is lost and we can still know something of love.” The repetition is key here. We need to be reminded. Of our need for love and for touch. Of their power over our lives, of their being our only saviors.

During that same trip Zurita took to Denver in 2016, our class met with him once more at a gathering at Selah Saterstrom’s house. I sat down on the floor close to him and, with the residues of my once-upon-a-time Spanish, tried to absorb his responses to our questions in my body, while listening to and analyzing with my mind the English words of the interpreter. I recently found, by accident, a recording of that gathering on my old phone. Zurita’s voice is distant, his interpreter’s closer; a reminder that what I read of his words—so powerful, so haunting—is still not his, but his words mediated through his translators’. In a section of the recording, the interpreter is joined by the people in the audience, everyone trying to transfer the complexity of Zurita’s comments, creating a multivocal tracing and retracing of words to find the best equivalents. The gist of that collaborative expression comes to,

Poetry is the hope of that that has no hope. It is the possibility of something that has no possibility, the love of that that has no love. We are condemned only to persistence, knowing that there is a lot of failure waiting for us, but we have to persist and persist in the construction of a Paradise, although all evidence at hand is telling us that it is just all craziness.

It is craziness, indeed. But what choice do we have other than to persist?

***

Over the years, I have devoured more and more of Zurita’s writing. His incantations aiming to resurrect the dead, or rather to remind us that the history’s dead are never really dead, even if they remain dead forever. I’ve watched online videos of him reading along with several translators/interpreters. After listening to so many, I still consider the recording of his reading alongside Laura Hope-Gill my favorite.

In that video, for some reason, I feel his original language most vividly and most intensely as an embodied voicing of history that doesn’t really recede into the past. In the imagery, the pauses, the rhythms, the repetitions, the investment in love, the coming together of the “I” and the “you,” surrounded by and being and becoming one and the same with death and the haunted landscape that is so beautiful it aches me to look at. There is something special in the way he and Hope-Gill take turns to read together that I have not found in the other readings. Maybe it is the force of Zurita’s words and voice followed by the solemn calm of Hope-Gill lingering on the poetics of each and every line. Maybe it is the breathing of the two that can be heard throughout the recording. Maybe it is Zurita’s eyes as he listens deeply and intently to the voice of the woman voicing him voicing the absent others. Maybe it is the silence all around. Maybe it is the sign language interpreter whose voice we hear by watching her movements as she too translates. I keep returning to that video and every time I pause and rewind to listen to their reading of “Flores” (“Flowers”) over and over again:

A face is a face in a desert in flower / I hear white plains flower / I heard whole deserts cover themselves with flowers / A flower is a face in the solitude of the desert as a face is a flower in the solitude of things / A face hears years, seasons, endless lives that finish / A flower just a few days, a few twilights, a few endless nights that finish / A face is another flower that finishes / I heard infinite deserts that had come into flower destroyed / I’m called Zurita and I tell you these things just like I could tell you others / Maybe the demented flowers love one another.

Whenever I write or read these words on the page, I can only hear them in Hope-Gill’s voice, accompanied by an image of Zurita standing there and looking, his eyes so burdened and yet so alive. The circularity in these lines feels in my body like being taken in the middle of a gentle sandstorm. Gentle but a storm nonetheless, it is running through the desert, exposing life underneath the dunes—the the flowers, the faces—only to hide them again a moment later with a new formation of sand, to once again expose them, making any mapping of the flowers or the faces or the desert impossible. I hear that line in the end where he introduces himself as a gesture to make these words formal, official, as if in a court of justice, reminding us of the choices not just he, but we too make as writers, poets, artists, to tell these things or other things. What if we said these instead of those, those instead of these?

***

Years later after those first encounters in Denver, I saw Raúl Zurita once again, reading alongside his translator William Rowe at The Poetry Project, as part of the PEN World Voices Festival in New York, in May 2019. I arrived early at St. Mark’s Church. There were two large branches of small pink flowers on the two sides of where he was to sit. The late-spring evening light was coming through the color-glasses of the church windows, spreading over the still-empty audience chairs forming a semi-circle in the middle of the large space. He walked in with a few companions and after a while sat there on his own. I walked to him to say hi and introduce myself. To my surprise, he remembered me.

In Denver, we had talked about the possibility of an interview for a Persian-language literary journal. I had just published a translation of an excerpt of one of his poems and written a piece to introduce him and his work to an Iranian audience. After our conversation, I had emailed him and thought he didn’t write back, only to find his response a while later in my Junk folder. I emailed back; he was traveling. We decided to do the interview later. We never did. The journal closed down, and I got lost working on my own manuscript. Recently I went back to those few emails. I had written in English. He had responded in Spanish. Reading through our communication, I was once again delighted by his generosity and kindness, by his ability to see through, by this connection that happened via the extensive language on his pages and then through the few words we exchanged in person.

He remembered the details of our meeting and my manuscript and the fact that I was working with Laird Hunt. I told him about my manuscript becoming my then-forthcoming book trans(re)lating house one and about how his voice had been such an influence, accompanying me all throughout the process. Once again he spoke in Spanish, I spoke in English, but we managed to get through to one another. I told him about the book I was reading then, The Remainder by Chilean author Alia Trabucco Zerán (translated by Sophie Hughes, Coffee House Press, 2019). He talked a bit about the book, said something about knowing Zerán’s parents.

At the reading at Denver, I had Zurita sign my copy of INRI (translated by William Rowe, Marick Press, 2009), not on the first page as is usually done, but on the title page of the section for “Flowers,” which to this day remains maybe my favorite poem of his. In the event at The Poetry Project, I once again stood in line to have him autograph yet another copy of INRI (translated by William Rowe, NYRB, 2018). Yes, literary fandom, I know. But perhaps I also wanted a memento that would mark this new in-person encounter to remind me of all the ways he—his person and his works—and I have encountered since that first meeting in 2016. It was as if I wanted his handwriting, still the same but giving life to different words, on two different dates and cities, to mark the passage of time.

The very next day, Zurita read—along with Christos Ikonomou, Ahmed Naji, Ma Jian, Marianna Kiyanovska, Kirill Medvedev, and Jennifer Clement—at another PEN event called “Cry, the Beloved Country.” He looked tired sitting there listening to others and looked even more vulnerable and burdened standing up to read, while translations of his words, by various of his translators, were projected on the screen behind him, becoming visual bodies of language behind his body. After the reading, I went to say goodbye and wish him safe travels back home. He seemed to not remember me and asked for William Rowe’s help to translate what I was saying.

***

Finding one’s literary lineage is a strange thing. Perhaps like love. You don’t necessarily find the voices that speak to you among your own people or in your own language. To tell the (hi)stories of your place and time, you might need the presence of bodies and souls from all the way on the other side of the world, from other times, to take your hand and guide you back into what is close to you, intimate and for that reason hard to access and express. And it is not just their writings that inspire us, but also their very personhood, how they carry themselves in the world that they write about.

Speaking about the need to look deep into traumatic events of the past and present in an interview by Borzutzky in 2015, Zurita says,

These are situations without hope. [The Country of Planks] is an attempt to arrive at, to touch the darkest zones, the most wounded zones of our experience and our history. Because only by arriving at these points is it possible to reimagine the ability to hope, and to reimagine the possibility of a new life because if you don’t look at those darknesses, at this capacity for evil, then you can’t ever imagine something that has a bit of light.

As writers and artists, we cannot really walk into the darkness and wade into “the most wounded zones” all by ourselves. We need others we can trust to accompany us there. Raúl Zurita, with his perseverance in being a witness to the atrocities affecting his people throughout all these years, allowed me to attempt to become one for my own (hi)stories and people. I’m thankful for arriving at his work and meeting him in person, for being able to have his vision and voice accompany me while I was trying to find the voices and forms that would allow me to bring to the page the complex being of my Iran that is different and yet similar to his Chile.

Poupeh Missaghi is a writer, a translator both into and out of Persian, Asymptote‘s Iran editor-at-large, and an educator. Her debut novel trans(re)lating house one was published by Coffee House Press in February 2020. She holds a PhD in English and creative writing from the University of Denver, an MA in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University, and an MA in translation studies. Her nonfiction, fiction, and translations have appeared in numerous journals, and she has several books of translation published in Iran. She is currently a visiting assistant professor at the Department of Writing at the Pratt Institute, Brooklyn.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: