The role that fiction plays in both relating and shaping our reality is pivotal, and this power that lies in representation is oftentimes an essential source of strength for individuals who persist under oppression and negation. For writers of queer texts in the contemporary Arab world, the complex paradigm of politics, history, storytelling, and interiority has culminated in an explosive multiplicity of voices and experiences, coming together in revolutionary expression. In this essay, MK Harb, Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Lebanon, focuses in on three novels which engage their queer characters and environments in surprising and enlightening narratives, denying easy categorization to tell the poetry of the personal.

Oftentimes, when discussing the subject of queerness in contemporary Arabic literature, the idea of time travel arises in tandem. I say this only half sarcastically: it is not strange for a piece of criticism on a twenty-first-century Arabic novel to have an introduction valorizing the homoerotic poetry of Abu Nuwas, an Arabo-Persian poet from the ninth century. To put this in literary perspective, imagine an article on Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous beginning with an introduction discussing a queer text from the European Middle Ages. This bemusing conundrum is a product of orientalist academic training, often popularized by the faculties of Middle Eastern Studies departments across Western universities: a standard that singles out race in using the past to justify the present, imagining an uninterrupted continuum of the “Arab” experience irrelevant of space and time.

This obsession with the queer past of the Middle Eastern archive rarely comes from an investigation into the transgressive capabilities of past writings; rather, a strong exoticism governs this curiosity, and it often falls into the trappings of fetishizing the body and the experience of male love. Now, the subject of queerness in contemporary Arabic literature is itself fraught; many countries across the Middle East and North Africa engage in heavy censorship of books, particularly ones with characters that defy the hegemony of national and patriarchal orders. The other dilemma is that of language—in the past years, many queer Arabic characters came to us through writings in English or French. Whether it is Saleem Haddad’s Guapa or Abdellah Taïa’s An Arab Melancholia, the question of translating the “Arabic queer” and its various experiences looms large. Regardless of such constraints, however, the canon does not lack for contemporary contenders, which shed some much-needed light on the developments in queer livelihoods and philosophies. In this article, we will go on an elaborately queer journey through the works of Samar Yazbek in Cinnamon, Hoda Barakat in The Stone of Laughter, and Muhammad Abdel Nabi in In the Spider’s Room. What binds the protagonists of these novels together is not simply their queerness, but also their strong interiority and internal monologues, through which they shatter and construct social orders.

Cinnamon, written by Syrian author and journalist Samar Yazbek, is the story of a lesbian affair and underage sex in which social order and class anxiety collide. The novel, heavy on symbolism, often uses signifiers to indicate the progression of tumultuous events. It begins with the protagonist Hanan noticing “a streak of light” from a door that was left ajar, which leads her to discover that her servant, Aliyah, is in bed with her husband. The shock and dismay of Hanan at that moment, however, is not that of a heterosexual homemaker who becomes aware of an affair; rather, it is the distress of a woman finding her lover in bed with her petulant husband. From there, the audience enters a psychosexual saga in which Hanan evicts Aliyah from her house, and the audience learns about their romance through a series of flashbacks and recollections.

Hanan belongs to the “unbearably regimented” and bourgeois world of pale Damascene women who were destined to marry in the interest of maintaining family honor and business networks—exemplifying the coupling of capitalism and Islamic patriarchy in pre-war Syrian society. Aliyah, on the other hand, comes from the Al-Ramel district, described as an area where “impoverished Palestinians and dark-skinned Ghouranis . . . lived alongside the destitute people who had arrived from the coastal mountains.” The expert craft of Yazbek is evident in her construction of two strikingly different spatialities; she hones in on the class discrepancy between Hanan and Aliya so astutely that one often questions whether it is a story of love between two women, or that of sexual abuse by an employer. In between Hanan’s bouts of ennui and dissatisfaction with her life, she begins to crave her “darker-skinned” servant, Aliyah, lusting after her like a predator. This pedophilic chase then turns to an obsessive love on the part of Hanan, even as the class hierarchy between them remains. This manifests most strongly and most absurdly in a poignant scene in which Aliyah falls asleep with Hanan in bed after intercourse, and wakes up to Hanan admonishing her for staying in her chambers the next morning.

Throughout this tumultuous chase, Aliyah is not solely a naive victim with “supple fingers,” though the question of molestation and underage sex constantly looms large. She realizes the extent of her power as her mistress surrenders to infatuation, and this leads her to a bifurcating manipulation to circumscribe her control of the house. We come to understand that their relationship is not simply about lust and desire; it inexplicitly extends into trauma, power, upward mobility, and control. Scholar Jolanda Guardi, in her analysis of the text, explains that their affair “is experienced as a shelter, as an alternative, on the one hand to an unsatisfactory marriage, and on the other hand to the class subaltern condition.”

Guardi’s point can also extend to the other women who appear in the novel. Often, when Hanan smells the scent of cinnamon, she is reminded of her other sexual experiences with Syrian women—Nazek, the older predatory woman, who lusted over her and introduced her to the secretive and palatial lesbian saloons; her cousin who sexually assaulted her during a ritualistic Hamam session before her wedding night. Cinnamon tea, we come to learn, was an elixir that Syrian women drank to ease their first night of intercourse with their husband; yet, in Yazbek’s novel, it stands for a tantalizing male erasure, rendering them as hapless and helpless subordinate individuals. Cinnamon also represents the extent of women’s agency and the power of same-sex desire in a novel where the discourse takes on an unabashedly feminist undertone. Yazbek’s prowess is her ability to demonstrate the freeing qualities of love between two women, but also her strong and realistic grasp of Syrian society. She positions these relations in a complex web of constellations built on discretion, racial hierarchies, financial interests, and abuse.

In The Stone of Laughter, Hoda Barakat explores similarly the aforementioned possibilities of liberation and change. The novel, which received the prestigious Al-Naqid Prize, unfolds amidst Civil War Beirut (1975–1990) and documents the trials and trepidations of the protagonist Khalil. While possessing a traditionally male name, one comes to realize that Khalil embodies both masculine and feminine qualities, and is a potentially genderqueer character. Published in 1990, the novel was radical in its time for shattering the rigid definition of the literary protagonist in Arabic literature. Analyzing the politics of Barakat’s writing, scholar Kifah Hanna highlights that “Barakat’s choice to write exclusively in Arabic about homoeroticism and queerness in spite of her being fluent in French is of particular significance.” This recalls the earlier point about queer Arabic characters coming to us from translated English and French writing. Barakat’s choice to write in Arabic is inherently political for two reasons: first, it defied a normative tradition of Arabic literature to discuss “taboo” topics in English or French, towards an elite and diasporic audience; second, it aimed to impact a vernacular audience that mainly spoke and read in Arabic, and in literary and publishing circles highly dominated by heterosexual men.

The story of Khalil itself is a sardonic and surrealist one; the anteriority of his character is so wickedly strong that the reader often forgets about the war raging in the background. In the course of the novel, we encounter his situations with hilarity and heartbreak. Barakat writes with scathing honesty and an astute ethnographic lens. Her Beirut is textually real, from the power cuts to the squalor and the loneliness that haunts the apartment buildings, refusing to fall into the typical trappings of romanticizing a city during calamity. In addressing her character’s place within it, Barakat captures uncomfortable moments of bodily reckoning, such as Khalil’s feminine legs and the vitality of his masculine love interest, Naji. Through depictions of visceral experiences—such as one in which a man sitting comfortably in his underwear turns to both a homoerotic encounter and a reminder of bodily discomfort—Barakat captures the insidious discomfort that haunts a person at war with their own physicality.

Scholar Kiffah Hanna analyzes Barakat’s careful and intellectual treatment of desire as a “sensitive, sophisticated dialectic of homoerotic desire in confrontation with the strictures and inherited assumptions of a hostile culture.” The hostility of being “out of place” is important to reflect on in Barakat’s treatment of Khalil, for he encounters multiple displacements and alienations. The first is his alienation from the participatory violence surrounding Beirut, as he very rarely engages in identitarian or sectarian rhetoric like the men surrounding him; his concern about belonging does not unfold through performing masculinity in war, but through his inner thoughts and anxieties. This alienation often becomes a menacing psychological ordeal as Khalil grapples with emotions of shame and confusion while confronting his gendered difference and his love for men. Hence, the author’s use of gender to espouse the rhetoric of nonconformity is both liberating and taxing; Khalil is able to transcend normative experiences of violence in his city of Beirut, yet is often fatigued and saddened by his own perceived difference. This unfolds in a brilliant and Freudian manner in Khalil’s dream encounters. In one dream, Khalil runs in the meadows, laughing like the Egyptian actress Mervat Amin, known for her sensuality and femininity. A man called Raafat runs after him and they reach a corner where he romances Khalil. At that pivotal moment, Khalil’s former lover Naji appears with bloodshot eyes, angry at the display of infidelity—he then takes hold of Khalil and caresses him. At that point, Khalil wakes up feeling distraught and alarmed. In this brief dream, Khalil projected the image of Mervat Amin to embody a desire for a different and more feminine bodily experience; yet at the same, his gnawing guilt manifests in a past lover surveilling and policing his romantic pursuits.

Barakat’s use of a genderqueer character is a way of introducing and debating the possibilities and complexities of change. Reading the text, one cannot help but think of Angela Davis’ recent remarks about the pathway for abolitionist feminism being paved by women, queer, and transgender communities. In her lecture, Davis argues that these groups and their life experiences chart the way for radical change, which would stem from abolishing the gender binary. Barakat builds on this concept by using the space and time of Khalil to cohere reflections on love, existence outside the gender binary, and the unmaking of society. However, Khalil is not simply a progressive emblem of change; like the complex characters in Samar Yazbek’s Cinnamon, he still deals with the grueling gaze of society and the ramifications of his difference. This manifests most strongly near the end of the novel, in which Khalil takes on a violent and heteronormative persona. Ending on a cynical note, we see that Beirut and its violence—even if for a brief moment—is able to take hold of Khalil and his body.

These ruminations on the self and the lonely encounters with past trauma are also a strong cornerstone of Egyptian author Mohammed Abdel Nabi’s In the Spider’s Room. Shortlisted for the 2017 International Prize for Arabic Fiction—an ironic honor after it was banned in the host country, the UAE—the novel follows a gay man, Hani Mahfouz, arrested during the infamous 2001 police raid on the Queen Boat in Cairo, Egypt. During the arrest, the Egyptian state subjected a number of gay men to humiliating trials and unjust prison sentences. Hence, in its treatment of the subject matter, the novel is one of few in the contemporary Arabic canon that deal with the carceral and gender-based violence that the state practices against queer people. However, one would be amiss to characterize the novel as a struggle for liberation or a Stonewall-esque narrative; the communal aspect of the story is fragmented, privileging the protagonist Hani and his present dilemmas.

The Queen Boat saga renders Hani speechless and his therapist recommends journaling and writing in order to release trauma and regain his ability to talk; the journaling then unreveals his past and the adventures of a gay coming of age in Cairo. Hani’s recollections are often blemished with the clichés of writing a gay character—an elite character, to be specific; this is most evident in the character’s frequent sexual adventures, undertaken to remedy the loss of his lover, Raafat, who married a woman in an attempt to remedy the shame of his sexual orientation. The predictability can be distasteful, and Hani’s inclination for ennui and self-lament are occasionally tedious. Nevertheless, in writing him, Abeld Nabi hones onto an important experience of discretion—a common association with certain Arab gay men in their region.

The need to be discreet is contributed to society, fear of the state, and financial interests—whether it is public tarnish, or in certain cases, the life-threatening risk of being outed to the family. The fear of being exposed to the security apparatus of the state with its draconian torture techniques—such as anal examinations that have occurred in countries like Egypt and Lebanon—also looms large in the imagination. Such oppression creates a culture of “discretion” that permeates into sexual affairs and relationships, which are in turn often unconsummated out of fear of moral injury or physical threat. Hani falls into the category of the gay male who is discreet, yet somewhat out; he did not marry a woman, and has resisted the need to start a family. Nevertheless, he is careful with his actions, though this does not mean he restrains his desires or lives in isolation; he regularly indulges in flings, and attends a number of lavish and enticing queer parties. Even within the surreptitiousness, there is a trusted and engineered network of navigating society.

This mode of life is, however, shattered at the moment of his arrest. Suddenly, the networked interests of discretion elapses, and the trauma and shame of being gay in his society rise to the fore. In the end, Hani is not forced to endure an uncertain destiny or a prolonged arrest due to his status in society, and was protected by a classist system that was able to secure his release. However, upon regaining his freedom, the city itself becomes a cage, and he enters a state of bodily and psychological isolation from his society. His inward inquisitions becomes prison-like, riddled with shame, and a punishing investigation into the self. Hani’s Cairo—similar to Khalil’s Beirut—is hostile, a city in which insidious patriarchy trumps whatever freedom urban life promises. As the Egyptian writer, Omar Robert Hamilton, once wrote: “The City Always Wins.”

From Beirut to Cairo to Damascus, these three texts draw upon the varied and society-specific experiences of the “Arab queer.” Whether it is Khalil’s gender nonconformity, Aliyah and Hanan’s embattled affair, or Hani’s traumatic experiences, it is impossible to narrow this vista into a monolithic or uniform category. The beauty of these novels, despite their often-tragic happenings, is their utilization of language to break down hegemony and to expand the scope of representing society, weaponizing the political agency of fiction in order to bring society’s uncomfortable conversations to the surface. They construct fully formed worlds while presenting us with engrossing and compelling experiences, stratified along class, cultural, and societal lines. Hence, their work is inherently radical; it combats the normative expectations laid down by the state, which trickle down to society and its many apparatuses, from the publishing press to the security agencies.

However, while writing this article, a certain disquiet haunts our outward look into the future. In the past years, there has been a state-sponsored increase in homophobia across the Arab region, from Lebanon to Egypt—the most recent manifestation being the manhunt of the Cairene LGBTQ after the controversial Mashrou’ Leila concert in Egypt, which most recently claimed the life of activist Sara Hegazi. This begs the uncomfortable question on whether or not literature in Arabic, dealing with queer topics, will find a place in the politically charged atmospheres of cities such as Beirut and Cairo—as Arundhati Roy once wrote, “Little events, ordinary things, smashed and reconstituted. Imbued with new meaning. Suddenly they become the bleached bones of a story.”

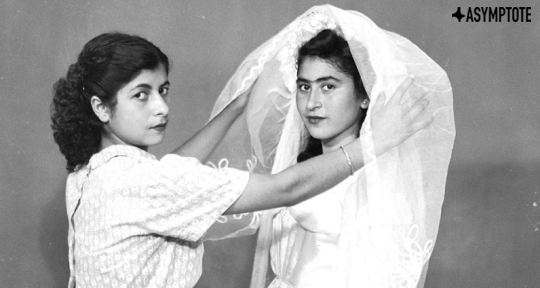

Image credit: Hashem El Madani

MK Harb is a writer from Beirut, currently serving as Editor-at-Large for Lebanon at Asymptote. He received his Master of Arts in Middle Eastern Studies from Harvard University in 2018. His work is published in BOMB Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, Hyperallergic, Art Review Asia, Asymptote, and Jadaliyya. He is currently working on a collection of short stories pertaining to the Arabian Peninsula.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: