Writer, translator, and scholar Agnieszka Taborska reflects upon the literary and historical precedents of the global lockdown in these excerpts from A Woman Awaiting (The pandemic from a garret), our selection for this week’s Translation Tuesday. In coping with the trauma and uncertainty of the current pandemic, Taborska offers a bookish yet personal perspective, one informed by an expansive breadth of literary knowledge as well as familial accounts of another historical tragedy: the Nazi occupation of Poland. Paradoxically, the speaker’s isolation takes us on a necessarily cosmopolitan journey through books, recontextualizing the pandemic through the lenses of Gabriel García Márquez, Joris-Karl Huysmans, Bram Stoker, and Spalding Gray, among others. With candid, irreverent wit, Taborska chronicles her daily thoughts about the absurdities, losses, and shared anxieties of our current global crisis.

What was a day, measured for instance from the moment you sat down to your midday meal to the return of that same moment twenty-four hours later?

Thomas Mann, The Magic Mountain [1]

Friday, April 3

With every passing day our activities take on more of the characteristics of ritual. In the morning we top up the humidifiers on our radiators, rolling up the blinds to let the plants soak up the sun from the first minute, and wiping down with a wet cloth the leaves that haven’t had time to gather dust since we last cleaned them. For the umpteenth time we move the flowerpots around to make their residents feel as comfortable as possible. The tiles, the bathroom, the bathtub, and sink have been scrubbed raw. We recall with relief that there are still windows to be cleaned. We have shifted the furniture around, surprising ourselves with the audacity of our experimental solutions. Our new routine makes us laugh at the previous one. We strive to create hothouse conditions in our limited space. When all this is over, will we deliberately let our flat go to seed? Will we stick to a daily agenda or—on the contrary—will we turn day into night, drop in on our friends unannounced, wake up our neighbours by playing loud music at dawn, will we ditch every schedule?

The habit of checking the weather forecast is now a thing of the past. The degree of air pollution has also become irrelevant. A million dollars to anyone who, asked out of the blue, can name today’s date and day of the week without having to stop and think. On the other hand, we are getting expert at telling the hour. We have our hand on the pulse. We are aware of the days getting longer. We are familiar with the path of the rays of the sun as they move across the floor. We could tell the shadows out in the street where and how far to fall.

Our window looks out onto a small grocery store. We have noticed a pattern: young people go in wearing gloves and face masks, the old behave as if nothing was happening. Our activist neighbour picks up litter from the pavement as usual. A sight that takes me back to the past.

The dogs waiting outside the shop are surprised that their two-legged friends have suddenly been spending so much time with them. Two Labradors who came with a gentleman on a bike kill time by simulating copulation, as always. They mount each other and make rubbing motions, too brief for ‘anything’ to really happen. The infection has not impaired their erotic fantasies.

Of course, conspiracy and pseudo-scientific theories are thriving. It’s all America’s fault. Or it’s Russia’s doing. It’s an international conspiracy. The virus was created in a lab in Wuhan from which it ‘escaped.’ It is a biological weapon (who is the intended target is anyone’s guess). The virus has been cultivated by ecologists in order to slow down and cleanse the world. There is no such thing as a pandemic, it’s just someone out to intimidate people. The virus, once exhaled by a sick person, sinks to the ground and stays there, trampled to death by heavy boots. Certain minds hang on to these theories for grim death. The number of such minds seems to be growing.

Tips on how to avoid getting infected proliferate. My inbox is full of emails guaranteeing that nothing beats the virus like Vitamin D. And offering discounts.

From the time the cholera proclamation was issued, the local garrison shot a cannon from the fortress every quarter hour, day and night, in accordance with the local superstition that gunpowder purified the atmosphere. (Gabriel García Márquez, Love in the Time of Cholera [2])

These are times for slowing down and creating lists. Among the most popular are lists of professions that have ‘temporarily’ lost their raison d’être. They remind me of Y., who for many years kept a notebook with names of friends who died. Once their number exceeded the number of friends still alive, Y. gave up. We’ll do the same, no doubt. Right now topping our list are jobs that have been hit most suddenly: taxi drivers, restaurateurs, waiters and waitresses, actors, dentists, freelancers, beauticians, pedicurists, make-up artists, hairdressers, therapists, masseurs, simultaneous translators, as well as owners and employees of shops that sell non-essential goods—florists, small publishers, furniture shops, and the like. Online fortune tellers, on the other hand, have no shortage of customers.

It’s because we are getting superstitious. Online book readings usually conclude: ‘See you tomorrow, if all goes well.’ People who keep diaries avoid using the next day’s date before midnight. Camus, too, noted among the population of Oran an interest in prophecies that grew with the spread of the plague.

Good Friday, April 10

A journalist throws up his hands and says there’s never been an Easter as tragic as this. He fails to mention that this only applies to some generations. At Easter 1943 the Warsaw Ghetto went up in flames. My mother wrote in her memoirs:

On Good Friday, as the Ghetto was on fire and people were dying horrific deaths right next to us, Kalka and I went to visit the Tombs in the Old Town. It was a custom that became firmly established during the occupation: patriotically decorated graves were a way of fighting the Germans. But I remember a feeling that overcame me at the sight of that festive, pious crowd. The weather was lovely, so warm that I was wearing only a skirt and a blouse (‘a new one,’ meaning recently altered, pink). Burnt scraps of paper with rows of widely splayed out, indecipherable characters floated through the air towards the Old Town, disturbing the usual peace of the Holy Day. Perhaps Miłosz should have used this landscape of the Old Town at Easter as the backdrop to his poem . . .

Later, in 1945, in the labour camp at Wüstegiersdorf (present-day Głuszyce), this is what my mother’s Easter was like:

I think it was on Good Friday that a horse broke a leg inside the perimeter of the camp, and before the Germans arrived to collect it—it was gone. We managed to grab hold of (the part with the hoof) of the quartered horse. [. . .] I see that holiday as being about the miracle of death rather than of resurrection.

Doesn’t that put our dilemmas over face masks into perspective?

Easter Saturday, April 12

Self-isolation is the experience of old age avant la lettre. We begin to comprehend what it means to have the space available for walking reduced to our immediate vicinity. A view has become precious beyond words. A bag of gold for a balcony, a small terrace, a window looking out upon green foliage!

We attach extraordinary importance to exchanging greetings with rarely seen neighbours. We spy on nature that we were unaware of before. If we could spare some bread, we would feed the pigeons on our windowsill. But even without any bread we are beginning to recognize individual birds that strut up and down the ledge beneath our window.

When the world goes back to ‘normal,’ how quickly will we regain middle age?

The Earth, meanwhile, has been catching its breath . . . T., ever the idealist, hopes that when this is over, people will have changed: they will no longer own so many cars, won’t fly to places they don’t need to, not least because air tickets will be incredibly expensive. But economists predict the opposite. Airlines—in an attempt to tempt back impoverished customers—will lower their prices substantially.

Our conversations increasingly resemble the exchanges of identical sentences in Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie. Like his characters, we are ensnared in a situation from which there is, for the moment, no escape. On the other hand, the more monotonous the days, the more eventful have been the nights. Dreams have grown longer to fill the time available for erotic adventures.

Last night I had an affair with Greta Garbo. Discretion doesn’t allow me to share the details. Especially as I hope there will be a sequel.

Monday, May 11

Literary associations of the ‘here and now’ lead obviously to Sartre’s No Exit. An increasing number of people are learning that ‘hell is other people.’ Through the windows, parched for a whiff of spring, screaming matches filter in.

I read Huysmans’s Against Nature (1884). It is a fitting title for our topsy-turvy world with animals walking in the streets and people spying on them through the windows. But who is to say what is against nature? The main and only protagonist of this decadent novel, the Duc des Esseintes—an aesthete, a dandy, eccentric, erudite and a misanthrope—has some useful advice for us. Someone like him would be at ease in the current situation. He had to incur considerable expense in order to achieve his ideal of self-isolation. However, being someone who couldn’t stand people and noise, he had little choice.

The main thing is to know how to [. . .] substitute the vision of a reality for the reality itself [3]. Not a bad piece of advice! Or: Travel, indeed, struck him as being a waste of time, since he believed that the imagination could provide a more-than-adequate substitute for the vulgar reality of actual experience. Because recalling a trip or planning it is often more exciting than the exertions of travel.

Having decided to visit London, the Duc packs his bags and issues instructions to his servants on what to do during his prolonged absence, but he doesn’t get further than a Paris bookshop where he peruses travel guides, and a tavern near the station. There he eats and drinks until he is seized by an overwhelming reluctance to a change in location: What was the good of moving, when a fellow could travel so magnificently sitting in a chair?

Des Esseintes is a figure tailor-made for our times. He lived mainly at night (like many of us). He observed the rhythm of a sanatorium: every activity had its allocated time (this what we do too, willy-nilly). He had his house remodelled in an eccentric fashion (it’s true that we can’t afford to build a ship’s cabin in our dining room, but we have nevertheless made some daring changes to our modest quarters). He relished looking at photographs of a beach-side casino, reading guidebooks, studying train fares and timetables (how often do we return to our holiday photos?) He employed ingenious tricks to feel as if he were at the seaside: in his hallway he assembled a small pile of fishing rods, nets, sails and an anchor made of cork. He added sodium sulphate to his bath water and whipped up waves reminiscent of a swaying boat, and sniffed ropes and lines bought specially for this purpose from a ropery that smelled of the port.

He attached the utmost importance to his appearance. Dandies, both male and female, dress up for themselves, not for applause. We should bear this in mind as we read Huysmans dressed in pyjamas that we’ve put on inside out.

His faith in the imagination has been adopted by the surrealists. And also by Mac Orlan, whose ‘passive adventurers’ drew sustenance from the exploits of the active ones. I wish our sitting at home proved to be as fruitful!

Saturday, May 16

In his book Swimming to Cambodia, Spalding Gray, the American actor, writer, author of monologues, chronicler of life, neurotic, and stand-up comedian, describes a visit to his therapist. Their roles are suddenly reversed as the therapist starts to recount his dramatic wartime experiences. Having listened to him, the bewildered patient mumbles that this kind of experience must have reconfigured the latter’s view of the world. To which the therapist responds:

No. Uh-uh. Nothing changes, no. We thought that, you see. In the first reunions of the camps everyone was swinging, like a big sex club with the swinging and the drinking and the carrying on as though you die tomorrow. Everyone did what they wanted. The next time, not so much, not so much. The couples stayed together. The next time, we were talking about whether or not we could afford a summer home that year. Now when we meet, years later, people talk about whether or not radioactive smoke-detectors are dangerous in suburban homes. Nothing changes.

Toutes proportions gardées, of course, but I was reminded of this excerpt when hearing predictions of how profoundly we will be changed by this experience.

Sunday, June 7

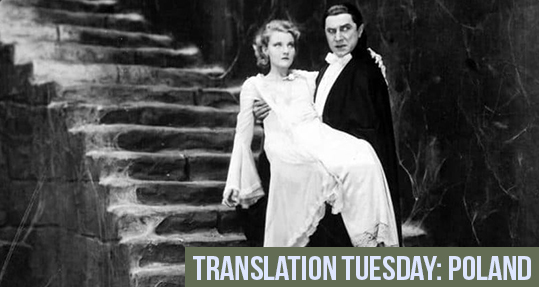

I’ve gone back to Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1897). I’ve discussed this classic with my students as part of a course on the representation of women in art and literature at the turn of the century. When the beautiful Lucy Westenra is infected with vampirism, she is instantly transformed from an angelic bride-to-be into a bloodthirsty femme fatale.

However, the times we live in shape our perspective, and so nowadays I read this story primarily as an allegory of infection. Infections, like vampires, never die completely. In both cases bats tend to be the connecting link.

In a premonition of the attack that might infect her, what the extremely sensitive Lucy describes in her diary resembles nothing less than being surrounded by viruses:

The air seems full of specks, floating and circling in the draught from the window, and the lights burn blue and dim. What am I to do? God shield me from hard this night!

In addressing the next victim, the doctor and expert on the occult, professor van Helsing, does not hesitate to use the key word:

He have infect you—oh forgive me, my dear, that I must say such; but it is for good of you that I speak. He infect you in such wise, that even if he do no more, you have only to live—to live in your own old, sweet way; and so in time, death, which is of man’s common lot and with God’s sanction, shall make you like to him.

Just like the plagues depicted by other writers in less symbolic ways, this one, too, has been imported from the ‘wild’ and superstitious East into the ‘civilized’ West. Like them, it arrives by boat.

Dracula’s appearance on a merchant ship echoes the cholera epidemic of 1831, which was brought to England from the Baltics by sailors spreading the disease from port to port. Since that time the spectre of cholera—and also of syphilis and rabies—had been part of the everyday reality of Victorian society. As in the medieval dance of death, the poor and the rich were united in their fear of the disease.

Friday, June 26

Since the start of the pandemic, M. and I have done our shopping online. It actually saves a lot of time. But of course, accidents can happen. P. has only now just started to master the intricate ways of the virtual world. The numerals one and seven look similar, so she has just bought seven heads of cauliflower instead of one. But she need not worry. First, seven is a magic number. Second, she is lucky not to have ordered seven pork chops by mistake! What would a vegetarian do with pork chops? Third, cauliflower can be marinated and preserved. And four, seven cauliflowers accidentally bought at the height of the pandemic sounds like the beginning of a Márquez novel. It’s just that in the absence of the Master someone needs to write it.

Saturday, June 27

Today the global number of infections and deaths stands at so and so many . . . More than yesterday and considerably more than a week ago. However, people have gotten accustomed to the evil lurking around the corner. Those who spent three months hunkering down at home, go out into the streets without face masks. Maybe, before setting out, they practice some sorcery they’ve learned while in hiding?

A few people keep waiting. Those who still are, seem to do so less intensely. E la nave va. The ship of fools sails into the open sea.

[1] Trans. John E. Woods; [2] trans. Edith Grossman; [3] trans. Robert Baldick

Translated from the Polish by Julia Sherwood and Peter Sherwood

Agnieszka Taborska is a writer, art historian, and translator (of Philippe Soupault, Gisele Prassinos, Roland Topor and Spalding Gray). Since 1988 she has divided her time between Warsaw and Providence, R.I., where she lectures on literature and art history at the Rhode Island School. She is the author of collections of short stories (Not as in Paradise and The Whale, or Objective Chance); literary mystifications (The Dreaming Life of Leonora de la Cruz and The Unfinished Life of Phoebe Hicks); Topor’s Alphabet; Conspirators of Imagination. Surrealism; reportages from travels (American Crumbs, Surrealist Paris, Brittany, Providence) and many children books. Her books have been translated into English, French, German, Spanish, Korean, and Japanese.

Julia Sherwood was born and grew up in Bratislava, Slovakia. Since 2008 she has been working as a freelance translator of fiction and non-fiction from Slovak, Czech, Polish, German, and Russian. She is based in London and is Asymptote’s editor-at-large for Slovakia.

Peter Sherwood is an academic who, until his retirement in 2014, taught in universities in the UK and the USA. He translates fiction and poetry, and occasionally non-fiction, from Hungarian and (with his wife Julia Sherwood) from Slovak and Czech. He is based in London.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: