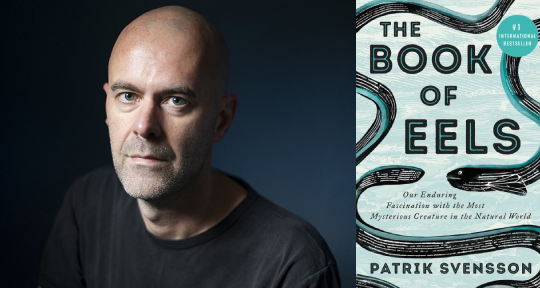

The Book of Eels by Patrik Svensson, translated from the Swedish by Agnes Broomé, HarperCollins, 2020

The full English title of Swedish arts and culture journalist Patrik Svensson’s debut book is spot on: The Book of Eels: Our Enduring Fascination with the Most Mysterious Creature in the Natural World. The original Swedish subtitle lacks “Our Enduring Fascination” and simply states “The Story of the Most Mysterious Creature in the World.” I like the English title better, because it’s that detail, the fact that the book is not just about eels, but also about us humans, our interest in the eels, and why they should matter to us, that makes this book about a slimy, snake-like water-creature relevant.

Maybe you don’t think that you could be interested in a full-length book about every conceivable fact about eels. I certainly didn’t know I could be that interested until the buzz hit the Swedish literary scene last fall. It wasn’t just the book reviews, the author interviews, or the literary podcasts that kept turning their attention to The Book of Eels—Svensson was also awarded the August Prize, Sweden’s most prestigious literary award. And it didn’t stop there; even before the year ended, The Book of Eels had been sold to over thirty other countries. When I first heard about The Book of Eels, I could see why it stirred interest, because the subject matter is unconventional. So, what is the buzz all about? Well, for being a book about scientific, historic, and philosophical facts, it’s put together and presented in a prose that is easy to follow, even if you don’t typically read about the science of the bottom of the ocean or the ancient Greek origin of the scientific method. This is how Svensson depicts the Sargasso Sea:

The water is deep blue and clear, in places very nearly 23,000 feet deep, and the surface is carpeted with vast fields of sticky brown algae called Sargassum, which give the sea its name. Drifts of seaweed many thousands of feet across blanket the surface, providing nourishment and shelter for myriad creatures: tiny invertebrates, fish and jellyfish, turtles, shrimp, and crabs. Farther down in the deep, other kinds of seaweed and plants thrive. Life teems in the dark, like a nocturnal forest.

And so, with that nocturnal forest, Svensson establishes the centre stage for the Anguilla anguilla, the European eel, while simultaneously teaching us about the natural world and drawing us into his narrative.

The excellent translation into English by Agnes Broomé, professor in Scandinavian languages at Harvard with a Ph.D. in Translation Studies from UCL, stays close to the Swedish original, though it makes minor deviations to keep the steady tone, rhythm, and accessible fluency without forcing the shorter Swedish sentence structure into the English translation. It is reasonable to suspect that a book depicting local, southern Swedish fishing traditions would need additional explanations or footnotes in order to be completely understandable for an international reader. However, the traditions of eel fishing and the specifics of, for example, Hanö Bay, are so local and distinct, that even the general Swedish readership requires these explanations. This has therefore not posed extra challenges to the translation, and the English version is able to follow the Swedish original in these instances:

The oldest eel sheds are from the eighteenth century. There were at least a hundred along this thirty-mile stretch of coast once, and fifty or so are still standing. They are typically named after the fishermen who used them or the myths and legends said to have taken place in them. They’re called things like the Brothers’ Shed, Jeppa’s Shed, Nils’ Shed, the Hansa Shed, the Twin Shed, the King’s Shed, the Smuggler’s Shed, the Tail Shed, the Cuckoo Shed, and the Perjurer’s Shed. Some of the sheds are derelict, some have been converted into seaside summer cottages, but a handful are still used for their original purpose. It’s in these sheds you find a second category of people, quite distinct from the natural scientists, who have historically had a close relationship with the eel: the fishermen.

The book’s eighteen chapters alternate between fact-dense yet delightfully narrated essayistic information about the European eel and the history of the science that surrounds it, with autobiographical sequences about Svensson’s childhood and his relation to his father, who teaches him eel fishing. Thus, the book is a combined memoir and essay collection.

One of the most entertaining of the essayistic chapters covers the experience of a young Sigmund Freud in Italian Trieste, in the hunt to discover—can you guess?—the reproductive organs of the eels:

Nineteen-year-old Freud was an ambitious young scientist. He’d gone to Trieste to write a groundbreaking report that answered, once and for all, the question that had confounded science for centuries: How do eels reproduce? He probably learned a great deal about the importance of patient and systematic observation in research, knowledge he would later apply to his patients on the therapy couch.

Freud’s scientific endeavour in Trieste was a failure, in spite of the amounts of eels he dissected during his months there. A frustration that led to a future interest—and better success—for the young Freud, per chance? A book about eels can cover more aspects of human history than you’d think.

Other parts of the book zoom in on Aristotle’s thoughts on the origin of eels—a puzzle that forced him to deviate from his own practice of the principle that all knowledge must be based in experience. The mysterious eel simply wouldn’t have its reproductive business being observed. It would take more than 2,000 years and an assiduous Danish scientist named Johannes Schmidt who spent twenty years, including a world war, looking for baby eels in a vast sea to determine the place where the eels are born: the Sargasso Sea.

These essayistic chapters with historical and scientific facts are nicely framed by the story about Svensson and his father:

My father liked eel fishing for several reasons. I don’t know which was the most important . . . The stream represented his roots, everything familiar he always returned to. But the eels moving through its depths, occasionally revealing themselves to us, represented something else entirely. They were, if anything, a reminder of how little a person can really know, about eels or other people, about where you come from and where you’re going.

This isn’t just a well-written nonfiction book about a mysterious animal—it’s also a sensitive and moving memoir about the narrator and his father. Two men, one young (at least during the majority of the book) and one adult, who lack a shared language for talking about feelings and what they mean to each other, but who nevertheless have this together, the tradition of fishing for eels.

The way the book introduces us to eel fishing with the two men, down at the creek near their house, gives the impression of a tradition carried down through generations. Later in the book, however, we discover along with Svensson that it’s more likely that this tradition was initiated by Svensson’s father. Maybe he wanted a hobby. Maybe he liked being out in nature, by the water. Maybe he was just fascinated by the eels—this far into the book, we already know how fascinating eels really are. Maybe it was all of these things combined that made Svensson’s dad pick up eel fishing. And maybe it was also a way to create a family tradition that connected him with his son, an activity that gave them time and memories together.

The narration starts off with a basic orientation about the eels, what they are, what we know about them, and the things we don’t know about them. In spite of extensive research, no one has yet been able to observe the birth of an eel. Which, according to the basic rules of science that we like to think that we adhere to, means that we don’t know where or how eels are born. It’s still a mystery—we can only guess. In the beginning, reading about an animal with a slippery skin and a movement pattern that make the reptile part of my brain tell the rest of me to cringe, I felt disgusted. But I thought that halfway through or so I’d be over it and not care so much. However, even on page 250, I continued to read with the same disgusted reaction to the eels. Nevertheless—and more interestingly—even though I cringed for 250 pages, it was worth it. It doesn’t make the eels any less fascinating, and it certainly doesn’t decimate Svensson’s depiction of a loving father who sometimes doesn’t know how to verbalize his need to connect with his son. Turning eels into an interesting read may seem challenging to some, but it’s exactly what Svensson accomplishes.

One of the chapters towards the end, “The Long Journey Home,” describes the incredible journey that eels make back to the Sargasso Sea in order to—we assume—reproduce. In fact, the whole book is about the origin and home of the eels, how they figure out how to get back there, and the mystery of why, once back, they’re never seen again, neither in that place nor anywhere else. It’s also a book about how a son and his father connect and how humans fit together amid disrupted lineages. And, importantly, it’s a book about an animal on the verge of extinction and how that will affect us—because even if we’re different kinds of creatures, in the end, we’re all dependants of the same system.

Eva Wissting holds a BA (Hons) in English Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Toronto. She is Asymptote’s Editor-at-Large for Sweden.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: